Last edited:

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FIRE DEPARTMENTS IN NY STATE

- Thread starter mack

- Start date

NEW ROCHELLE

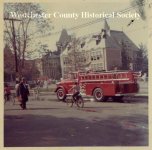

The New Rochelle High School Fire of 1968

The first fire alarm was sounded at 7:22 am, twenty-three minutes before the beginning of first period. All students and personnel exited the building safely although the workman who discovered the library fire was hospitalized in critical condition for smoke inhalation. Within minutes the flames quickly spread upwards through an elevator shaft. The fire traveled into a cockloft, or loft, running along the wooden roof and then expanding across the structure.

At 9:11 am, a three alarm fire was declared. By 10 am, the auditorium roof had collapsed, destroying a beautiful theatre and its collection of costumes and flats. Both thick smoke and flames were visible from the campus as the fire continued to spread.

Although this was a sunny, spring day, wind blowing twenty miles per hour from the northwest fanned the flames. This wind caused the fire to move quickly across the roof and made combatting the blaze even more difficult.

Workers removed enclosures around the construction site of the new library, in front of the building, so fire apparatus would have access to the school's right wing.

At noon, the school editor for The Standard Star newspaper reported that "it appeared the building will be completely destroyed." When it became apparent that the fire was out of control, staff entered the building to retrieve permanent records from the administration wing, as shown in the photograph on the Home page.

Students were seen on school grounds, stunned as the fire consumed their school, wondering what would become of the remaining school year, crying.

The fire was declared extinguished by 2 pm, but firemen continued to wet the smoldering cinders throughout that afternoon and night.

The fire burned through the roof between the three Gothic towers, gutting much of the structure below. The original façade of red brick and limestone survived. The main tower stood intact in the center of the ruins, with its clock stopped at 9:25 am. Spared were the 1959-60 wings and the foundation under construction for the new library.

To battle the blaze, the New Rochelle Fire Department was assisted by fire fighters from Eastchester, Mount Vernon, Larchmont, Mamaroneck, Pelham Manor and North Pelham for a total of 150 men. About sixteen pieces of fire equipment were employed and water was pumped from the Twin Lakes to battle the blaze. Five firemen were injured by the day's end.

The fact that there had been other earlier fires in the school, that at least three torches had been found, and fires appeared in multiple locations left no doubt as to its origin. The Police Commission characterized the cause of the fire by stating, "arson- no question." The Public Safety Commissioner declared the fire to be a case of arson, so a fire watch was declared for all New Rochelle schools on a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week basis.

An arson investigation was begun immediately. Forty-five teachers were individually interviewed on the afternoon of the fire by New Rochelle detectives to obtain any helpful information.

The New Rochelle High School Fire of 1968

The Fire

May 17, 1968The first fire alarm was sounded at 7:22 am, twenty-three minutes before the beginning of first period. All students and personnel exited the building safely although the workman who discovered the library fire was hospitalized in critical condition for smoke inhalation. Within minutes the flames quickly spread upwards through an elevator shaft. The fire traveled into a cockloft, or loft, running along the wooden roof and then expanding across the structure.

At 9:11 am, a three alarm fire was declared. By 10 am, the auditorium roof had collapsed, destroying a beautiful theatre and its collection of costumes and flats. Both thick smoke and flames were visible from the campus as the fire continued to spread.

Although this was a sunny, spring day, wind blowing twenty miles per hour from the northwest fanned the flames. This wind caused the fire to move quickly across the roof and made combatting the blaze even more difficult.

Workers removed enclosures around the construction site of the new library, in front of the building, so fire apparatus would have access to the school's right wing.

At noon, the school editor for The Standard Star newspaper reported that "it appeared the building will be completely destroyed." When it became apparent that the fire was out of control, staff entered the building to retrieve permanent records from the administration wing, as shown in the photograph on the Home page.

Students were seen on school grounds, stunned as the fire consumed their school, wondering what would become of the remaining school year, crying.

The fire was declared extinguished by 2 pm, but firemen continued to wet the smoldering cinders throughout that afternoon and night.

The fire burned through the roof between the three Gothic towers, gutting much of the structure below. The original façade of red brick and limestone survived. The main tower stood intact in the center of the ruins, with its clock stopped at 9:25 am. Spared were the 1959-60 wings and the foundation under construction for the new library.

To battle the blaze, the New Rochelle Fire Department was assisted by fire fighters from Eastchester, Mount Vernon, Larchmont, Mamaroneck, Pelham Manor and North Pelham for a total of 150 men. About sixteen pieces of fire equipment were employed and water was pumped from the Twin Lakes to battle the blaze. Five firemen were injured by the day's end.

The fact that there had been other earlier fires in the school, that at least three torches had been found, and fires appeared in multiple locations left no doubt as to its origin. The Police Commission characterized the cause of the fire by stating, "arson- no question." The Public Safety Commissioner declared the fire to be a case of arson, so a fire watch was declared for all New Rochelle schools on a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week basis.

An arson investigation was begun immediately. Forty-five teachers were individually interviewed on the afternoon of the fire by New Rochelle detectives to obtain any helpful information.

The Fire of May 17, 1968

A description with photographs of the arson fire that destroyed New Rochelle High School in 1968.

nrhs1968.weebly.com

NEW ROCHELLE

NRFD RESPONDING

NRFD OPERATING

www.youtube.com

www.youtube.com

www.youtube.com

www.youtube.com

www.youtube.com

www.youtube.com

www.youtube.com

www.youtube.com

NRFD RESPONDING

NRFD OPERATING

2-14-11: New Rochelle, N.Y. Five-Alarm Church Fire

A dramatic overnight fire ravaged the historic 99-year-old Union Baptist Church. (Video by Joe Scurto/FireLineVideo.com)

New Rochelle : Three Alarm Fire.90 Union st .

Enjoy the videos and music you love, upload original content, and share it all with friends, family, and the world on YouTube.

New Rochelle firefighters operating at this fully involved detached garage fire 6-10-20

Enjoy the videos and music you love, upload original content, and share it all with friends, family, and the world on YouTube.

Fire at a New Rochelle High-rise building

December 4 2022 New Rochelle, New York - Electrical Fire at High-Rise in Downtown New Rochelle Sparked by Transformer Explosion in Basement; Heavy Smoke, No ...

NEW ROCHELLE

153 dedicated Firefighters that are professionally trained to provide the utmost in public-safety.

The New Rochelle Fire Department is known as the premiere fire department in the area because of its wide range of services and its professionally trained staff. And, with five fire houses strategically stationed throughout the City, when a fire breaks out, or if there's a medical emergency or disaster, help is only a short distance away.

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

153 dedicated Firefighters that are professionally trained to provide the utmost in public-safety.

The New Rochelle Fire Department is known as the premiere fire department in the area because of its wide range of services and its professionally trained staff. And, with five fire houses strategically stationed throughout the City, when a fire breaks out, or if there's a medical emergency or disaster, help is only a short distance away.

New Rochelle Firefighters | New Rochelle NY

New Rochelle Firefighters, New Rochelle. 6,557 likes · 69 talking about this · 182 were here. 153 dedicated Firefighters that are professionally trained to provide the utmost in public-safety.

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

Attachments

Last edited:

NEW ROCHELLE

FIRES

A potential recruit’s exam result will place in an eligibility list, which is then given to the NRFD to be used to fill vacancies.

These exams are given approximately every four (4) years. The last one occurred in 2019.

FIRES

How do I become a New Rochelle Fire Fighter?

The New Rochelle Fire Department (NRFD) employs new recruits in accordance to hiring procedures established under both Federal and New York State Civil Service Law. To be eligible to be hired by the NRFD a potential employee must pass the New York State Fire Fighter Civil Service Exam as given by the New Rochelle Civil Service Commission.A potential recruit’s exam result will place in an eligibility list, which is then given to the NRFD to be used to fill vacancies.

These exams are given approximately every four (4) years. The last one occurred in 2019.

Last edited:

NEW ROCHELLE

MEMORIAL

NRFD LINE OF DUTY DEATHS

10/3/1937 FF WALTER PETERS

12/5/1940 FF OLIVER G. O'DELL

11/10/1962 CHIEF THOMAS CARRIGAN

1/19/1963 CAPT JAMES BURGESS

7/16/1965 FF EARL GEERTGENS

10/8/1983 FF ALAN JONES

7/10/2019 DEP CHIEF FRANK G. STROLLO

5/3/2020 CAPT ANDREW DIMAGGIO

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

MEMORIAL

NRFD LINE OF DUTY DEATHS

10/3/1937 FF WALTER PETERS

12/5/1940 FF OLIVER G. O'DELL

11/10/1962 CHIEF THOMAS CARRIGAN

1/19/1963 CAPT JAMES BURGESS

7/16/1965 FF EARL GEERTGENS

10/8/1983 FF ALAN JONES

7/10/2019 DEP CHIEF FRANK G. STROLLO

5/3/2020 CAPT ANDREW DIMAGGIO

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

Last edited:

SCHENECTADY

The Schenectady Fire Department was formed in 1900, incorporating several disparate fire districts. Today the city is covered by four fire stations: Station 1 in Downtown, Station 2 in Woodlawn, Station 3 in Bellevue, and Station 4 in the Northside.

121 proud men and women are members of the Schenectady Fire Department. These Professional Firefighters are on duty 24/7 to serve the community.

The Schenectady Fire Department serves and safeguards the community from the impacts of fires, medical emergencies, environmental emergencies, and natural disasters through leadership, planning, education, and prevention.

City of Schenectady Fire Department | Schenectady, NY

Fire Chief

Don Mareno

FIRE STATIONS

City of Schenectady Fire Stations

In the past, the City of Schenectady was served by 12 stations in 7 districts, some with a single engine and some with several pieces of fire apparatus and chiefs’ vehicles. Today, through consolidation, that number has been reduced to 4 stations with 4 Engines, 2 Trucks, 2 Rescue vehicles, 2 Hazmat vehicles serving as front-line apparatuses, and 1 Deputy Chief’s car. There are also several Chiefs’ Cars, reserve pieces, and utility vehicles.

Scrapbook 1981: Schenectady dedicates new main fire station - 40 years ago this month - The Daily Gazette

SCHENECTADY - The new Schenectady Fire Department main station was unveiled 40 years ago this month, with dedication ceremonies Oct. 8, 1981. The $2 million facility included advanced telephone technology and radio and telegraph communication systems; living and training facilities for on-duty f

City of Schenectady Fire Stations | Schenectady, NY

Attachments

Last edited:

SCHENECTADY

APPARATUS

Station 1 / Headquarters

Built 1981

Engine 1 - 2021 Rosenbauer Commander

Truck 1 - 2021 Rosenbauer Commander (?/?/100' Cobra mid-mount platform)

Rescue 1 - 2021 Ford F-350 4x4 walk-around

Haz-Mat. Unit 1 - 2001 HME Penetrator walk-around (SN#01F00180) (Ex-East Glenville)

Haz-Mat. Unit 2 - 2010 Ford F-350 / Arrowhead walk-in (Ex-Hazmat 1)

Truck 3 (Reserve) - 2019 Rosenbauer Commander (1500/400/78' rear-mount)

Engine 10 (Reserve) - 2018 Rosenbauer Commander (1500/750) (SN#13978)

Car 19 (Chief) - 200? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

(https://dailygazette.com/2015/08/25/0826_RescueRig/)

Car 20 (Assistant Chief) - 200? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

Car 21 (Assistant Chief) - 200? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

Car 22 (Deputy Chief) - 201? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

Car 25 (Maintenance Unit) - 200? Ford F-350 4x4

2005 Ford Excursion 4x4 (Ex-Hazmat 2)

Station 2

Built 1996

Engine 2 - 2021 Rosenbauer Commander

Truck 2 - 2017 Rosenbauer Commander (2000/300/100' mid-mount platform)

Rescue 2 - 200? Ford Expedition 4x4

Station 3

Built 1938

Engine 3

Truck 3 - 2020/21? Rosenbauer Commander (1500/750/75' rear-mount)

Station 4

Built 1904

Engine 4 - 2017 Rosenbauer Commander (1500/750) (SN#17484)

Reserve Apparatus

Engine 11 - 2010 Ferrara Inferno (1500/750) (SN# H-4635) (Ex-Engine 1)

Engine 12 - 2010 Ferrara Inferno (1500/750) (SN# H-4636) (Ex-Engine 2)

Engine 14 - 2014 HME (1250/1000/?F) (Ex-General Electric Schenectady)

Rescue - 200? Ford Excursion 4x4 (Ex-Rescue 1)

Station/Assignment Unknown

Marine 1 - Boat

2017 Rosenbauer Commander pumper (1500/750) (SN#17483) (Ex-Engine 3)

2015 Sutphen Monarch pumper (1500/750) (Ex-Engine 1)

2015 Sutphen Monarch pumper (1500/750) (Ex-Engine 2)

2015 Sutphen Monarch SPH100 aerial (2000/300/100' mid-mount platform) (Ex-Truck 1)

2015 Ford F-350 / Wilde Fire walk-around rescue (Ex-Rescue 1)

2012 Rosenbauer Commander pumper (1500/750) (SN#MN13550) (Ex-Engine 3)

2012 Rosenbauer Commander pumper (1500/750) (Ex-Engine 4)

2012 Sutphen Monarch SPH100 aerial (2000/300/100' mid-mount platform) (SN#HS-5123) (Ex-Truck 2)

2010 Ferrara Inferno HD100 aerial (2000/300/100' mid-mount platform) (SN#H-4516) (Ex-Truck 3, ex-Truck 1)

20?? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4 (Ex-Car 122)

20?? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

20?? Ford F 4x4 walk-around rescue

Schenectadyfirefighters.com site

www.schenectadyfirefighters.com

www.schenectadyfirefighters.com

10-75.net SFD Apparatus site

APPARATUS

Station 1 / Headquarters

Built 1981

Engine 1 - 2021 Rosenbauer Commander

Truck 1 - 2021 Rosenbauer Commander (?/?/100' Cobra mid-mount platform)

Rescue 1 - 2021 Ford F-350 4x4 walk-around

Haz-Mat. Unit 1 - 2001 HME Penetrator walk-around (SN#01F00180) (Ex-East Glenville)

Haz-Mat. Unit 2 - 2010 Ford F-350 / Arrowhead walk-in (Ex-Hazmat 1)

Truck 3 (Reserve) - 2019 Rosenbauer Commander (1500/400/78' rear-mount)

Engine 10 (Reserve) - 2018 Rosenbauer Commander (1500/750) (SN#13978)

Car 19 (Chief) - 200? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

(https://dailygazette.com/2015/08/25/0826_RescueRig/)

Car 20 (Assistant Chief) - 200? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

Car 21 (Assistant Chief) - 200? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

Car 22 (Deputy Chief) - 201? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

Car 25 (Maintenance Unit) - 200? Ford F-350 4x4

2005 Ford Excursion 4x4 (Ex-Hazmat 2)

Station 2

Built 1996

Engine 2 - 2021 Rosenbauer Commander

Truck 2 - 2017 Rosenbauer Commander (2000/300/100' mid-mount platform)

Rescue 2 - 200? Ford Expedition 4x4

Station 3

Built 1938

Engine 3

Truck 3 - 2020/21? Rosenbauer Commander (1500/750/75' rear-mount)

Station 4

Built 1904

Engine 4 - 2017 Rosenbauer Commander (1500/750) (SN#17484)

Reserve Apparatus

Engine 11 - 2010 Ferrara Inferno (1500/750) (SN# H-4635) (Ex-Engine 1)

Engine 12 - 2010 Ferrara Inferno (1500/750) (SN# H-4636) (Ex-Engine 2)

Engine 14 - 2014 HME (1250/1000/?F) (Ex-General Electric Schenectady)

Rescue - 200? Ford Excursion 4x4 (Ex-Rescue 1)

Station/Assignment Unknown

Marine 1 - Boat

2017 Rosenbauer Commander pumper (1500/750) (SN#17483) (Ex-Engine 3)

2015 Sutphen Monarch pumper (1500/750) (Ex-Engine 1)

2015 Sutphen Monarch pumper (1500/750) (Ex-Engine 2)

2015 Sutphen Monarch SPH100 aerial (2000/300/100' mid-mount platform) (Ex-Truck 1)

2015 Ford F-350 / Wilde Fire walk-around rescue (Ex-Rescue 1)

2012 Rosenbauer Commander pumper (1500/750) (SN#MN13550) (Ex-Engine 3)

2012 Rosenbauer Commander pumper (1500/750) (Ex-Engine 4)

2012 Sutphen Monarch SPH100 aerial (2000/300/100' mid-mount platform) (SN#HS-5123) (Ex-Truck 2)

2010 Ferrara Inferno HD100 aerial (2000/300/100' mid-mount platform) (SN#H-4516) (Ex-Truck 3, ex-Truck 1)

20?? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4 (Ex-Car 122)

20?? Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4

20?? Ford F 4x4 walk-around rescue

Schenectadyfirefighters.com site

Stations and Apparatus | Schenectady Permanent Fireman's Association

10-75.net SFD Apparatus site

Attachments

Last edited:

SCHNECETADY

The week of October 9-15, 2016 was Fire Prevention Week, an annual public education campaign since 1927, commemorating the Great Chicago Fire of October 8-9, 1871, one of the deadliest blazes in US history. Like most other cities and towns, Schenectady has had its share of fires. Perhaps the most well-known is the 1690 blaze set by the French and Hurons during the Schenectady Massacre, which consumed the frontier village. The other major conflagration is the fire of 1819, which wiped out the business district on the Binnekill, destroyed many early Dutch buildings, and left 200 families without homes. In 1861, the city was to experience the second significant fire of the nineteenth century.

Broomcorn growing along the banks of the Mohawk with the Burr Bridge in the background

Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

In the mid-1800s, Schenectady was growing. Broom making was a major industry in Schenectady County, with Schenectady, Scotia and Glenville responsible for 1,000,000 brooms per year. These brooms were produced from broomcorn, a type of sorghum. The low-lying land and islands of the Mohawk River were fertile grounds for growing this crop. Otis Smith was one of the first to grow broomcorn in the county. He owned 125 acres, and a factory that by mid-century turned out 192,000 brooms and 180,000 whisk brooms (Cheetham, Peg. “Broom Trade Once Swept Schenectady into Spotlight.” Schenectady Union-Star, 22 Apr. 1955.) Unfortunately, on an August afternoon in 1861 that factory, located on the northwest corner of Washington Avenue and Cucumber Alley, was the source of a conflagration that eventually destroyed it.

How the fire started is not entirely clear. A contemporaneous newspaper report describes how a worker at the broom factory may have been at fault: “He had been pitching the roof with a pail of tar. In some way, perhaps in lighting his pipe, the pitch burst into a blaze and spread and ran down to a heap of dried broom stalks as inflammable as guncotton.” (“The Great Fire in August, 1861.” Schenectady Gazette, 20 Dec. 1911.). Claims by some that this occurred on the north end of the building were contradicted by others’ assertions that the fire started at the southwest corner of the building. In any event, the First Dutch Reformed Church bell would have rung out the alarm, along with other church bells and locomotive whistles.

Once it began, the fire, assisted by a strong wind from the northwest, quickly spread from Otis Smith’s factory at the foot of Cucumber Alley to the corners of Church and Washington, and the western end of Front Street. It spread along the western side of Washington to the Mohawk River in the north and extended south, and reached houses on the eastern corners of Front and Washington. In an effort to beat back the fire, residents on the western side of Ferry Street were soaking their wooden roofs with pails of water.

Photo of an early "engine" in Crescent Park. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

Firefighting in the mid-nineteenth century was very different from that endeavor today. After the fire of 1819, the city purchased a piece of equipment called a forcing pump, which has been described by Larry Hart in Volume 1 of Tales of Old Schenectady as “…a tub on wheels (though called an engine) which was fitted with a fixed nozzle and dragged to the scene of a fire like a feeble cannon.” Hauling this cart over cobblestone streets could not have been an easy task for the volunteer firefighters; horses were not used until 1896 because part-time volunteer companies could not look after the animals. Fighting the fire was a bit awkward, as the firefighters had to position the cart correctly in order to aim the hand-pumped stream of water at the flames. The cart was filled with water from cisterns, located at key points in the city, and refilled as necessary. By the 1830s, the city turned to suction pumpers, which replaced the need for bucket brigades in drawing water from the cisterns. One model was the “Button” hand pumper, pulled by a large crew of men, who also had the exhausting job of operating the pump handles. Individual residents still used leather pails to quench fires in their homes.

One can imagine the pandemonium let loose by this catastrophic event. In 1861 the firefighting service had a limited capacity to check the spread of fires. Residents were very concerned, some even panicked, about the ultimate safety of their homes and possessions. Many were dousing their houses with water. Some were conveying their property into the streets. Adding to the chaotic scene was the cacophony of sound, made up of the shouting of firefighters and residents, the clacking of fire engine wheels and the licking of the flames devouring wood. Completing the picture was the chilling sight of buildings ablaze, with the billowing clouds of smoke looming above. Sadly, thieves took advantage of the disorder to ply their trade.

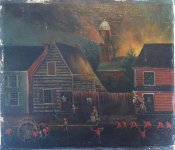

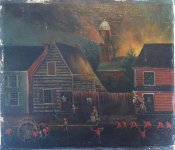

Painting of the 1861 fire that consumed the Dutch Reformed Church. Courtesy of the Schenectady History Museum

In the path of destruction stood the Old Dutch Reformed Church. This brick building, which had a cupola and bell tower encasing a two-ton bell, was constructed in 1814. Among its treasured contents were a very large brass chandelier and an organ. While people were occupied with the danger to their own homes and businesses, the edifice caught fire. Unfortunately, the engines were located near the river, which put them too far away from the church to save it. However, people did their best to salvage whatever they could on the inside, including the pulpit, books, carpets, and a chandelier; the organ was not saved. Ironically, in 1861 the church’s 3,200 pound bell had been in use for only 13 years. It replaced the famously sonorous 1732 bell, which cracked in 1848 and was melted down into miniature bells for the congregants. A local reporter dramatically described the destruction of the steeple and the bell on that afternoon in August of 1861:

“With steady rapidity the work of destruction circled the steeple, till it tottered and fell with a tremendous crash, and spread over the roof till it thundered down. The bell, weighing 3,200 lbs., was eaten away from its supports, and fell, crashing through floors, partitions, and masonry, making more noise in its last moments than it ever made in its life, killed, like a faithful sentinel, by the very enemy whose approach it had heralded.”

(“The Fire of Tuesday.” Evening Star and Times [Schenectady, NY], 9 Aug. 1861, p. 1.)

In an interesting side note, the pastor was reputedly far from distressed by the collapse of the building. On the contrary, the destruction “…was viewed with unconcealed joy by the pastor, who had been struggling and fighting for a new church for years.” (“The Great Fire in August, 1861.” Schenectady Gazette, 20 Dec. 1911, p. 12.).

Although the five volunteer fire companies were making heroic efforts to stem the tide of the flames, it became clear that they needed aid from other locales. In the absence of the mayor, the city’s recorder telegraphed Albany, Troy and Amsterdam for help. All responded, arriving as the fire was dwindling. Extraordinarily powerful at the time was Troy’s steam pumper, the Hugh Rankin. Although situated in Governor’s Lane north of Front Street, it pumped water all the way to Washington Avenue through 15,000 feet of hose. It was reported that the powerful stream destroyed the walls of the building it was targeting. In spite of these efforts, the wind-swept fire did spread to areas farther away. Embers landed on rooftops as far afield as the area around the junction of State Street and Nott Terrace/Veeder Avenue. A building on Nott Terrace was set ablaze, as well as one at 117 South Center Street, near the corner of Franklin Street.

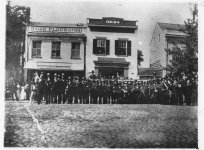

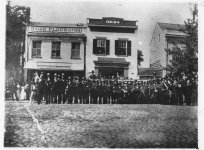

Members of the Protection Hose Company No. 1. located on State Street near South Ferry. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

The cost of the fire was $120,000, which is equivalent to over $3,000,000 today. Although no one died, there was substantial property damage. The Smith factory and warehouse were destroyed, along with ancillary buildings, equipment, and products. The Old Dutch Church was destroyed. Severe damage was done to the western portion of Washington Avenue, particularly heading north to the river; only one building remained standing between the Otis broom shop and the Scotia Bridge at the end of Washington Avenue. Additional damage was done to two houses on Washington Avenue south of Front Street. The eastern corners of Front Street and Washington Avenue were also involved in the blaze, as was Church Street. Destruction was limited by the concerted efforts of residents, who doused buildings with water and, in some cases, knocked down blazing structures to halt the spread of the flames.

Photo showing Cucumber Alley and the Whitmyre Broom Factory. The Dutch Reformed Church can also be seen in the background. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

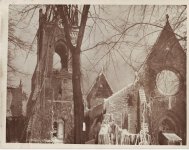

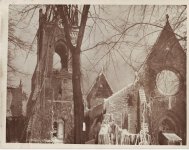

The fire brought changes. The Otis property was purchased by Charles L. Whitmyre, who later built the Whitmyre and Co. Broom Factory on the site. A new stone church was built in 1862, positioned farther away from the front of the street. Sadly, it was the victim of the fire of February 1, 1948 and was once again rebuilt. The fire department replaced hand pumpers with three steam pumpers between 1864 and 1869. These too were replaced in 1872, as the introduction of fire hydrants, as part of a municipal water system, made them obsolete. Toward the end of the century, hand-drawn hose carts gave way to horse power.

The broom factory at Cucumber and Washington would see another blaze in the 1870s. After it became the Whitmyre Broom Factory.

Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

The First/Dutch Reformed Church would also see another destructive fire in 1948. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

The 1861 fire was certainly not the last in the city. With the continual evolution of firefighting techniques and more sophisticated equipment, we will never again witness a conflagration like those of earlier times.

For more information on the fires of 1819 and 1861, see Robert A. Petito Jr.'s excellent article “The Fires of Schenectady,” in the May-June 2011 issue of Schenectady County Historical Society Newsletter.

gremsdoolittlelibrary.blogspot.com

gremsdoolittlelibrary.blogspot.com

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2016

Schenectady's Fire of 1861

This post was written by library volunteer Diane LeoneThe week of October 9-15, 2016 was Fire Prevention Week, an annual public education campaign since 1927, commemorating the Great Chicago Fire of October 8-9, 1871, one of the deadliest blazes in US history. Like most other cities and towns, Schenectady has had its share of fires. Perhaps the most well-known is the 1690 blaze set by the French and Hurons during the Schenectady Massacre, which consumed the frontier village. The other major conflagration is the fire of 1819, which wiped out the business district on the Binnekill, destroyed many early Dutch buildings, and left 200 families without homes. In 1861, the city was to experience the second significant fire of the nineteenth century.

Broomcorn growing along the banks of the Mohawk with the Burr Bridge in the background

Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

In the mid-1800s, Schenectady was growing. Broom making was a major industry in Schenectady County, with Schenectady, Scotia and Glenville responsible for 1,000,000 brooms per year. These brooms were produced from broomcorn, a type of sorghum. The low-lying land and islands of the Mohawk River were fertile grounds for growing this crop. Otis Smith was one of the first to grow broomcorn in the county. He owned 125 acres, and a factory that by mid-century turned out 192,000 brooms and 180,000 whisk brooms (Cheetham, Peg. “Broom Trade Once Swept Schenectady into Spotlight.” Schenectady Union-Star, 22 Apr. 1955.) Unfortunately, on an August afternoon in 1861 that factory, located on the northwest corner of Washington Avenue and Cucumber Alley, was the source of a conflagration that eventually destroyed it.

How the fire started is not entirely clear. A contemporaneous newspaper report describes how a worker at the broom factory may have been at fault: “He had been pitching the roof with a pail of tar. In some way, perhaps in lighting his pipe, the pitch burst into a blaze and spread and ran down to a heap of dried broom stalks as inflammable as guncotton.” (“The Great Fire in August, 1861.” Schenectady Gazette, 20 Dec. 1911.). Claims by some that this occurred on the north end of the building were contradicted by others’ assertions that the fire started at the southwest corner of the building. In any event, the First Dutch Reformed Church bell would have rung out the alarm, along with other church bells and locomotive whistles.

Once it began, the fire, assisted by a strong wind from the northwest, quickly spread from Otis Smith’s factory at the foot of Cucumber Alley to the corners of Church and Washington, and the western end of Front Street. It spread along the western side of Washington to the Mohawk River in the north and extended south, and reached houses on the eastern corners of Front and Washington. In an effort to beat back the fire, residents on the western side of Ferry Street were soaking their wooden roofs with pails of water.

Photo of an early "engine" in Crescent Park. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

Firefighting in the mid-nineteenth century was very different from that endeavor today. After the fire of 1819, the city purchased a piece of equipment called a forcing pump, which has been described by Larry Hart in Volume 1 of Tales of Old Schenectady as “…a tub on wheels (though called an engine) which was fitted with a fixed nozzle and dragged to the scene of a fire like a feeble cannon.” Hauling this cart over cobblestone streets could not have been an easy task for the volunteer firefighters; horses were not used until 1896 because part-time volunteer companies could not look after the animals. Fighting the fire was a bit awkward, as the firefighters had to position the cart correctly in order to aim the hand-pumped stream of water at the flames. The cart was filled with water from cisterns, located at key points in the city, and refilled as necessary. By the 1830s, the city turned to suction pumpers, which replaced the need for bucket brigades in drawing water from the cisterns. One model was the “Button” hand pumper, pulled by a large crew of men, who also had the exhausting job of operating the pump handles. Individual residents still used leather pails to quench fires in their homes.

One can imagine the pandemonium let loose by this catastrophic event. In 1861 the firefighting service had a limited capacity to check the spread of fires. Residents were very concerned, some even panicked, about the ultimate safety of their homes and possessions. Many were dousing their houses with water. Some were conveying their property into the streets. Adding to the chaotic scene was the cacophony of sound, made up of the shouting of firefighters and residents, the clacking of fire engine wheels and the licking of the flames devouring wood. Completing the picture was the chilling sight of buildings ablaze, with the billowing clouds of smoke looming above. Sadly, thieves took advantage of the disorder to ply their trade.

Painting of the 1861 fire that consumed the Dutch Reformed Church. Courtesy of the Schenectady History Museum

In the path of destruction stood the Old Dutch Reformed Church. This brick building, which had a cupola and bell tower encasing a two-ton bell, was constructed in 1814. Among its treasured contents were a very large brass chandelier and an organ. While people were occupied with the danger to their own homes and businesses, the edifice caught fire. Unfortunately, the engines were located near the river, which put them too far away from the church to save it. However, people did their best to salvage whatever they could on the inside, including the pulpit, books, carpets, and a chandelier; the organ was not saved. Ironically, in 1861 the church’s 3,200 pound bell had been in use for only 13 years. It replaced the famously sonorous 1732 bell, which cracked in 1848 and was melted down into miniature bells for the congregants. A local reporter dramatically described the destruction of the steeple and the bell on that afternoon in August of 1861:

“With steady rapidity the work of destruction circled the steeple, till it tottered and fell with a tremendous crash, and spread over the roof till it thundered down. The bell, weighing 3,200 lbs., was eaten away from its supports, and fell, crashing through floors, partitions, and masonry, making more noise in its last moments than it ever made in its life, killed, like a faithful sentinel, by the very enemy whose approach it had heralded.”

(“The Fire of Tuesday.” Evening Star and Times [Schenectady, NY], 9 Aug. 1861, p. 1.)

In an interesting side note, the pastor was reputedly far from distressed by the collapse of the building. On the contrary, the destruction “…was viewed with unconcealed joy by the pastor, who had been struggling and fighting for a new church for years.” (“The Great Fire in August, 1861.” Schenectady Gazette, 20 Dec. 1911, p. 12.).

Although the five volunteer fire companies were making heroic efforts to stem the tide of the flames, it became clear that they needed aid from other locales. In the absence of the mayor, the city’s recorder telegraphed Albany, Troy and Amsterdam for help. All responded, arriving as the fire was dwindling. Extraordinarily powerful at the time was Troy’s steam pumper, the Hugh Rankin. Although situated in Governor’s Lane north of Front Street, it pumped water all the way to Washington Avenue through 15,000 feet of hose. It was reported that the powerful stream destroyed the walls of the building it was targeting. In spite of these efforts, the wind-swept fire did spread to areas farther away. Embers landed on rooftops as far afield as the area around the junction of State Street and Nott Terrace/Veeder Avenue. A building on Nott Terrace was set ablaze, as well as one at 117 South Center Street, near the corner of Franklin Street.

Members of the Protection Hose Company No. 1. located on State Street near South Ferry. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

The cost of the fire was $120,000, which is equivalent to over $3,000,000 today. Although no one died, there was substantial property damage. The Smith factory and warehouse were destroyed, along with ancillary buildings, equipment, and products. The Old Dutch Church was destroyed. Severe damage was done to the western portion of Washington Avenue, particularly heading north to the river; only one building remained standing between the Otis broom shop and the Scotia Bridge at the end of Washington Avenue. Additional damage was done to two houses on Washington Avenue south of Front Street. The eastern corners of Front Street and Washington Avenue were also involved in the blaze, as was Church Street. Destruction was limited by the concerted efforts of residents, who doused buildings with water and, in some cases, knocked down blazing structures to halt the spread of the flames.

Photo showing Cucumber Alley and the Whitmyre Broom Factory. The Dutch Reformed Church can also be seen in the background. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

The fire brought changes. The Otis property was purchased by Charles L. Whitmyre, who later built the Whitmyre and Co. Broom Factory on the site. A new stone church was built in 1862, positioned farther away from the front of the street. Sadly, it was the victim of the fire of February 1, 1948 and was once again rebuilt. The fire department replaced hand pumpers with three steam pumpers between 1864 and 1869. These too were replaced in 1872, as the introduction of fire hydrants, as part of a municipal water system, made them obsolete. Toward the end of the century, hand-drawn hose carts gave way to horse power.

The broom factory at Cucumber and Washington would see another blaze in the 1870s. After it became the Whitmyre Broom Factory.

Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

The First/Dutch Reformed Church would also see another destructive fire in 1948. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection.

The 1861 fire was certainly not the last in the city. With the continual evolution of firefighting techniques and more sophisticated equipment, we will never again witness a conflagration like those of earlier times.

For more information on the fires of 1819 and 1861, see Robert A. Petito Jr.'s excellent article “The Fires of Schenectady,” in the May-June 2011 issue of Schenectady County Historical Society Newsletter.

Schenectady's Fire of 1861

This post was written by library volunteer Diane Leone The week of October 9-15, 2016 was Fire Prevention Week, an annual public educat...

SCHENECTADY

WEDNESDAY, MAY 21, 2014

The Day the Circus Came to Town: Schenectady’s 1910 Circus Fire

|

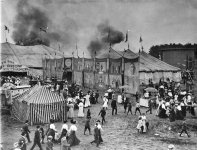

| Crowds exit from a fire in a circus tent at the Barnum & Bailey Circus in Schenectady on May 21, 1910. Image from Grems-Doolittle Library Postcard Collection. |

This blog entry is written by Library Volunteer Mary Ann Ruscitto.

It was May 21, 1910 when a spectacular fire destroyed the main tent of Barnum & Bailey Circus in Schenectady. According to many eyewitnesses, this Saturday afternoon was an afternoon of terror.

Robert Finn was 9 years old in 1910 and claimed that he witnessed how the fire began. Later in his life, he wrote a letter to the Schenectady Gazette with his recollections of the fire. Finn and his father were sitting on the top bench about five feet from where the fire started. They noticed that two men were laughing and joking and when one of the men raised his arm, his cigar touched the canvas and started the fire. Finn’s father grabbed him and they quickly jumped to the ground and got out of the tent. Other people claimed that a boy playing with matches was responsible for the blaze, while still others faulted a careless smoker who tossed a cigarette or match onto paraffin-soaked canvas.

|

| Onlookers watch the blazing Barnum & Bailey Circus tent on May 21, 1910, at the circus grounds in Schenectady. Image from Grems-Doolittle Library Postcard Collection. |

K. H. Schmidt also wrote to the Schenectady Gazette after seeing a story about the fire. In the letter, Schmidt remembered that it was a hot afternoon and he was 8 years old. He went with his grandmother, Emily C. France, to the circus and sat in the reserved section. He states that all at once a large group of workmen could be seen running into the tent yelling, “Fire! Fire! Fire!” And all at once everyone was trying to get out. Many slid down poles that held up the walls of canvas. Schmidt also remembered that the elephants were being lined up for the grand parade entrance into the tent. The animal handlers hurried them down to Van Curler Avenue (at the time, the circus grounds were located where Schenectady High School is today). Schmidt went on to say that in all the confusion, he lost his coat. His mother went to City Hall the next day, where all the personal items that were found at the fire were brought from the fire scene. All was not lost, for this little boy of 8 years old -- when he returned the next year to go to the circus -- still had his ticket stub from 1910 and was able to go for free!

Larry Hart reported in one of his Gazette columns, “For a scant 5 minutes on a May afternoon in 1910 the lives of nearly 12,000 people hung in the balance as the circus tent, which enveloped them, suddenly burst in flames and burned like a mammoth torch.” Miraculously, not one person was killed and only a few were injured.

Hart goes on to say that it was published that the Barnum & Bailey Circus would arrive at the Edison Avenue freight yards at about 4:00 a.m. The customary parade was to leave the circus grounds at 10:00 a.m. The parade route would be down Rugby Road, over Union Avenue and down State Street, then over Church Street and up State Street to McClellan Street and back to the grounds. There were two shows scheduled, one for 2:30 p.m. and the other for 8:00 p.m.

The day did not go well for the circus right from the beginning. One of its circus trains arrived about 1:00 p.m., but it would take nearly 10 hours for the main portion of the big show to finally reach the freight yards. The delay was due to a grass fire along the railroad tracks outside of Rochester, which prevented the circus train from leaving after its last performance. When they finally reached Schenectady, there was difficulty getting the heavy wagons to the grounds due to Edison Avenue being widened and resurfaced. The wagons would be stuck axle-deep in soft dirt. Heavy planking and the elephants were used to pull the wagons out of the dirt with great difficulty. Due to the delay, the traditional circus parade was cancelled.

As the circus tent filled with nearly 12,000 people waiting impatiently for the 2:30 matinee show to begin, the ringmaster announced over his huge megaphone that there would be a slight delay of about 10 minutes before the show would begin. In the mayhem of waiting, someone asked a lady with her child and who had fear written on her face, what is the matter. She replied “Fire!”

Schenectady Gazette columnist Larry Hart went on to report that if it were not for the heroic efforts of Police Chief James W. Rynex, who was at the circus, the fire could have been disastrous. Rynex quickly brought together the dozen uniformed police officers that were on the scene, and recruited about 20 civilians to help maintain order. Chief Rynex’s rapid response helped keep the crowd calm, while at the same time exiting the people very quickly from the burning tent. It took 4 minutes after the first cry of fire to evacuate the tent of nearly 12,000 people.

|

| Fire Chief Henry Yates responded to Schenectady's 1910 circus fire. This photograph of him dates from around 1905. Image from Larry Hart Collection. |

Animal trainers herded up uncaged creatures out of the animal tent to a distant lot far away from the fire scene. The trapper bell sounded in Station 6 at Eastern Avenue and Wendell Avenue at 2:48. In less than 2 minutes, the horse-drawn steamer from the fire station pulled into the circus grounds. Deputy Fire Chief August Derra was in charge of firefighters at first; Fire Chief Henry Yates then took over. The entire top of the tent was consumed in flames. The blaze was extinguished by 3:15, and the all-clear signal came an hour later.

To show its gratitude to the Schenectady Fire Department for its quick and efficient response to the fire, the Barnum & Bailey Circus gave Fire Chief Henry Yates the pick of the fire draft horses that pulled the circus wagons. The horse that was picked was assigned to Fire Station 3 on Jay Street; appropriately, they named him Circus.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2019

200th Anniversary of The Great Fire of 1819

This post was written by library volunteer Gail DenisoffNovember 17, 2019 marks a rather grim anniversary for Schenectady. Two hundred years ago on that day was the Great Fire of 1819, one of the most destructive events in the history of the city. The fire started around 4AM in the currying shop (tannery) of Isaac Haight on the corner of Water and Railroad Streets. A fierce southeast wind fueled the fire and soon the entire block was engulfed. As the wind blew throughout the day, the fire raged, jumping from one street to another, eventually burning the west end of the city between State Street and the Mohawk Bridge including most of Union, Church, Washington, and Front Streets. The bridge also caught fire, but firefighting efforts eventually saved it.

In all, 169 buildings burned, 150 families, many poor people lost their homes, and most of the city business district was destroyed. Damages exceeded $150,000 ($2.7 million today). More details about this fire can be found in a previous post: "The Most Destructive We Have Ever Witnessed": Schenectady's Great Fire of 1819.

At the time of the fire, firefighting techniques were quite primitive in the city. Schenectady had two fire engines and both were unserviceable. Each residence was required to possess a leather fire bucket. When a fire broke out and the signal sounded, the buckets were expected to be put out by the front door and fire fighters would run down the streets collecting buckets and form a bucket brigade from nearby wells or the river. The sheer force of the Fire of 1819, the strong winds and overwhelming size of the fire made this nearly impossible and firefighters focused on saving the bridge. Neighbors and Union College students helped people to save what they could from their homes. Miraculously, no lives were lost, but “many persons were much injured and bruised” according to an article in The Cabinet, a Schenectady newspaper from that time.

The cause of the fire was unknown. For lack of a better reason, it was commonly attributed to spontaneous combustion. According to The Cabinet, building ruins and cellars continued to smolder for days after. The proprietor of the Albany Gazette visited the site and reported:

“The ruins present a most melancholy and awful scene of ruin and desolation; and the personal distress of many of the sufferers is great beyond description – widows and orphan children and many others, who were in the possession of respectable property, and in the enjoyment of most of the conveniences of life, are reduced to wretchedness, to penury and want, and their forlorn situation at the present season makes an irresistible appeal to the sympathy, the benevolence, and charity of their fellow citizens.”

Another observer wrote in a local guidebook that “Schenectady was desolate, stripped of its livelihood and resources. Wharves were deserted, warehouses boarded up, transportation stalled and morale evaporated.”

Fellow citizens of Schenectady and surrounding areas stepped up to aid those suffering from their losses. The Cabinet reported that no more than seven buildings were insured. No insurance companies represented Schenectady and few people could afford to purchase coverage from Albany agencies. One shop was reported to have insured their inventory but not their building. As a result, most everyone affected needed assistance of some sort.

People from surrounding towns, especially Glenville, poured into the city bringing provisions to the fire victims. Loads of lumber came in to help build temporary residences. The Niskayuna Shaker community did as much as possible to aid the many poor who lost everything. Jeremiah Fuller dispensed freely from his large storehouse of grain for horses and livestock.

More formal assistance was soon needed and a meeting of citizens was held headed by David Tomlinson and Joseph C. Yates to solicit donations to aid the victims. The Common Council of Schenectady met numerous times in the aftermath. The minutes from these meetings detail forming committees to address the myriad of issues caused by the fire. A committee was formed to draw up a plan for the collection and distribution of funds for the relief of the suffering. The clerk of the board was asked to notify the Mayors of Albany and Troy that committees would be appointed to make collections in those cities.

Another committee was recommended "whose duty it shall be to ascertain the relative losses and wants of all the individuals who have suffered by the late fire and also to receive and distribute among the sufferers in proportion to their losses and their wants all monies and other contributions that may be received." Despite some victims expecting funds to be evenly distributed, assurance was given the public that they would be used to support the poor during the winter. The council adopted a resolution because "an erroneous impression had been received by the public that the collections made for the sufferers by the late fire in this City are to be distributed among them generally without any regard to their wants.” Another committee was assigned the job of procuring temporary accommodations for sufferers from the fire who had no other place to go and still another committee was named to ascertain the number of buildings destroyed.

A report of the fire along with a call for donations from the Mayor and alderman of the city was published in the Albany Gazette on November 25, 1819 and other newspapers around the state:

"... thus in a few hours, forty nine dwelling house, many inhabited by two and three families and seventy five stores and other buildings of consequence have been utterly destroyed, and their miserable inhabitants, with the commencement of a long and dreary winter turned into in the streets without shelter, and in many instances without furniture, without clothing and without bread, or the methods of procuring either, for such was the rapidity with which the flames spread, that a remnant only of movable articles could be removed and much even of that remnant was again overtaken and afterwards consumed by the devouring element. Under these circumstances the doors of those citizens whose dwellings were mercifully spared, have been flung open to the suffered, and subscriptions are raising throughout the city for their relief. But no effort within the reach of that portion of the inhabitants, who have escaped the common calamity, can meet the exigencies of the case. The local authors are therefore constrained by the sight of miseries too extensive for them to relive, to tell to other cities the tale of woe, and solicit their cooperation. To this end they have appointed the Rev Dr. Andrew Yates, Abraham Van Eps, and Nicholas F. Beck Esqs. as their agents to represent the necessities of the sufferers in this place, and to solicit, and gratefully to receive any benefactions that the charitable in your city may be disposed to bestow.”

Donations came from as far away as New York City. The Park Theater performed a play on the night of November 24 as a fundraiser and several influential business leaders held a meeting to aid the “poor and distressed inhabitants of the city of Schenectady, who have suffered by the fire, which has lately destroyed a great portion of that city.” In a letter dated December 24, Henry Yates Jr., Mayor of Schenectady, wrote to Henry Rutgers, one of the organizers of the fundraiser thanking him for the donation of $3,764 (over $62,000 in today's dollars) collected by the citizens of New York City.

In addition to trying to assist the victims of the fire, the Common Council also addressed the urgency to reorganize the city's fire fighting service as well as provide desperately needed equipment for the fire companies. Minutes from a special meeting held the day of the fire report the Council authorized the employment of 16 watchmen at a fee of one dollar each to watch for fires in the western portion of the city between the hours of 6 PM to 7 AM. They also authorized repairs to the existing hooks and ladders. At a meeting held on December 4th, a committee was appointed to "digest a plan of a new organization of firemen" and on December 8th another committee was named to ascertain the expense of buying a forcing pump or engine. At a meeting on December 11 this committee reported the acquisition of a forcing pump was practical and a new committee was named to select suitable persons to form hook and ladder and axe companies. On December 18 a number of appointments to the fire companies were made and additional appointments were made at a meeting on January 1, 1820. On January 22 the committee authorized to inquire into the cost of a forcing pump was empowered to buy one costing not more than $560 exclusive of hose and carriage "to be made after the model of the engine in Albany". On July 1 the Council adopted a resolution that all the fire engines should not leave the city at the same time without authorization.

Schenectady struggled to rebuild after the fire. With the completion of the Erie Canal by 1825 the business district moved several blocks east. Building boomed and Schenectady soon became an important manufacturing, transportation and trade center.

THURSDAY, JULY 24, 2014

"The Most Destructive We Have Ever Witnessed": Schenectady's Great Fire of 1819

This blog entry is written by Library Volunteer Victoria Bohm.Throughout its 350-plus years of history, Schenectady has had its fair share of destructive fires. Like most cities grown from colonial times built for the most part of wood, the threat of fire was familiar and inevitable. The lack of building codes and standards and zoning laws only enhanced that threat.

The great fire of 1819 was a particularly destructive event in Schenectady’s history. Firefighting -- its techniques, equipment, and manpower -- was still fairly primitive. The wooden structures creating the crowded, unregulated urban sprawl were an architectural tinder box wanting only that first spark. On November 17, 1819, between the hours of 4:00 and 5:00 in the morning, that spark was ignited in Isaac Haight’s currying shop on Water Street. By the time the fire was finally out, most of the city between State Street and the Mohawk Bridge (itself barely saved) lay in ashes. It was one of the worst disasters since the Massacre of 1690.

|

| Len Tantillo's painting Schenectady Harbor renders the city as it may have looked in 1814, just a few years before many of Schenectady's buildings were destroyed by fire. |

The winds were definitely a major factor in 1819; the fire quickly jumped to John Moyston’s home and store, on the opposite side of the street from Mr. Haight's currying shop, and went almost immediately out of control. From there, adjoining buildings were quickly engulfed in the flames. As the stiff south-easterly wind swept the fire along, many buildings in the city between State Street and the Mohawk River burned to the ground; the pitiful remains smoldered on for days.

Injury to the firefighters and to all those who put themselves in harm’s way to help those directly threatened and affected, their persons and their possessions, was severe. About 160 buildings, including homes, storefronts, offices, barns, and other outbuildings, were simply destroyed, along with most of the personal property in them. Trees, grain supplies, and other provisions were destroyed. An article in the Schenectady Cabinet following the fire estimated the damage at over $150,000.00 (over $2.7 million today). Water Street, State Street, Church Street, Union Street, Washington Street, and Front Street all suffered massive damage. Fortunately, not one life was lost in the blaze. Those left homeless had to look to friends, relatives, and charity for help. Union College students were among the largest group who came to the aid of those in need, in helping to protect homes from being burned and in assisting those suffering from the losses after the fire. The town of Glenville started a succession of regional aid actions to bring the basic necessities to the victims, especially those who escaped with only the clothes on their backs in frigid November weather. The region’s Shaker Communities also stepped up to offer aid and comfort, and David Tomlinson and Joseph C. Yates headed up a relief drive in Schenectady.

Schenectady in 1819 had only two fire trucks which, given the scope of the fire coupled with the wind and weather, proved almost useless. There were neither the material resources nor the technology to battle such a fire. And, it was later discovered that the winds had blown bits of burning shingles and other materials as far away as Charlton, a distance of about nine miles! Attempting to save personal property, even with so many able bodies, including the students from Union College, also proved for the most part futile. The best solution found with spur-of-the-moment desperation, was to heave furniture and other items onto any available flat-bottom boat and float out into the middle of the Mohawk River and stay along the banks to which the fire did not reach. The smoldering aftermath revealed yet another sad fact; very few of the buildings destroyed were in any way insured.

Jonathan Pearson’s History of the Schenectady Patent cites the 1819 fire as a catalyst for bringing in a newer, more modern style of architecture as the city rebuilt itself, specifically the English style replacing the original Dutch style. In his 1902 book Schenectady County, New York: Its History to the Close of the Nineteenth Century, author and historian Austin Yates claimed that no truly official documented historical record was ever made regarding the 1819 fire, and that most information about the fire came from eye-witness accounts jotted down before the witnesses died out. Yates then offered another re-telling of those extant descriptions collected through the years for articles and books.

Grems-Doolittle Library Collections Blog

gremsdoolittlelibrary.blogspot.com

gremsdoolittlelibrary.blogspot.com

Grems-Doolittle Library Collections Blog

SCHENECTADY

A recent Times Union article (which you can find here) got us thinking about some of the major winter fires in Schenectady County and the firefighters who braved the cold and icy conditions to extinguish these chilly conflagrations. We searched through our photo archives to look for photos of fires in the wintertime these are a few of the images we found.

gremsdoolittlelibrary.blogspot.com

gremsdoolittlelibrary.blogspot.com

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2019

Fighting Fire in the Wintertime

A recent Times Union article (which you can find here) got us thinking about some of the major winter fires in Schenectady County and the firefighters who braved the cold and icy conditions to extinguish these chilly conflagrations. We searched through our photo archives to look for photos of fires in the wintertime these are a few of the images we found.

|

| One unexpected benefit of the Erie Canal was that having the canal running through the city gave firefighters easier access to a body water to pump for extinguishing fires. The quality of this water may not have been the best (see our previous blog post, The Odors of the Erie in Schenectady) but it was a much needed source of water before the invention of fire hydrants. Courtesy of the Grems-Doolittle Library Photo Collection. |

Grems-Doolittle Library Collections Blog

Schenectady sure has a lot of new equipment, even their reserve fleet is significantly less than 10 years old. Any idea where they got the key huge influx of money?

Schenectady gets four new fire apparatuses

SCHENECTADY, N.Y. (NEWS10) — The Schenectady Fire Department has four new fire apparatuses—two engines, a truck, and a rescue vehicle. On Wednesday, Mayor Gary McCarthy officially commissioned all …

- Joined

- Feb 27, 2010

- Messages

- 1,332

Engine 1 on the photo lineup is a Sutphen, not a Rosenbauer as marked.

SCHENECTADY

Schenectady Fire Department members are represented by IAFF Local 28

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

SCHNECETADY FIRE DEPARTMENT MEMORIAL

SCHNECETADY FIRE DEPARTMENT LINE OF DUTY DEATHS

5/10/1939 FF EDWARD R. BROELAND

1/1/1948 FF HAROLD J. BRAZELL

9/9/1952 FF JOHN M. KILLION

12/13/1960 FF NORMAN LESTER

6/12/1961 FF THOMAS L. SHERIDAN

2/7/1966 CAPT WILLIAM B. BRAZELL

4/19/1966 FF DONALD A. COLLINS

1/11/1974 INSPECTOR JOHN DOMBLEWSKI

3/20/1975 CAPT EDWARD KEARNEY

3/26/1975 FF EDWARD R. SKUMURSKI

Schenectady Fire Department members are represented by IAFF Local 28

Schenectady Firefighters

Schenectady Firefighters. Отметки "Нравится": 4 308. http://www.schenectadyfirefighters.com/

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

SCHNECETADY FIRE DEPARTMENT MEMORIAL

SCHNECETADY FIRE DEPARTMENT LINE OF DUTY DEATHS

5/10/1939 FF EDWARD R. BROELAND

1/1/1948 FF HAROLD J. BRAZELL

9/9/1952 FF JOHN M. KILLION

12/13/1960 FF NORMAN LESTER

6/12/1961 FF THOMAS L. SHERIDAN

2/7/1966 CAPT WILLIAM B. BRAZELL

4/19/1966 FF DONALD A. COLLINS

1/11/1974 INSPECTOR JOHN DOMBLEWSKI

3/20/1975 CAPT EDWARD KEARNEY

3/26/1975 FF EDWARD R. SKUMURSKI

SCHENECTADY

www.cityofschenectady.com

www.cityofschenectady.com

STEPS TO BECOMING A SCHENECTADY FIREFIGHTER

EDUCATION: (required at time of appointment)

60 college credits (credits from paramedic school can be applied to the 60 required credits), New York State Paramedic Certification (HVCC and Cobleskill both have a Paramedic Program)

CIVIL SERVICE EXAM:

You must take and pass a written exam administered by Schenectady County Civil Service commission. The test is administered approximately every 2 years. After the test is given an eligibility list is established for those candidates that meet all the requirements. Preference may be given to residence of the City of Schenectady. You won’t be eligible to be hired until the educational portion is complete, but you are still eligible to take the civil service exam.

You may go to the Schenectady County Civil Service Commission any time during normal business hours. They are located in the County Office building at 320 State St. Schenectady, NY on the second floor. You can also call and ask when the next firefighter exam will be offered at (518) 388-4233, visit schenectadycounty.com or Google search Schenectady County Civil Service Commission.

Check in with Civil Service regularly to find out about upcoming exams. There is a very specific timeline as to when you must apply. You don’t want to miss any deadlines.

CANDIDATE PHYSICAL ABILITY TEST (CPAT):

To be eligible for appointment to the Schenectady Fire Department all candidates must take and pass a CPAT test. This will test your ability to perform the required tasks to be a firefighter. This test consists of 8 separate events and are performed in a row and timed. The events are: stair climb, hose drag, equipment carry, ladder raise and extension, forcible entry, search, rescue and ceiling breach and pull.

Detailed information will be given to eligible candidates prior to the CPAT test date. In the meantime the best way to prepare for this is by doing regular strength and cardio conditioning exercises. This test will be provided by the fire department.

MEDICAL EXAM:

It is a condition of employment that all candidates successfully pass a medical exam which follows the specifications of the NFPA (National Fire Protection Association). This exam will be provided by the Fire Department prior to appointment. You do not have to go and take this on your own.

Recruitment | Schenectady, NY

RYE The Rye Fire Department is a combination department consisting of both volunteer and career firefighters. The Department is broken down into four fire companies: Poningoe Hook and Ladder, Poningoe Engine and Hose, Milton Point Engine and Hose and the Rye Fire Police Patrol. The Poningoe Hook and Ladder Company and Poningoe Engine and Hose Company are located out of Rye Fire Headquarters at 15 Locust Avenue. The Milton Point Engine and Hose and the Rye Fire Police Patrol are located at the Milton Point Firehouse (Station 2) at 560 Milton Road. Together, the Rye Fire Department responds to approximately 1000 calls per year. Poningoe Hook and Ladder Company - At fire scenes, members of the H&L are primarily responsible for forcible entry, location of the fire (if not already known), search and rescue, ladder operations, ventilation, salvage and overhaul. H&L apparatus include two Seagrave 100' Rearmount Ladders: Ladder 25, a 2007 model and Ladder 26, a 2001. Poningoe Engine and Hose Company - At fire and accident scenes, members of the Hose Company are primarily responsible for extinguishing the fire and obtaining a source of water to sustain fire fighting operations. In motor vehicle accidents, the engine and hose members are also responsible for extrication. Poningoe E&H apparatus include Engine 191, a 1994 Pierce Lance Rescue Pumper. Milton Point Engine and Hose Company - Milton Point E&H responsibilities mirror the responsibilities of the Poningoe E&H including obtaining a water source, fire extinguishing, and vehicle extrication. Milton Point E&H apparatus include: Engine 192, a 2006 Seagrave Pumper and Engine 193, a 1987 Sutphen Pumper. Rye Fire Police Patrol - At fire and accident scenes, exterior members of the Fire Police Patrol run traffic operations, scene control, salvage, lighting, and other support functions. The interior members of the Fire Police Patrol assist the Engine and Ladder Companies. The Rye Fire Police Patrol's primary apparatus is Utility 39, a 1989 International/Saulsbury Generator/Light truck. Utility 49, a 2006 Chevrolet Silverado pickup truck, is also kept at the Milton Firehouse. All firefighters are cross-trained regardless of their Company affiliation. In other words, a Ladder Company member might advance a hoseline while an Engine Company member is involved in roof operations. This ensures the highest level of readiness so we can fully protect the citizens of Rye and their property.  Emergency Services Fire suppression service Control of hazardous material incidents Accident victim extrication Public safety education Vehicle extraction Building collapse Flood evacuation Security of utility services during floods of utility company emergencies until the arrival of emergency crews from the utility company and all other natural disorders Marine fire protection Assistance to other agencies for search & rescue Assistance to other agencies for emergency electric power Assistance to other agencies for traffic control Mutual aid assistance to other communities Provides Fire prevention programs and activities Building lock-out/lock-in assistance Fire Stations  Fire Headquarters Poningoe Engine & Hose Co. 1 / Poningoe Hook & Ladder Co. 1 15 Locust Avenue  Engine 191 - 2020 Seagrave Marauder (1500/750) (SO#78K09)  Ladder 25 - 2007 Seagrave Commander II low-profile (100' rear-mount)  Utility 39 - 1989 International S / Saulsbury walk-around rescue (Ex-Patrol 3)  Car 2421 (Chief) - 2010 Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4  Car 2422 (Assistant Chief) - 2014 Ford Police Interceptor Utility  Car 2424 (Deputy Chief) - 2006 Chevrolet Tahoe 4x4  Car 2425 (Deputy Chief) - 2007 Ford Crown Victoria  Fire Station 2 / Milton Point Engine and Hose Co. 1 / Rye Fire Police Patrol Co. 1 560 Milton Road  Engine 192 - 2006 Seagrave (1500/500/30F)  Engine 193 - 1994 Pierce Lance (1500/750/30F) (Ex-Engine 191)  Utility 49 - 2006 Chevrolet Silverado 4x4  Retired Apparatus2001 Seagrave aerial (100' rear-mount) (Ex-Ladder 26)1992 Ford F-150 4x4 1987 Sutphen pumper (1500/500) (Ex-Engine 193) 1985 Spartan / 1955 Maxim aerial (85' tractor-drawn) (Ex-Ladder 26) 1982 Hahn pumper (1500/500) (Donated to Westchester County Fire Training Center) (Ex-Engine 194) 1975 Seagrave aerial (100' tractor-drawn) (Ex-Ladder 25) 1966 Maxim F pumper1966 Maxim S pumper 1964 Maxim F lighting unit1962 Maxim S pumper 1955 Maxim aerial (85' tractor-drawn) (Tiller remounted on a 1985 Spartan tractor) 1950 Ward LaFrance pumper1948 Dodge lighting unit 1947 Mack 45 pumper 1929 Seagrave aerial (75' tractor-drawn) 1927 Mack Bulldog pumper 1914 Mack chemical engine 1902 Hose Wagon1892 Button Hand pump 1887 Ladder truck 1887 Hose cart

Rye Fire Department (New York)All pump/tank measurements are in US gallons. Poningoe Engine & Hose Co. 1 / Poningoe Hook & Ladder Co. 1 Ladder 25 - 2007 Seagrave Commander II low-profile (-/-/100' rear-mount) Utility 39 - 1989 International S / Saulsbury walk-around rescue (Ex-Patrol 3) Engine 191 "Garnet Pride" - 2020...

|

RYE

In 1660 a small group of settlers including Peter Disbrow, John Coe and Thomas Studwell landed at Manursing Island, where they met the Poningoe Indians and purchased much of the land that is now the City of Rye.

The earliest records of Rye Volunteer Firefighters date back to 1886 when the Poningoe Fire Company was formally organized. Firefighting equipment included a hand–drawn engine and a small hose cart. The apparatus was stored in James Cushion’s blacksmith shop, now the site of the Rye Commons Apartments on the Boston Post Road (across from City Hall.) The Rye Fire Department was formally organized in 1892.

In October of 1902, the Milton Point Hose Company was formed. The company was granted the use of a building known as the John Weed Store, on property adjacent to the Rye Municipal Boat Basin that would later be home of the Brailsford Company, and is now a private residence. On January 1, 1903 the Milton Company was officially made part of the Rye Fire Department. Historical records note that keys and badges were supplied to the members for $.85.

Rye has always been diligent in adopting the newest equipment to protect its citizens and their property. In 1903 the Milton company received a hand pump that included leather water buckets.

In 1905, then Mayor Theodore Fremd formed the Fire Police Patrol Company, which shared the Milton Point station. Mayor Fremd would become the first Captain of the Rye Fire Police.

In 1907, Mrs. William Parsons offered a piece of land on Locust Ave to act as the Headquarters for the Department. Upon receipt of the land the taxpayers approved $40,000 to build the headquarters. The building was state of the art including an auditorium, two meeting rooms, engine room, and stables to accommodate six horses. The house had the latest in technology including ridged concrete flooring designed to keep the horses from slipping as they started to pull the heavy fire engine.

As the Milton Point area continued to grow, it was clear that a new building to house the Milton Point Hose Company and Fire Police Patrol was needed. On Nov. 6, 1912, both companies moved into the present location on Milton Road.

Early to adopt mechanized technology, Rye purchased their first motor driven apparatus, a 40 hp Locomobile, in 1914. It was customized to address the needs of the department and included ladders, 1000 feet of hose, and several small chemical extinguishers. Alfred Gedney, our first career professional, was appointed as caretaker and driver of the apparatus.

In 1986, the Department celebrated its 100th anniversary. The event was commemorated with a parade through downtown featuring 54 departments and over 300 pieces of apparatus.

At the turn of the 20th to 21st centuries, Rye's two firehouses were showing their age and in need of structural repair and updated facilities and equipment in order to comply with NFPA, OSHA and ADA requirements. Rye taxpayers approved a bond issue that provided the capital needed to improve and expand both houses. On May 17, 2008 a public open house was held at the newly renovated Headquarters building, officially marking the completion of the project.

History of the Rye Fire Department

In 1660 a small group of settlers including Peter Disbrow, John Coe and Thomas Studwell landed at Manursing Island, where they met the Poningoe Indians and purchased much of the land that is now the City of Rye.

The earliest records of Rye Volunteer Firefighters date back to 1886 when the Poningoe Fire Company was formally organized. Firefighting equipment included a hand–drawn engine and a small hose cart. The apparatus was stored in James Cushion’s blacksmith shop, now the site of the Rye Commons Apartments on the Boston Post Road (across from City Hall.) The Rye Fire Department was formally organized in 1892.

In October of 1902, the Milton Point Hose Company was formed. The company was granted the use of a building known as the John Weed Store, on property adjacent to the Rye Municipal Boat Basin that would later be home of the Brailsford Company, and is now a private residence. On January 1, 1903 the Milton Company was officially made part of the Rye Fire Department. Historical records note that keys and badges were supplied to the members for $.85.

Rye has always been diligent in adopting the newest equipment to protect its citizens and their property. In 1903 the Milton company received a hand pump that included leather water buckets.

In 1905, then Mayor Theodore Fremd formed the Fire Police Patrol Company, which shared the Milton Point station. Mayor Fremd would become the first Captain of the Rye Fire Police.

In 1907, Mrs. William Parsons offered a piece of land on Locust Ave to act as the Headquarters for the Department. Upon receipt of the land the taxpayers approved $40,000 to build the headquarters. The building was state of the art including an auditorium, two meeting rooms, engine room, and stables to accommodate six horses. The house had the latest in technology including ridged concrete flooring designed to keep the horses from slipping as they started to pull the heavy fire engine.

As the Milton Point area continued to grow, it was clear that a new building to house the Milton Point Hose Company and Fire Police Patrol was needed. On Nov. 6, 1912, both companies moved into the present location on Milton Road.

Early to adopt mechanized technology, Rye purchased their first motor driven apparatus, a 40 hp Locomobile, in 1914. It was customized to address the needs of the department and included ladders, 1000 feet of hose, and several small chemical extinguishers. Alfred Gedney, our first career professional, was appointed as caretaker and driver of the apparatus.

In 1986, the Department celebrated its 100th anniversary. The event was commemorated with a parade through downtown featuring 54 departments and over 300 pieces of apparatus.

At the turn of the 20th to 21st centuries, Rye's two firehouses were showing their age and in need of structural repair and updated facilities and equipment in order to comply with NFPA, OSHA and ADA requirements. Rye taxpayers approved a bond issue that provided the capital needed to improve and expand both houses. On May 17, 2008 a public open house was held at the newly renovated Headquarters building, officially marking the completion of the project.

Last edited:

RYE

The Rye Professional Firefighters are made up of a 20 member local who have been serving the people of Rye since 1919. Originally hired to provide the fire department with a staff of drivers, the job has evolved with the growing demands and needs of the community. As the population and demographics of Rye have changed over the years, our membership has been dispatched on an increasing number of alarms.

Local 2029 is a member of the International Association of Firefighters, AFL-CIO.

As early as 1919, the Rye Fire Department employed Career Firefighters to serve as drivers. Since then, the City has hired a total of 58 Career Firefighters. Our latest hire was in September of 2022.

www.local2029.com

www.local2029.com

Rye Professional Firefighters Association

IAFF Local 2029

Is a 21 member local who have been serving the people of Rye since approximately 1919 early records show. Originally hired to provide the fire department with a staff of drivers, our job has evolved with the growing demands and needs of the community. Within the Rye Profesional Firefighters Local 2029 are 20 Career Firefighters and 1 Career Fire Lieutenant, who also serves as the City of Rye Fire Inspector. The career and volunteer firefighters work together at a scene of an emergency to assist and help the public.

In the history of the career staff there have been 50 members with 20 currently employed by the City of Rye. Our first career firefighter was hired around 1919, and our most recent hiring was made in Sepember of 2017.

24 Hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year, there are four career firefighters at Headquarters, staffing both Engine 191 and Ladder 25 . There is one career firefighter assisnged to the Milton Fire Station to staff Engine 192. The Career Fire Lieutenant/Fire Inspector responds to all calls when available and on duty, using the identifier Car 2421. The Career Fire Lieutenant/Fire Inspector will serve as the incident commander.

The Rye Professional Firefighters are made up of a 20 member local who have been serving the people of Rye since 1919. Originally hired to provide the fire department with a staff of drivers, the job has evolved with the growing demands and needs of the community. As the population and demographics of Rye have changed over the years, our membership has been dispatched on an increasing number of alarms.

Local 2029 is a member of the International Association of Firefighters, AFL-CIO.

As early as 1919, the Rye Fire Department employed Career Firefighters to serve as drivers. Since then, the City has hired a total of 58 Career Firefighters. Our latest hire was in September of 2022.