You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

80th Anniversary of Cocoanut Grove Fire - 492 Killed

- Thread starter Capttomo

- Start date

- Joined

- Jun 27, 2007

- Messages

- 3,736

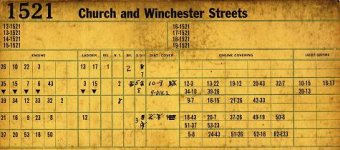

And if Boston College had won their football game against rival Holy Cross the death total would have been higher, BC players and fans cancelled plans for a victory celebration. At 10:20 PM Box 1521 was pulled for an automobile fire and was transmitted. This was in an area when you got a heavy first alarm response Engines 7-10-22-and 35 along with Ladders 13, 17 and the Rescue. As companies worked on the car fire they were notified by a passer-by of a fire at the Grove and they quickly responded where they find people trapped inside. Second alarm was skipped followed by a third @ 10:23, fourth at 10:25 and the fifth @ 11:02. In the wake of this disaster numerous safety features including outward only opening doors next to the revolving doors. The actual physical location does not exist anymore due to other buildings in the area but I believe there is a marker in the sidewalk near-by.80 years ago today, The Cocoanut Grove fire, Boston, MA Box 1521. A 5 alarm fire claiming the lives of 492 people with another 166 injured. A fire resulting in the changes and implementation of multiple fire codes.

Last edited:

November 28, 1942 - The Cocoanut Grove Fire Kills 492 People. Boston, MA.

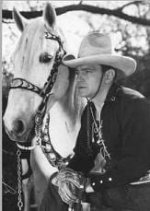

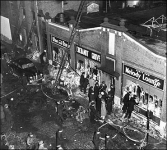

On Saturday, November 28, 1942 Boston's Cocoanut Grove nightclub was the site of one of the deadliest fires in American history. The image had been crafted with care to suggest a festive tropical paradise with just a touch of the illicit ambience of a Prohibition-era speakeasy. It was a curious mix for a nightclub, yet it worked. But the lasting image seared upon the psyche of this city is of bodies "stacked like cordwood" along Shawmut and Piedmont streets awaiting transport to area morgues in the aftermath of the fire. The night spot was owned by Barney Welansky who had connections to both the mayor and organized crime. The Cocoanut Grove Nightclub was located at 17 Piedmont St. It was quaintly reminiscent of Rick's Cafe American in the movie Casablanca--but its highly flammable tropical-style furniture and decorations made it a firetrap. There were more than 1,000 people inside although the legal capacity was 460. The fire is believed to have started at approximately 10:15 pm in the club's Melody Lounge. Patrons were relaxing among the palm fronds under the blue satin ceiling fabric, when a busboy attempted to replace a light bulb in the dimly lit Melody Lounge in the lower level. He struck a match to help him see. Shortly thereafter patrons saw the palm fronds from a nearby artificial tree ignite. The fire rapidly spread along the walls and ceiling. Within five minutes the entire nightclub was ablaze. A few blocks away, firefighters were extinguishing a car fire when they saw smoke at the nightclub and headed that direction. The fire response ultimately included 187 firefighters, 26 engine companies, five ladder companies, three rescue companies and one water tower. Many patrons attempted to exit through the revolving main door which quickly became jammed. Some secondary doors had been welded shut to prevent customers from leaving without paying their tabs. Other doors swung inward and made escape nearly impossible due to the crush of the crowd. All told, 492 people perished. Fire officials later testified that, had the doors swung outward, at least 300 lives could have been spared. Additionally, the building did not have an automatic fire sprinkler system. Among the fatalities were Cowboy movie star Buck Jones and a couple who had been married earlier that same day. Welansky was convicted on multiple counts of involuntary manslaughter.

In the days after the fire there were many stories told of the acts of bravery that had taken place on that dreadful night.

A Gloucester sailor, Stanley Viator, was passing by the club's Shawmut Street door when the blaze broke out. Three times he rushed inside and dragged patrons to safety. He never emerged from his fourth rescue attempt.

Coast Guardsman Clifford Johnson raced into the New Lounge four times to rescue trapped patrons before he was engulfed in flames. Second- and third- degree burns covered more than 60 percent of his body. His courage and devotion were matched by doctors and nurses at Boston City Hospital who patiently and skillfully restored his life and mobility through long months of painstaking treatment.

More than 300 victims, living and dead, would arrive at the doors of Boston City Hospital within an hour of the blaze. Never before had such demands been placed on a US medical institution.

Cocoanut Grove - Disasters of the Century

On Saturday, November 28, 1942 Boston's Cocoanut Grove nightclub was the site of one of the deadliest fires in American history. The image had been crafted with care to suggest a festive tropical paradise with just a touch of the illicit ambience of a Prohibition-era speakeasy. It was a curious mix for a nightclub, yet it worked. But the lasting image seared upon the psyche of this city is of bodies "stacked like cordwood" along Shawmut and Piedmont streets awaiting transport to area morgues in the aftermath of the fire. The night spot was owned by Barney Welansky who had connections to both the mayor and organized crime. The Cocoanut Grove Nightclub was located at 17 Piedmont St. It was quaintly reminiscent of Rick's Cafe American in the movie Casablanca--but its highly flammable tropical-style furniture and decorations made it a firetrap. There were more than 1,000 people inside although the legal capacity was 460. The fire is believed to have started at approximately 10:15 pm in the club's Melody Lounge. Patrons were relaxing among the palm fronds under the blue satin ceiling fabric, when a busboy attempted to replace a light bulb in the dimly lit Melody Lounge in the lower level. He struck a match to help him see. Shortly thereafter patrons saw the palm fronds from a nearby artificial tree ignite. The fire rapidly spread along the walls and ceiling. Within five minutes the entire nightclub was ablaze. A few blocks away, firefighters were extinguishing a car fire when they saw smoke at the nightclub and headed that direction. The fire response ultimately included 187 firefighters, 26 engine companies, five ladder companies, three rescue companies and one water tower. Many patrons attempted to exit through the revolving main door which quickly became jammed. Some secondary doors had been welded shut to prevent customers from leaving without paying their tabs. Other doors swung inward and made escape nearly impossible due to the crush of the crowd. All told, 492 people perished. Fire officials later testified that, had the doors swung outward, at least 300 lives could have been spared. Additionally, the building did not have an automatic fire sprinkler system. Among the fatalities were Cowboy movie star Buck Jones and a couple who had been married earlier that same day. Welansky was convicted on multiple counts of involuntary manslaughter.

In the days after the fire there were many stories told of the acts of bravery that had taken place on that dreadful night.

A Gloucester sailor, Stanley Viator, was passing by the club's Shawmut Street door when the blaze broke out. Three times he rushed inside and dragged patrons to safety. He never emerged from his fourth rescue attempt.

Coast Guardsman Clifford Johnson raced into the New Lounge four times to rescue trapped patrons before he was engulfed in flames. Second- and third- degree burns covered more than 60 percent of his body. His courage and devotion were matched by doctors and nurses at Boston City Hospital who patiently and skillfully restored his life and mobility through long months of painstaking treatment.

More than 300 victims, living and dead, would arrive at the doors of Boston City Hospital within an hour of the blaze. Never before had such demands been placed on a US medical institution.

Cocoanut Grove - Disasters of the Century

BOSTON FIRE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The Story of the Cocoanut Grove Fire

The Cocoanut Grove Fire

November 28, 1942

2220 Hours, Box 1521, 5 Alarms

View from the Melody Lounge up the 4-foot wide staircase, the only public means of egress.

Special Cocoanut Grove Section containing documents & historical information.

The Cocoanut Grove was a restaurant/supper club (nightclubs did not officially exist in Boston), built in 1927 and located at 17 Piedmont Street, near Park Square, in downtown Boston, Massachusetts. Piedmont Street was a narrow cobblestoned street (now paved) located near the Park Square theater district, running from Arlington Street to Broadway.

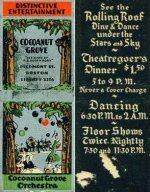

The Cocoanut Grove had been very popular in the late 1920’s, due to Prohibition, but had fallen on hard times during the 1930’s. It became very popular once again during the early years of World War II. In 1942 the owner for the three years previous years had been a lawyer named Barnet (Barney) Welansky. The Grove was the place to be in 1942. The building was a single-story structure, with a basement beneath. The basement contained a bar, called the Melody Lounge, along with the kitchen, freezers, and storage areas. The first floor contained a large dining room area and ballroom with a bandstand, along with several bar areas separate from the ballroom. The dining room also had a retractable roof for use during warm weather to allow a view of the moon and stars. The main entrance to the Cocoanut Grove was via a revolving door on the Piedmont Street side of the building.

On Saturday, November 28, 1942, the powerful Boston College (BC) football team had played Holy Cross College (HC) at Fenway Park. In a great upset of that period, HC beat BC by a score of 55-12. College bowl game scouts had attended the game in order to offer BC a bid to the 1943 Sugar Bowl game, a bowl BC had previously won on January 1, 1941. As a result of the rout a BC bowl game celebration party scheduled for the Grove that evening was canceled. BC later accepted a bid to play in the Orange Bowl on January 1, 1943, subsequently losing to the University of Alabama.

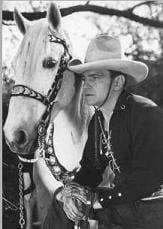

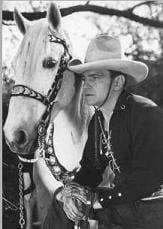

A famous Hollywood cowboy movie star, Buck Jones (real name Charles Gebhart)(photo right), was traveling the country on a War Bond campaign, had attended the BC-HC football game with Boston Mayor Maurice Tobin. Despite his reluctance due to illness, Buck was persuaded by movie agents to have dinner that evening at the Grove.

At about 10:15PM that evening, a busboy had been ordered by a bartender to fix a light bulb located at the top of an artificial palm tree in the corner of the basement Melody Lounge. It is believed that the bulb had been unscrewed by a patron desiring more intimacy with his date. Due to the lack of light in the area of the palm tree, the busboy lit a match in order to locate the socket for the light bulb.

A moment later, several patrons thought they saw a flicker of a flame in the palm tree of the ceiling decorations. As they watched, they saw the decorations change color and appeared to be burning, but without a noticeable flame. After several moments, the palm tree burst into flames and the bartenders tried to extinguish the fire with water and seltzer bottles. Some patrons started for the only public exit from the Melody Lounge, a four-foot wide set of stairs leading to the Foyer on the first floor. As other furnishings ignited, a fireball of flame and toxic gas raced across the room toward the stairs. A wild panic ensued and attempts to open the emergency exit door at the top of the stairs were not successful. The fireball traveled up the stairs and burst into the Foyer area, where coatrooms, restrooms and the main entrance were located. Amid cries of “Fire, Fire”, customers quickly moved to toward the exit. After a small number of people exited, the revolving door became jammed due to the crush of panicked patrons. Observers outside could only watch in horror as relatives and friends were crushed by the weight of the crowd surging against the jammed door.

The fireball then exploded into the Dining Room area, where a majority of the patrons were crowded together into small chairs and tables, awaiting the start of the 10PM show, already fifteen minutes late. It was later estimated that more than 1000 persons were inside the Grove at the time of the fire. As with the Melody Lounge, panic ensued and customers attempted to find an exit. Unfortunately, many exits were either locked shut or were not easily indentified or accessed by the crowd. The fire now had complete control of the premises, with a tremendous rise in temperature and high levels of toxic gas.

In a strange coincidence, at 10:15PM, the Boston Fire Department received and transmitted Box 1514, located at Stuart and Carver Streets, located about three blocks from the Cocoanut Grove. Upon arrival and investigation, firefighters found an automobile fire on Stuart Street. After quickly extinguishing the fire, a firefighter noticed what appeared to be smoke coming from the Cocoanut Grove. As they began to investigate, bystanders ran toward them to report the fire. Upon arrival at the Grove, firefighters found a heavy smoke condition emanating from the entire building, with both patrons and employees escaping from the building. At 10:20PM, the Boston Fire Alarm Office (FAO) received Box 1521, Church and Winchester Streets, apparently pulled by a civilian bystander. The fire chief at the scene ordered his aide to skip the Second Alarm and request a Third Alarm, via fire alarm telegraph, from Box 1521, which was transmitted at 10:23PM, followed by a Fourth Alarm at 10:24PM. A Fifth Alarm was transmitted at 11:02PM.

The Boston Fire Department Running Card for Box 1521, in effect at the time of the Cocoanut Grove Fire, is below. The response to each of five alarms is read horizontally from left to right.

The Cocoanut Grove had been very popular in the late 1920’s, due to Prohibition, but had fallen on hard times during the 1930’s. It became very popular once again during the early years of World War II. In 1942 the owner for the three years previous years had been a lawyer named Barnet (Barney) Welansky. The Grove was the place to be in 1942. The building was a single-story structure, with a basement beneath. The basement contained a bar, called the Melody Lounge, along with the kitchen, freezers, and storage areas. The first floor contained a large dining room area and ballroom with a bandstand, along with several bar areas separate from the ballroom. The dining room also had a retractable roof for use during warm weather to allow a view of the moon and stars. The main entrance to the Cocoanut Grove was via a revolving door on the Piedmont Street side of the building.

On Saturday, November 28, 1942, the powerful Boston College (BC) football team had played Holy Cross College (HC) at Fenway Park. In a great upset of that period, HC beat BC by a score of 55-12. College bowl game scouts had attended the game in order to offer BC a bid to the 1943 Sugar Bowl game, a bowl BC had previously won on January 1, 1941. As a result of the rout a BC bowl game celebration party scheduled for the Grove that evening was canceled. BC later accepted a bid to play in the Orange Bowl on January 1, 1943, subsequently losing to the University of Alabama.

A famous Hollywood cowboy movie star, Buck Jones (real name Charles Gebhart)(photo right), was traveling the country on a War Bond campaign, had attended the BC-HC football game with Boston Mayor Maurice Tobin. Despite his reluctance due to illness, Buck was persuaded by movie agents to have dinner that evening at the Grove.

At about 10:15PM that evening, a busboy had been ordered by a bartender to fix a light bulb located at the top of an artificial palm tree in the corner of the basement Melody Lounge. It is believed that the bulb had been unscrewed by a patron desiring more intimacy with his date. Due to the lack of light in the area of the palm tree, the busboy lit a match in order to locate the socket for the light bulb.

A moment later, several patrons thought they saw a flicker of a flame in the palm tree of the ceiling decorations. As they watched, they saw the decorations change color and appeared to be burning, but without a noticeable flame. After several moments, the palm tree burst into flames and the bartenders tried to extinguish the fire with water and seltzer bottles. Some patrons started for the only public exit from the Melody Lounge, a four-foot wide set of stairs leading to the Foyer on the first floor. As other furnishings ignited, a fireball of flame and toxic gas raced across the room toward the stairs. A wild panic ensued and attempts to open the emergency exit door at the top of the stairs were not successful. The fireball traveled up the stairs and burst into the Foyer area, where coatrooms, restrooms and the main entrance were located. Amid cries of “Fire, Fire”, customers quickly moved to toward the exit. After a small number of people exited, the revolving door became jammed due to the crush of panicked patrons. Observers outside could only watch in horror as relatives and friends were crushed by the weight of the crowd surging against the jammed door.

The fireball then exploded into the Dining Room area, where a majority of the patrons were crowded together into small chairs and tables, awaiting the start of the 10PM show, already fifteen minutes late. It was later estimated that more than 1000 persons were inside the Grove at the time of the fire. As with the Melody Lounge, panic ensued and customers attempted to find an exit. Unfortunately, many exits were either locked shut or were not easily indentified or accessed by the crowd. The fire now had complete control of the premises, with a tremendous rise in temperature and high levels of toxic gas.

In a strange coincidence, at 10:15PM, the Boston Fire Department received and transmitted Box 1514, located at Stuart and Carver Streets, located about three blocks from the Cocoanut Grove. Upon arrival and investigation, firefighters found an automobile fire on Stuart Street. After quickly extinguishing the fire, a firefighter noticed what appeared to be smoke coming from the Cocoanut Grove. As they began to investigate, bystanders ran toward them to report the fire. Upon arrival at the Grove, firefighters found a heavy smoke condition emanating from the entire building, with both patrons and employees escaping from the building. At 10:20PM, the Boston Fire Alarm Office (FAO) received Box 1521, Church and Winchester Streets, apparently pulled by a civilian bystander. The fire chief at the scene ordered his aide to skip the Second Alarm and request a Third Alarm, via fire alarm telegraph, from Box 1521, which was transmitted at 10:23PM, followed by a Fourth Alarm at 10:24PM. A Fifth Alarm was transmitted at 11:02PM.

The Boston Fire Department Running Card for Box 1521, in effect at the time of the Cocoanut Grove Fire, is below. The response to each of five alarms is read horizontally from left to right.

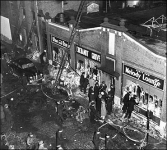

The small, congested streets in the area of the Grove quickly became clogged with fire apparatus and other emergency vehicles. The fire was extinguished in a matter of minutes, but the damage had already been done. Rescue operations began immediately, but the full horror of what awaited the firefighters inside the building was not fully realized for a period of time. Many patrons who were able to exit under their own power collapsed in the street and stacks of bodies, both living and dead, were buried shoulder-high at many of the exits. Getting inside to help proved nearly as difficult as getting out.

Many patrons were aided in escaping by following employees through the dark back corridors (the lights had gone out shortly after the fire started), while others hid in the giant refrigerators and meat lockers. Others were able to open several concealed exit doors from the Dining Room. However, due to the rapid spread of the fire, the intense heat and toxic smoke, many patrons inside the Grove never had a chance. An exit door in the newly-opened, but officially unlicensed ‘New Lounge’ allowed for the escape of some patrons. However, because the door was installed as an inward-opening door, the rush and weight of those fleeing the fire caused the door to shut, cutting off an important escape route. Other employees escaped through windows in various parts of the Grove, principally because they knew their way around in the back areas.

When the magnitude of the disaster was realized, an urgent call for help was issued. Navy, Army, Coast Guard and National Guard personnel were called in to assist in the evacuation and removal of the injured. Newspaper delivery trucks, taxis, and any other means were used to transport the injured. In an interesting twist of fate, area hospitals had practiced a disaster drill the week before the fire. Despite the drill, the majority of the injured were taken to Boston City Hospital (BCH). Many others were taken to Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Orther area hospitals received some victims, and could have taken more under a more coordinated victim evacuation plan. BCH received 300 victims in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds. This volume exceeds the treatment rate encountered in London during the Blitz. MGH received 114 victims in two hours. Off-duty staffs were called in at both BCH and MGH, while volunteers provided additional assistance.

A temporary morgue was established in film distribution garage nearby the Grove. A number of presumed dead victims were sent directly to either the Northern Mortuary or Southern Mortuary. Several presumed dead victims, dropped off at the morgue, were actually alive. They were moved to the hospital and survived. At the morgues, staff and volunteers worked to identify the deceased. Identifying female victims was difficult because personal identification was usually kept in purses or handbags, which became separated from the owners in the panic and confusion of the fire.

Cocoanut Grove owner Barney Welansky had suffered a heart attack twelve days prior to the fire. While injured patrons of his establishment were being treated in the lobby of MGH, Welansky was upstairs resting in a bed. Buck Jones, who did not survive after lingering for two days, was among the victims sent to MGH. Doctors and nurses worked to save the injured, while other personnel worked to identify the victims.

Treatment of burns and internal injuries on such as massive scale caused medical personnel to adopt newly developed methods of care. Some methods had been well tested, while others had not. The first recorded general (non-test patients) use of penicillin to fight infection on burn victims occurred at MGH on December 2, 1942.

A ‘soft’ technique of treating burns was tried at MGH, under the leadership of Dr. Oliver Cope, by treating the affected skin areas with a solution of boric petroleum. Purple dyes were used at BCH to coat the skin and to fight infection. Skin grafts were used to help in the healing process. In all, advances in burn treatment were made in four categories: fluid retention; prevention infection; treating respiratory trauma; skin surface and surgical management. It was discovered that many victims, both at the scene and at the hospital, succumbed to pulmonary edema. The edema was caused by breathing-in toxic smoke and gases containing ‘pyrolysis’, which was caused by the burning of the furniture and furnishings inside the Grove.

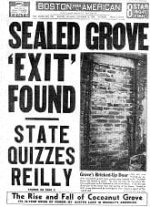

In the aftermath of the fire, investigations were conducted by several agencies. Fire Commissioner William Reilly’s probe started on Sunday, November 29. Testimony was heard from many witnesses as to the facts surrounding the disaster. Most believed that the busboy was responsible, but others believed the cause was electrical. A Grand Jury would later indict ten persons, but the only person convicted of a crime was the owner, Barney Welansky, on one count of manslaughter. He was sentence to 12-15 years in Charlestown State Prison. Due to an advanced cancer condition, he was pardoned by Governor Maurice Tobin after serving 3.5 years. He died in 1947, at age 50, several months after his release from prison.

Building codes were amended in the city and elsewhere. Revolving doors were outlawed (later reinstated when a revolving door is placed between two outward-opening exit doors). Exit doors were to be clearly marked, be unlocked from within, and free from blockage by screen, drapes, furniture or business supplies. Use of non-combustible decorations and building materials was ordered, as was the placement of emergency lighting and sprinklers. Popular lore has it that the name ‘Cocoanut Grove’ was outlawed in the city of Boston. That did not occur, however no business since the fire has proposed or been licensed to use the name ‘Cocoanut Grove’.

The final death count established by Commissioner Reilly was 490 dead and 166 injured. The number of injured was a count of those treated at a hospital and later released. Many other patrons were injured but did not seek hospitalization. As the years went by, the recognized number of fatalities became 492. This count of dead in a single fire event is exceeded only by Chicago’s Iroquois Theatre Fire of December 30, 1903 which killed 603 persons, mostly children. Also, the attacks September 11, 2001 on the World Trade Center in New York killed approximately 2,750 persons, but the event was a combination fire and collapse event.

List of the Cocoanut Grove Fatalities List of the Cocoanut Grove InjuredMany patrons were aided in escaping by following employees through the dark back corridors (the lights had gone out shortly after the fire started), while others hid in the giant refrigerators and meat lockers. Others were able to open several concealed exit doors from the Dining Room. However, due to the rapid spread of the fire, the intense heat and toxic smoke, many patrons inside the Grove never had a chance. An exit door in the newly-opened, but officially unlicensed ‘New Lounge’ allowed for the escape of some patrons. However, because the door was installed as an inward-opening door, the rush and weight of those fleeing the fire caused the door to shut, cutting off an important escape route. Other employees escaped through windows in various parts of the Grove, principally because they knew their way around in the back areas.

When the magnitude of the disaster was realized, an urgent call for help was issued. Navy, Army, Coast Guard and National Guard personnel were called in to assist in the evacuation and removal of the injured. Newspaper delivery trucks, taxis, and any other means were used to transport the injured. In an interesting twist of fate, area hospitals had practiced a disaster drill the week before the fire. Despite the drill, the majority of the injured were taken to Boston City Hospital (BCH). Many others were taken to Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Orther area hospitals received some victims, and could have taken more under a more coordinated victim evacuation plan. BCH received 300 victims in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds. This volume exceeds the treatment rate encountered in London during the Blitz. MGH received 114 victims in two hours. Off-duty staffs were called in at both BCH and MGH, while volunteers provided additional assistance.

A temporary morgue was established in film distribution garage nearby the Grove. A number of presumed dead victims were sent directly to either the Northern Mortuary or Southern Mortuary. Several presumed dead victims, dropped off at the morgue, were actually alive. They were moved to the hospital and survived. At the morgues, staff and volunteers worked to identify the deceased. Identifying female victims was difficult because personal identification was usually kept in purses or handbags, which became separated from the owners in the panic and confusion of the fire.

Cocoanut Grove owner Barney Welansky had suffered a heart attack twelve days prior to the fire. While injured patrons of his establishment were being treated in the lobby of MGH, Welansky was upstairs resting in a bed. Buck Jones, who did not survive after lingering for two days, was among the victims sent to MGH. Doctors and nurses worked to save the injured, while other personnel worked to identify the victims.

Treatment of burns and internal injuries on such as massive scale caused medical personnel to adopt newly developed methods of care. Some methods had been well tested, while others had not. The first recorded general (non-test patients) use of penicillin to fight infection on burn victims occurred at MGH on December 2, 1942.

A ‘soft’ technique of treating burns was tried at MGH, under the leadership of Dr. Oliver Cope, by treating the affected skin areas with a solution of boric petroleum. Purple dyes were used at BCH to coat the skin and to fight infection. Skin grafts were used to help in the healing process. In all, advances in burn treatment were made in four categories: fluid retention; prevention infection; treating respiratory trauma; skin surface and surgical management. It was discovered that many victims, both at the scene and at the hospital, succumbed to pulmonary edema. The edema was caused by breathing-in toxic smoke and gases containing ‘pyrolysis’, which was caused by the burning of the furniture and furnishings inside the Grove.

In the aftermath of the fire, investigations were conducted by several agencies. Fire Commissioner William Reilly’s probe started on Sunday, November 29. Testimony was heard from many witnesses as to the facts surrounding the disaster. Most believed that the busboy was responsible, but others believed the cause was electrical. A Grand Jury would later indict ten persons, but the only person convicted of a crime was the owner, Barney Welansky, on one count of manslaughter. He was sentence to 12-15 years in Charlestown State Prison. Due to an advanced cancer condition, he was pardoned by Governor Maurice Tobin after serving 3.5 years. He died in 1947, at age 50, several months after his release from prison.

Building codes were amended in the city and elsewhere. Revolving doors were outlawed (later reinstated when a revolving door is placed between two outward-opening exit doors). Exit doors were to be clearly marked, be unlocked from within, and free from blockage by screen, drapes, furniture or business supplies. Use of non-combustible decorations and building materials was ordered, as was the placement of emergency lighting and sprinklers. Popular lore has it that the name ‘Cocoanut Grove’ was outlawed in the city of Boston. That did not occur, however no business since the fire has proposed or been licensed to use the name ‘Cocoanut Grove’.

The final death count established by Commissioner Reilly was 490 dead and 166 injured. The number of injured was a count of those treated at a hospital and later released. Many other patrons were injured but did not seek hospitalization. As the years went by, the recognized number of fatalities became 492. This count of dead in a single fire event is exceeded only by Chicago’s Iroquois Theatre Fire of December 30, 1903 which killed 603 persons, mostly children. Also, the attacks September 11, 2001 on the World Trade Center in New York killed approximately 2,750 persons, but the event was a combination fire and collapse event.

The lessons of the Cocoanut Grove are with us every day. Exits blocked or locked, smoking and use of matches, overcrowding, flammable materials within buildings and a lack of sprinklers and smoke detectors. Hardly a person in Boston or New England during the 1940’s could be found who did not have a friend or relative who wasn’t at the Grove that night, or had planned to go, or had left before the fire started, or wasn’t affected by this tragedy. The question then and now is: “Can this happen again”? The answer is yes, it can and will happen again. The ‘Station Nightclub Fire’ in West Warwick, RI, on February 20, 2003 claimed the lives of 100 persons and injured approximately 200 others. Many of the same causes and lessons experienced at the Cocoanut Grove caused this tragedy.

A survivor’s own story (from the Brockton Enterprise, via YouTube)

The site of the Cocoanut Grove has been dramatically changed over the years since 1942. With the erection of hise-rise hotel/theatre complex, the streets around Piedmont Street were altered. Broadway now only runs two blocks from Melrose Street to Piedmont Street. Shawmut Street now makes a ninety-degree turn and intersects with Piedmont Street, near the location of the Cocoanut Grove’s revolving door. The hotel now covers most of the land area where the Cocoanut Grove stood. A bronze memorial plaque was placed in the brick sidewalk in 1993 by the Bay Village Neighborhood Association and a marker was placed on the wall of the hotel by the Bostonian Society.

bostonfirehistory.org

bostonfirehistory.org

The Story of the Cocoanut Grove Fire - Boston Fire Historical Society

The Cocoanut Grove Fire November 28, 1942 2220 Hours, Box 1521, 5 Alarms Special Cocoanut Grove Section containing documents & historical information. The Cocoanut Grove was a restaurant/supper club (nightclubs […]

bostonfirehistory.org

bostonfirehistory.org