You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Our FDNY Company Assignments - Proby Class 1985

- Thread starter jbendick

- Start date

William Carberry

Bill was a retired member of the New York City Fire Department and the Holy Name Society and Emerald Society of the FDNY. He was an honorary member of the Dikeman Engine and Hose Co., Goshen, NY, and a U.S. Army Veteran and member of the American Legion. Shortly after returning from Ft. Lewis in Washington, Bill became a firefighter with 27 Truck, FDNY in the Bronx, where he forged many wonderful friendships lasting until his final days. With the ending of a long and proud career with the FDNY,

Bill was a retired member of the New York City Fire Department and the Holy Name Society and Emerald Society of the FDNY. He was an honorary member of the Dikeman Engine and Hose Co., Goshen, NY, and a U.S. Army Veteran and member of the American Legion. Shortly after returning from Ft. Lewis in Washington, Bill became a firefighter with 27 Truck, FDNY in the Bronx, where he forged many wonderful friendships lasting until his final days. With the ending of a long and proud career with the FDNY,

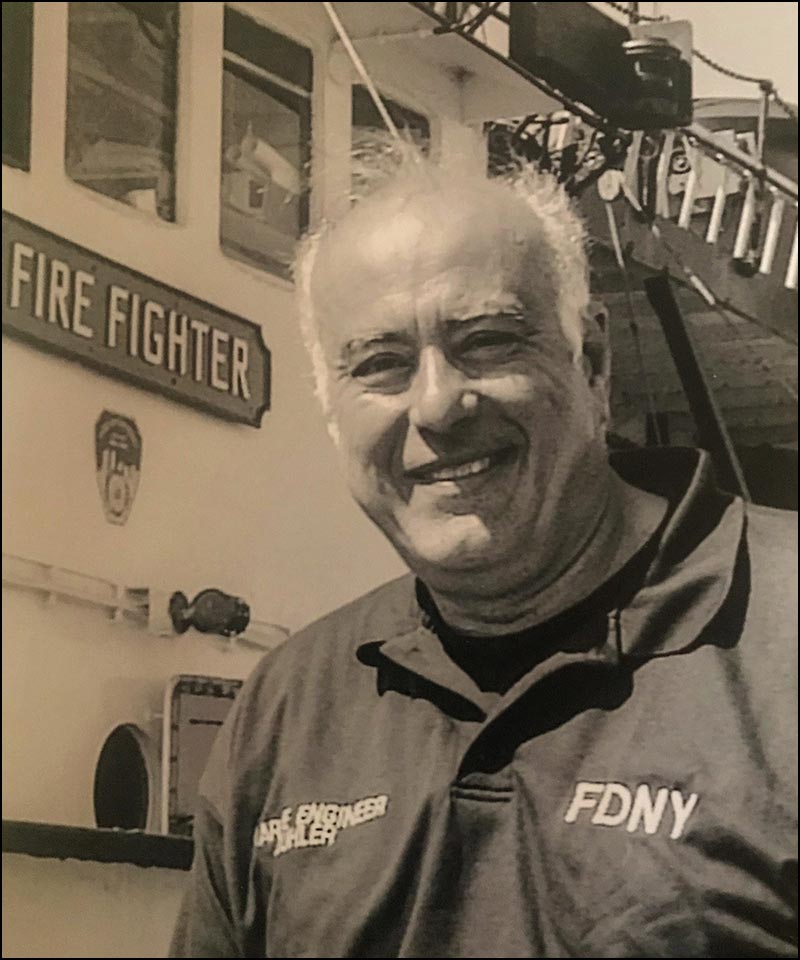

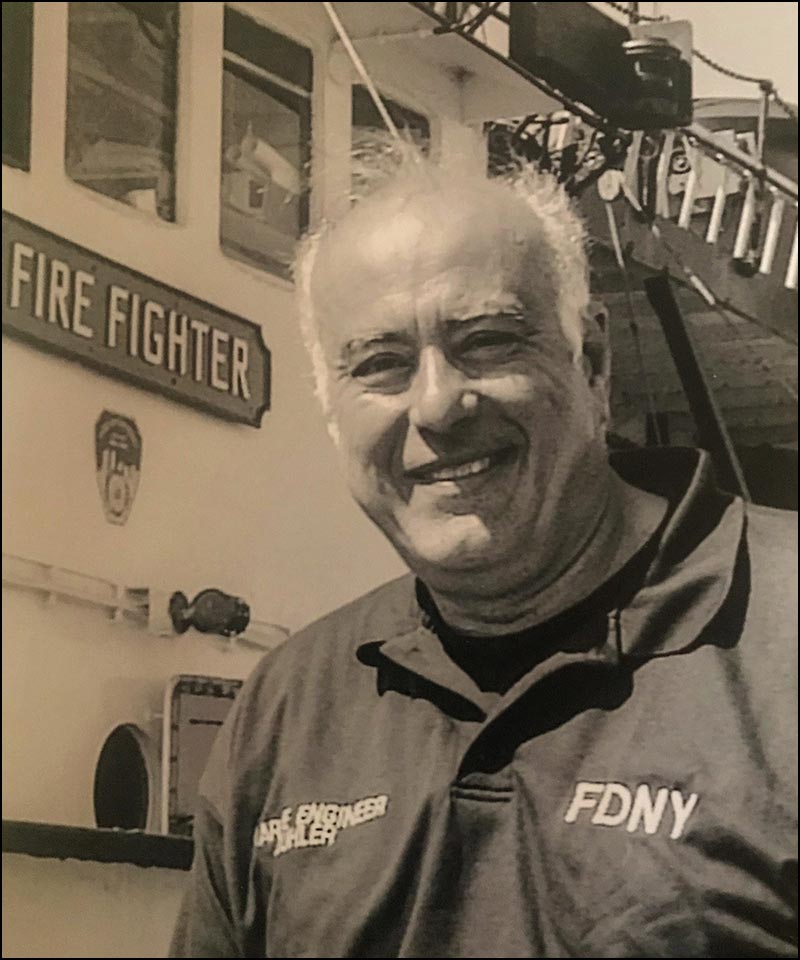

John Buhler - died from WTC ilnesss

www.firehero.org

www.firehero.org

John L. Buhler - National Fallen Firefighters Foundation

John Buhler of Floral Park, New York, was a husband, father, friend, and mentor to those who were privileged to know him. Following the attacks on the

www.firehero.org

www.firehero.org

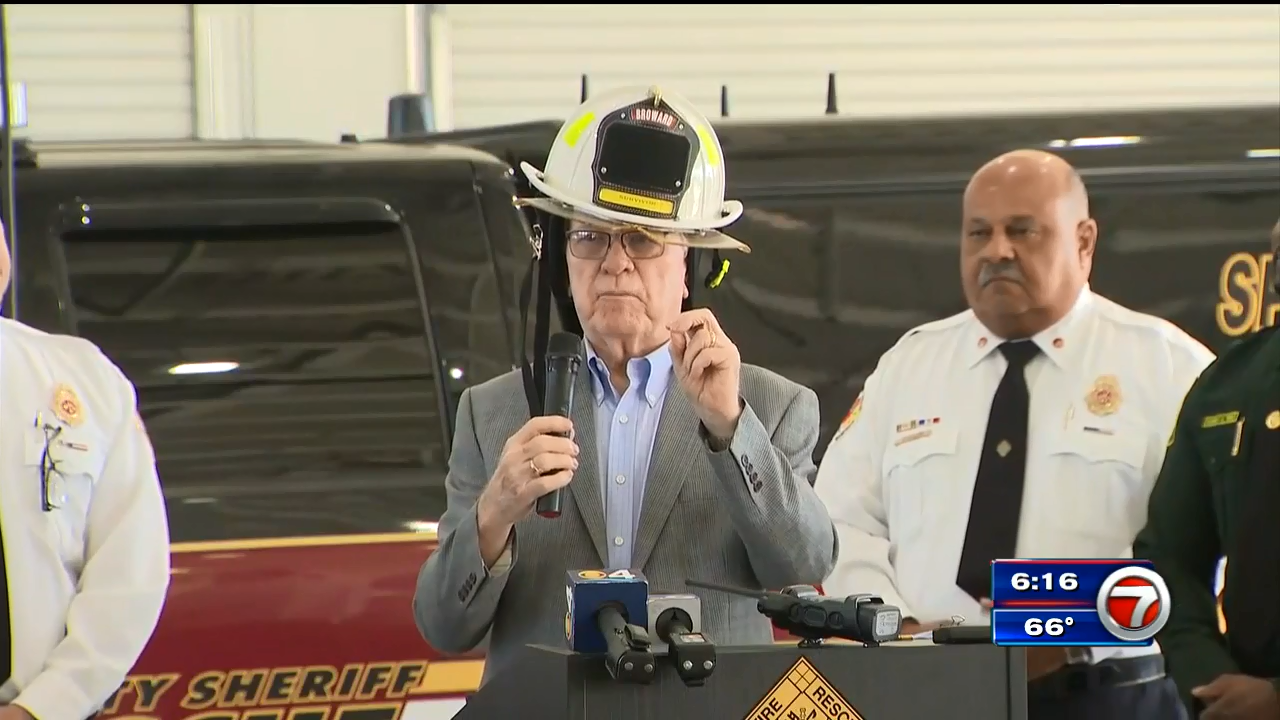

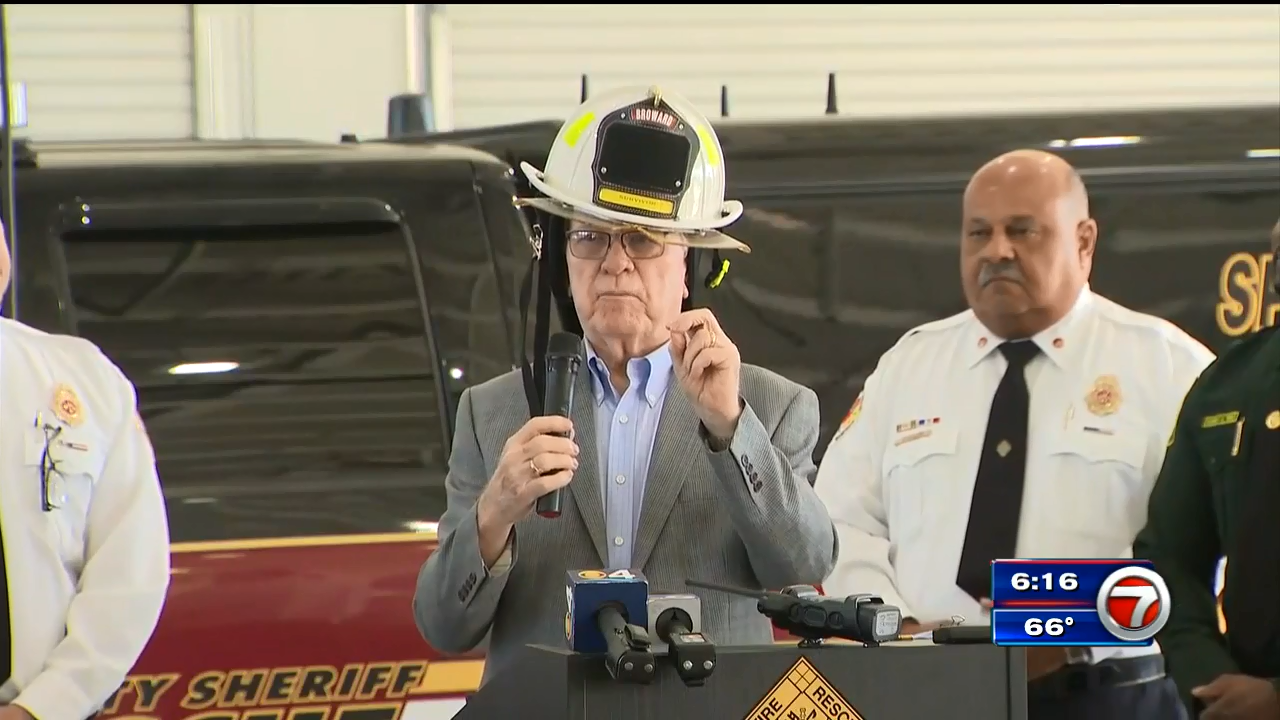

Bernard Casey

Deputy Chief Fire Marshal

wsvn.com

wsvn.com

Deputy Chief Fire Marshal

Retired firefighter reunites with rescuers after heart attack - WSVN 7News | Miami News, Weather, Sports | Fort Lauderdale

HALLANDALE BEACH, FLA. (WSVN) - Retired New York firefighter Bernard Casey was made an honorary member of Broward Sheriff Fire Rescue on Friday.Casey suffered a<a class="excerpt-read-more"...

wsvn.com

wsvn.com

John Malast

Supervising Fire Marshal

Jan. 29, 1989

The New York Times Archives

Rupert Callender leaned over a small table in his makeshift trailer home, explaining to a visiting fire marshal why he thought his 8-year-old son Danny had burned down their ramshackle house in Little Neck, Queens, last month.

A few feet away, another marshal sat on a couch listening to Danny describe the nightmares he has about the fire, which nearly killed his father. As they searched for clues about Danny's behavior, the marshals seemed more like psychiatrists than firefighters.

And in some ways they are. That is because the two, Thomas J. Williams and John Malast, are not typical fire marshals. As members of the New York City Fire Department's Juvenile Firesetters Intervention Program, they are trained to deal with young arsonists.

The program, begun in November 1986 in the Bronx, offers young arsonists up to age 11 an alternative to arrest. After it is determined that a child has started a fire, the family is interviewed and evaluated by a pair of marshals. If necessary, they refer the child to community agencies for counseling or psychiatric care. Misses His Mother

The New York program is one of several that have been organized nationwide in response to a steady increase in the number of juvenile arsonists. While it has no precise figures, the National Fire Protection Association, a private 40,000-member group, estimates that children between the ages of 7 and 18 accounted for 40 percent of arson arrests in the United States last year.

Shortly after arriving at the Callender home, the fire marshals learned that Danny has been unhappy since his mother Audrey, who has been separated from Mr. Callender for six years, moved to Puerto Rico last summer. Danny was especially depressed that she did not come home for Christmas.

''He misses her very much,'' said Mr. Callender, a postal worker who suffers from diabetes and asthma.

Danny's unhappiness almost led to disaster on Dec. 29. He was alone in his room at 10 P.M., playing with his mother's cigarette lighter - one of the few objects she had left behind - when suddenly the top floor of the house went up in flames. Deaths Were an Inspiration

''The lighter reminded me of my mother,'' Danny told the marshals as he described how he had rolled the lighter on his rug and started the fire. He escaped along with his father; a 13-year-old brother, John, and a boarder. Mr. Callender's head was severely burned.

Since the program began, 353 children have been interviewed. Only three have set fires since meeting with the marshals, said James D. McSwigin, who is the program's founder and director.

''We may not be able to stop the first fire, but we're very successful in stopping the second,'' he said.

Sign up for the New York Today Newsletter Each morning, get the latest on New York businesses, arts, sports, dining, style and more. Get it sent to your inbox.

Mr. McSwigin is no stranger to juvenile arson. When he became a New York City fire marshal in 1978, his first arrest was of a 12-year-old boy who had set a Bronx apartment building ablaze. The boy hanged himself hours after he was arraigned and released.

''That made me realize that there must be a better way to deal with these young kids than to just arrest them,'' said Mr. McSwigin, who is 49 years old and whose own brother, sister-in-law and two of their children were killed in a fire on Long Island two years ago.

But it was the death of a fellow firefighter, Capt. James F. McDonnell, in a Bronx blaze started by a 4-year-old boy in 1985 that prompted Mr. McSwigin to start the program. 'Old-Fashioned Outreach'

Shortly after the program was approved, staff psychologists at Bellevue Hospital Center pored over applications from more than 70 fire marshals.

The 18 men selected work in shifts around the clock in the Bronx as well as in Queens, where an office was opened in October.

''In a weird sense, what they're doing is old-fashioned outreach,'' said Arnold Korotkin, who has worked closely with the program as Bronx coordinator for the New York City Department of Mental Health. ''A lot of these children are from single-parent families, and the marshals come in as father figures who get the parents and kids to bring out all sorts of problems and concerns.''

Some children set fires simply out of curiosity, while others use them to gain attention, experts said. Marshals in the New York program have found that the most abused and desparate children often set fires as a cry for help.

Despite the program's success, it may be jeopardized if the Fire Department's budget is cut. Fiscal Problems

Mr. McSwigin said he has been told by his superiors that the program, which costs about $600,000, will be on the chopping block in February when Mayor Edward I. Koch announces his proposed budget for New York City.

But the Fire Commissioner, Joseph F. Bruno, said the entire program will not be discontinued even if there are severe cutbacks in the department's budget.

''We won't know what will ultimately happen to the program until the Mayor announces his budget,'' Mr. Bruno said. ''It all depends on how deep the budget cuts must be.''

During their visits with families in the program, one marshal interviews the parents while the other shows the child a series of photographs of a fire's consequences. The first pictures depict objects like a burning candle and are followed by more grim photographs of a scorched teddy bear and a charred 10-year-old boy. The marshals and the parents then discuss counseling for the child. The marshals' work usually ends once they leave the home.

In Danny Callender's case, the two marshals recommended psychiatric therapy. Mr. Callender welcomed the suggestion. And as the marshals prepared to leave his trailer, he began to reflect on brighter prospects.

''I can always replace the house,'' he said. ''But I can never replace Daniel.''

Supervising Fire Marshal

A Fire Unit Counsels Troubled Young Arsonists

Jan. 29, 1989

The New York Times Archives

Rupert Callender leaned over a small table in his makeshift trailer home, explaining to a visiting fire marshal why he thought his 8-year-old son Danny had burned down their ramshackle house in Little Neck, Queens, last month.

A few feet away, another marshal sat on a couch listening to Danny describe the nightmares he has about the fire, which nearly killed his father. As they searched for clues about Danny's behavior, the marshals seemed more like psychiatrists than firefighters.

And in some ways they are. That is because the two, Thomas J. Williams and John Malast, are not typical fire marshals. As members of the New York City Fire Department's Juvenile Firesetters Intervention Program, they are trained to deal with young arsonists.

The program, begun in November 1986 in the Bronx, offers young arsonists up to age 11 an alternative to arrest. After it is determined that a child has started a fire, the family is interviewed and evaluated by a pair of marshals. If necessary, they refer the child to community agencies for counseling or psychiatric care. Misses His Mother

The New York program is one of several that have been organized nationwide in response to a steady increase in the number of juvenile arsonists. While it has no precise figures, the National Fire Protection Association, a private 40,000-member group, estimates that children between the ages of 7 and 18 accounted for 40 percent of arson arrests in the United States last year.

Shortly after arriving at the Callender home, the fire marshals learned that Danny has been unhappy since his mother Audrey, who has been separated from Mr. Callender for six years, moved to Puerto Rico last summer. Danny was especially depressed that she did not come home for Christmas.

''He misses her very much,'' said Mr. Callender, a postal worker who suffers from diabetes and asthma.

Danny's unhappiness almost led to disaster on Dec. 29. He was alone in his room at 10 P.M., playing with his mother's cigarette lighter - one of the few objects she had left behind - when suddenly the top floor of the house went up in flames. Deaths Were an Inspiration

''The lighter reminded me of my mother,'' Danny told the marshals as he described how he had rolled the lighter on his rug and started the fire. He escaped along with his father; a 13-year-old brother, John, and a boarder. Mr. Callender's head was severely burned.

Since the program began, 353 children have been interviewed. Only three have set fires since meeting with the marshals, said James D. McSwigin, who is the program's founder and director.''We may not be able to stop the first fire, but we're very successful in stopping the second,'' he said.

Sign up for the New York Today Newsletter Each morning, get the latest on New York businesses, arts, sports, dining, style and more. Get it sent to your inbox.

Mr. McSwigin is no stranger to juvenile arson. When he became a New York City fire marshal in 1978, his first arrest was of a 12-year-old boy who had set a Bronx apartment building ablaze. The boy hanged himself hours after he was arraigned and released.

''That made me realize that there must be a better way to deal with these young kids than to just arrest them,'' said Mr. McSwigin, who is 49 years old and whose own brother, sister-in-law and two of their children were killed in a fire on Long Island two years ago.

But it was the death of a fellow firefighter, Capt. James F. McDonnell, in a Bronx blaze started by a 4-year-old boy in 1985 that prompted Mr. McSwigin to start the program. 'Old-Fashioned Outreach'

Shortly after the program was approved, staff psychologists at Bellevue Hospital Center pored over applications from more than 70 fire marshals.

The 18 men selected work in shifts around the clock in the Bronx as well as in Queens, where an office was opened in October.

''In a weird sense, what they're doing is old-fashioned outreach,'' said Arnold Korotkin, who has worked closely with the program as Bronx coordinator for the New York City Department of Mental Health. ''A lot of these children are from single-parent families, and the marshals come in as father figures who get the parents and kids to bring out all sorts of problems and concerns.''

Some children set fires simply out of curiosity, while others use them to gain attention, experts said. Marshals in the New York program have found that the most abused and desparate children often set fires as a cry for help.

Despite the program's success, it may be jeopardized if the Fire Department's budget is cut. Fiscal Problems

Mr. McSwigin said he has been told by his superiors that the program, which costs about $600,000, will be on the chopping block in February when Mayor Edward I. Koch announces his proposed budget for New York City.

But the Fire Commissioner, Joseph F. Bruno, said the entire program will not be discontinued even if there are severe cutbacks in the department's budget.

''We won't know what will ultimately happen to the program until the Mayor announces his budget,'' Mr. Bruno said. ''It all depends on how deep the budget cuts must be.''

During their visits with families in the program, one marshal interviews the parents while the other shows the child a series of photographs of a fire's consequences. The first pictures depict objects like a burning candle and are followed by more grim photographs of a scorched teddy bear and a charred 10-year-old boy. The marshals and the parents then discuss counseling for the child. The marshals' work usually ends once they leave the home.

In Danny Callender's case, the two marshals recommended psychiatric therapy. Mr. Callender welcomed the suggestion. And as the marshals prepared to leave his trailer, he began to reflect on brighter prospects.

''I can always replace the house,'' he said. ''But I can never replace Daniel.''

Attachments

Last edited:

Gregory Hoover US Navy, FDNY

Mr. Hoover served with the US Navy aboard the USS La Salle for which he was a plank owner from 1962-68. He earned a BA from Richmond College of CUNY and a Juris Doctor from New York Law School. He was an attorney for 41 years, most recently with Gregory G. Hoover, Sr. PC law firm in Warwick. He was a retired Lieutenant with the NYC Fire Department. He retired out of Engine 75, Ladder 33, Battalion 19.

Mr. Hoover served with the US Navy aboard the USS La Salle for which he was a plank owner from 1962-68. He earned a BA from Richmond College of CUNY and a Juris Doctor from New York Law School. He was an attorney for 41 years, most recently with Gregory G. Hoover, Sr. PC law firm in Warwick. He was a retired Lieutenant with the NYC Fire Department. He retired out of Engine 75, Ladder 33, Battalion 19.

Last edited:

Roger Steinert NYPD, FDNY

Attended Brooklyn Tech High School, Staten Island Community College followed by John Jay College of Police Science. He began his career working for the city of New York in1964 as a police officer and later as a NYC Fireman, primarily stationed on Staten Island at Ladder Company 86, working 25 years before retiring in 1995.

Attended Brooklyn Tech High School, Staten Island Community College followed by John Jay College of Police Science. He began his career working for the city of New York in1964 as a police officer and later as a NYC Fireman, primarily stationed on Staten Island at Ladder Company 86, working 25 years before retiring in 1995.

Congratulations and thank you to the 250 probationary firefighters who began their careers October 26, 1968, risked their lives repeatedly and performed their duties heroically. Only a few are noted above, but all were heroes the minute they raised their hands and became firefighters. Well done to the many chiefs, officers, fire marshals and firefighters of this class who distinguished themselves with selfless service and dedicated performance of duty. RIP to those who have passed away. Never forget.

Congratulations and thank you to the 250 probationary firefighters who began their careers October 26, 1968, risked their lives repeatedly and performed their duties heroically. Only a few are noted above, but all were heroes the minute they raised their hands and became firefighters. Well done to the many chiefs, officers, fire marshals and firefighters of this class who distinguished themselves with selfless service and dedicated performance of duty. RIP to those who have passed away. Never forget.

I want to give a Big thank you Mack, for all your input to the class of 9/14/68 and everyone else who acknowledged our class. Thank you brothers! May I give a shoutout to the ones I worked with, Harry Myers, Sal DeVito, and Clem Lagerman. Dan, thanks for the nice words about me and to you Willy also. Dennis O. den114 a hello to you, it been a while since we got promoted.

I’m blessed to be associated with a great many firefighters from the class of 9/14/68. Be well brothers as well as everyone else in this great site. Join Bendick and Chief JK, I’m glad to be one of your brothers.

I’m blessed to be associated with a great many firefighters from the class of 9/14/68. Be well brothers as well as everyone else in this great site. Join Bendick and Chief JK, I’m glad to be one of your brothers.

- Joined

- May 6, 2010

- Messages

- 16,225

^^^^^ Very well said Tom.....a Thank You to all who jumped in with comments ...wishes & likes.......also a special Thank You to John for kicking this thread off & certainly a BIG THANK YOU to mack who went into overdrive posting info.....as I said earlier with 250 in the class I did not ever get to know everyone personally but mack sure found & posted some great info that paints a background of so many.

Chief - Every member of your proby class has a story - a career with experiences, faces, risks, dangers, humor, injuries - that can only be matched by soldiers in combat. Selfless service. Teamwork. Hard work. Fear. Bravery. Trust. Love for others. Too bad we can't capture every member's story.^^^^^ Very well said Tom.....a Thank You to all who jumped in with comments ...wishes & likes.......also a special Thank You to John for kicking this thread off & certainly a BIG THANK YOU to mack who went into overdrive posting info.....as I said earlier with 250 in the class I did not ever get to know everyone personally but mack sure found & posted some great info that paints a background of so many.

- Joined

- May 6, 2010

- Messages

- 16,225

FDNY R&W 1968 - indicates how busy units were when class graduated from the Fire Academy. Units all over the city had significantly increased activity. Second sections, new units, new battalions, new division, company interchange, Adaptive Response, DRBs, new apparatus, tower ladders - this class experienced many efforts to combat the War Years' countless fires, MFAs, ADVs, emergencies.

- Joined

- May 6, 2010

- Messages

- 16,225

10-26-68.....PROBY SCHOOL GRADUATION (CLASS # 1985 ) 56 YRS AGO....4 Great History Pages. .(Compiled 2 yrs ago )....

www.nycfire.net

www.nycfire.net

Our FDNY Company Assignments - Proby Class 1985

54 years ago today we were released from proby school to go to our assigned companies. Mine was Engine 96. This class included myself, Jack Kleehaas, and Tom Kuefner along with over 240 others.

www.nycfire.net

www.nycfire.net

What a great ride we had, right guys. Thanks for the memories10-26-68.....PROBY SCHOOL GRADUATION (CLASS # 1985 ) 56 YRS AGO....4 Great History Pages. .(Compiled 2 yrs ago )....

Our FDNY Company Assignments - Proby Class 1985

54 years ago today we were released from proby school to go to our assigned companies. Mine was Engine 96. This class included myself, Jack Kleehaas, and Tom Kuefner along with over 240 others.www.nycfire.net