Black Sunday 2005

Deaths of Two Firefighters Raise Issue of Safety Ropes

By Michelle O'Donnell

Jan. 30, 2005

Besides hoses bearing water, few tools have proved as durable and as useful to New York City firefighters as rope. In longstanding rescue practices and on-the-spot improvisations, firefighters have relied on rope since the days when horses pulled engines and volunteers fought fires, right through last Sunday when two firefighters used a rope to escape a burning building in the Bronx.

In that fire, however, four other firefighters did not have ropes and jumped from the fourth floor. Two died. In the aftermath, Fire Commissioner Nicholas Scoppetta said that that he would consider making ropes standard gear for every firefighter. Doing so would give them a tool with a rich history, but would add more weight to what is already a hefty load.

The uses of ropes by firefighters have expanded for more than a century, just as the city has. With buildings rising to greater heights, firefighters used ropes to lower people to safety. They still do. Firefighters also tie a rope when they enter a vast smoke-filled space and hold the line so they can find their way out. And ropes are used to hoist equipment at emergencies.

But perhaps the most crucial use of rope is as a self-contained fire escape for firefighters themselves. Fire Department ladders outside buildings cannot always be mounted in time to reach trapped firefighters. But a rope, carried in a firefighter's coat pocket, can be quickly unfurled.

The lifesaving utility of a rope was apparent last Sunday. Two firefighters from Rescue 3 who were trapped by fire in a room on the fourth floor of 236 East 178th Street, Jeffrey G. Cool and Joseph P. DiBernardo, quickly fastened a length of rope to child safety bars attached to a window, each taking a turn to lower himself part of the way to the ground.

That sort of desperate utility led the department in 1990 to order that all 11,000 firefighters be equipped with a personal safety rope, but the department abandoned that regulation in 2000.

The nylon ropes, which were three-eighths of an inch thick and 40 feet long, came coiled in a pouch that could be stored in the jacket pockets of the gear that firefighters wore and were attached to harnesses around their waists.

Some firefighters liked carrying a safety rope for emergencies. "You knew that you had a way out," said one former firefighter.

But some firefighters complained about the rope's bulk, especially after 1994, when the department issued heavier protective bunker gear with jackets that had shallower pockets than the old coats.

Other equipment changes during the 1990's required firefighters to carry more, including tools to break down doors, infrared cameras to search for fire through walls, fire protective hoods and harnesses that looped around a firefighter's waist and bunker pants. A firefighting coat, pants, boots and a helmet weigh a total of 29 1/2 pounds. Adding an oxygen tank brings the weight of basic equipment to 56 1/2 pounds. But some firefighters bearing additional tools can carry as much as 94 1/2 pounds

In 2000, the department recalled all the ropes close to the expiration date of their safety certification and did not issue new ones. At the same time, the department reduced the number of personal safety harnesses it issued; these are used to attach to the two-person rescue rope that each company carries. The two unions that represents firefighters and officers filed a contract grievance against the city over the reduction of the harnesses, but an independent arbitrator ruled in favor of the city in August 2001, said Michael Axelrod, a lawyer for the Uniformed Firefighters Association.

Although the unions complained that the department was continuing a pattern of not investing in vital equipment, Thomas Von Essen, the fire commissioner when the ropes were withdrawn, said the reaction of some firefighters to the ropes led to the decision to discontinue their use.

"There were a lot of complaints in the field about the extra weight," Mr. Von Essen said. "It was one of the areas we felt the least critical at the time, to take these out.

"There was no reason for a lot of people to use them. We wish every firefighter could be carrying his own infrared camera and roof rope, but there's a limit to how much each man can carry."

Daniel Nigro, who retired as chief of the department in 2002, said he had heard complaints that the use of the personal harnesses was wearing out firefighting pants for which the department had paid $10 million. But he said he did not know if cost concerns had played a role in the decision to withdraw the ropes. "That's something they have to look at now when they revisit why the department went away from that and should they go back," Mr. Nigro said.

The city has opened several inquiries into the problems at the Bronx fire, including investigating why a loss of water pressure left firefighters on the third floor without water, requiring firefighters with a hose on the fourth floor to go down and help douse the fire.

Investigators are also trying to determine who built an illegal partition in a fourth-floor apartment that prevented six firefighters from reaching a fire escape. While there is little doubt that a series of failures left the firefighters trapped, it is clear that ropes proved critical as the drama on the fourth floor unfolded.

A breathing mask was lowered from the roof to the trapped men by what is believed to be a utility rope, said Chief Joseph Callan, the Bronx borough commander. Moments later the fire from the third floor burst through to the fourth, and that is when Firefighters Cool and DiBernardo lashed onto the window bars a rope that Firefighter Cool happened to be carrying.

For reasons not yet known, both men fell during their descent. Firefighter Cool, who went first, fell halfway down, and Firefighter DiBernardo fell when he was just 10 feet below the window, according to Firefighter DiBernardo's father, Joseph DiBernardo Sr., a retired deputy chief. Both men were critically injured.

Fire officials said they were still investigating the falls and could not say if the rope had snapped, how long it was or if the men had instinctively let go because the ropes burned their hands as they slid down.

Trapped in another room were the four firefighters who did not have rope and who jumped. Lt. Curtis W. Meyran and Firefighter John G. Bellew died as a result of their fall.

The two other firefighters, Brendan K. Cawley and Eugene Stolowski, suffered critical injuries and are still in a hospital.

From the roof, a firefighter from Squad 41 -- using a two-person rescue rope issued by the department, called a lifesaving rope -- was lowering himself to the fourth floor when the last of the men fell.

Of the six firefighters, all but Firefighter Cawley wore a safety harness, a Fire Department official said.

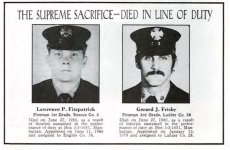

In 1980, two firefighters, Lawrence Fitzpatrick and Gerard Frisby, fell to their deaths in Harlem when the rope they were holding snapped. A five-month inquiry by the city's Department of Investigation faulted the department for "unprofessionally" handling its investigation of the accident and ignoring reports that the rope it had issued was insufficient.

Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, speaking on Friday on his weekly radio program on WABC-AM, said it was impossible to say for sure whether ropes would have saved the lives of the two firefighters in the Bronx.

"So we'll see whether they want to change it," the mayor said, referring to top Fire Department officials.

"But you know, sometimes things help, and sometimes they don't, and you have to look at it on balance, and you pray that the right decision was made for the right time. Unfortunately, there's no one answer for everything."

Deaths of two firefighters in leap from blazing Bronx building on Jan 23 put focus on safety ropes; two firefighters used same rope to escape building; four others did not have ropes and jumped from building's fourth floor; both firefighters who used rope fell during their descents for reasons...

www.nytimes.com

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/XX4F5K73ARBEBE3EL2V77KWNR4.jpg)