You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

23rd Street Collapse

- Thread starter 1261Truckie

- Start date

When I was a proby in E5, there was a member that was a proby at that fire. He was instructed to remain at the top of the stairs, as the rest of the company entered the cellar. After a short time, he observed papers and debris being sucked down the stairs. Not sure what was happening he shouted to all members to get out of the cellar. As at least 2 companies L3 and E5 raised up the stairs as the fire roared over their heads. He saved many more from sure death. Unfortunately he is no longer with us. RIP to all!

- Joined

- Nov 2, 2020

- Messages

- 1,327

It seemed that 99% of engine companies from the Battery to Midtown had those '54 Macks. My dad loved that rig.

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2007

- Messages

- 1,620

Rest in Peace, Nick

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2007

- Messages

- 1,620

L-132 had two former members of L-3 assigned as Lieutenants. One of them, PC, was working in E-5 that night on a 30 day detail prior to his promotion to Lieutenant. He told us Nick's story. Indeed the FDNY could have lost more that night. Never Forget.

The one drawback with the 54 Mack was that it didn’t have a booster tank. So either you had to hook up to a hydrant or a hose directly off the hydrant for all rubbish fires. Then in 1969 they had to cover the cab and back step with wood to protect the members.

- Joined

- Nov 2, 2020

- Messages

- 1,327

I recall Pop telling me that at certain boxes north of 16's quarters if they saw an auto or rubbish he sort of eased up on the gas so 21 engine would get in first and hit it with the booster. 21 had a Ward LaFrance at the time. lolThe one drawback with the 54 Mack was that it didn’t have a booster tank. So either you had to hook up to a hydrant or a hose directly off the hydrant for all rubbish fires. Then in 1969 they had to cover the cab and back step with wood to protect the members.

- Joined

- Nov 2, 2020

- Messages

- 1,327

Probably not Loo. He retired in '58 when they were still on 25th street.E5 did the same thing with E28, and we would ask them if they would use their booster. I’m sure there were times I worked with your Pop when I got detailed to 29th street.

- Joined

- May 6, 2010

- Messages

- 17,548

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BOX 598 10-17-66

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

October 12, 2003

A Grievous Day, Eclipsed by Sept. 11

By ROBERT F. WORTH

On Oct. 17, 1966, 12 firefighters died while responding to a catastrophic fire across Broadway from the Flatiron Building. For 35 years, the tragedy remained the New York Fire Department's single greatest loss of life.

For more than two decades, the city marked the anniversary with a solemn ceremony. But in the early 1990's, several years before Oct. 17 was eclipsed by Sept. 11 as the saddest date on the firefighters' calendar, memories began to dim, and the city stopped holding memorial services for those 12 dead men.

The terrorist attack is still an open wound. Flowers and candles can still be seen in front of firehouses that lost men, and ground zero remains a somber pilgrimage site. T-shirts proclaim that we will "never forget."

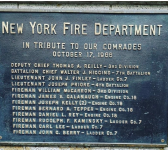

But we do forget. Like many before it, the '66 fire has begun fading into history. All that now remains at the site, a high-rise on East 23rd Street facing Madison Square Park, is a small bronze plaque with the date and the names of the dead.

Calamities cry out for attention every day, and the sad truth is that huge numbers of casualties trump small ones. So it is not surprising that the loss of 343 firefighters on Sept. 11, 2001, has dwarfed every other Fire Department tragedy.

A small group of firefighters and relatives still gather on the anniversary of the '66 fire. A few have vowed to bring it back to the city's consciousness. But they know that time and totals are against them.

"When I started hearing the numbers after Sept. 11, I said to myself, `Well, 12 is nothing now,' " said Manuel Fernandez, who lost all but one of six fellow firefighters in Engine 18 in the '66 fire. "But that shouldn't mean we forget these guys. Twelve men never came home. And it meant a lot to the city at the time."

Mr. Fernandez has been urging city officials to revive a formal commemoration. As of now, there are no plans to do so, said the Fire Department's chief spokesman, Francis X. Gribbon.

"Unfortunately," he said, "there have been so many tragic losses in recent history that it would be hard to honor them all separately."

Photographs from the '66 fire eerily foreshadow the images of Sept. 11. Thousands of haggard firefighters gathered at the scene as the dead were carried out of the blackened building. Thousands more lined Fifth Avenue during the funeral cortege four days later. The heroism of the dead men was proclaimed in headlines for weeks afterward.

"It really stopped New York City," said Daniel Andrews, who at the time followed Engine 18 as a teenage fire buff and now works in the Queens borough president's office. "You could hear a pin drop on Fifth Avenue during those funerals."

It all began on a cool evening at 9:30 p.m. Mr. Fernandez, a former professional boxer who had been with Engine 18 on West 10th Street for six years, was upstairs in the kitchen eating a late supper when he heard the first alarm.

When Engine 18 arrived at 23rd Street and Broadway, several crews were already on the scene. Smoke was rising from one of the buildings along Broadway, but no flames were visible, and the firefighters were confused about the source of the fire.

"I dropped them off on the 23rd Street side, and it was hazy in there, like a pool room," Mr. Fernandez said. As the "chauffeur," his duty was to man the motor pump on the engine.

While on the street, he heard a dull roar and knew instantly that something was wrong. He went into the drugstore building where five of his fellow firefighters had gone and began crawling in darkness. "You had about a foot of clear vision," he recalled. "I'm yelling: `Eighteen! Eighteen!' "

At that moment, he saw a burst of flame in what looked to him like the shape of a Christmas tree, and a tremendous wave of heat struck him in the face. He heard popping — the sound, he later realized, of drug or perfume bottles exploding — and turned to run out.

He did not know it at the time, but a fire raging in the cellar had caused a vast section of the building's first floor to collapse, taking 10 firefighters down with it and killing two others who had not fallen in. The flames he had seen were rising straight up from the cellar to the rest of the building.

Standing in the street, Mr. Fernandez watched in horror as curtains of fire began to engulf the block.

A rescue party made heroic efforts to reach the doomed men, according to a history published in 1993 by the Uniformed Firefighters Association. One firefighter, stumbling forward in the darkness, reached the edge of the collapsed area and fell in. One hand clutched the nozzle of the hose as he fell, and for a few moments, he hung swaying over the abyss, flames licking at his body, before other firefighters pulled him to safety.

By now, it had become a five-alarm fire, and hundreds of firefighters from all over the city were arriving, including many who were off duty. Ultimately, some 2,000 firefighters responded; at the time it was the largest gathering at a single working fire in American history.

At 1:30 a.m. the first two bodies were carried out. Thousands of people, including Mayor John V. Lindsay, watched from the street.

Exhausted, Mr. Fernandez took the subway back to his home in Queens. He recalls drinking a tall glass of Scotch and trying unsuccessfully to sleep. After an hour, he went back to the site.

Day was breaking, and as the fire gradually came under control, 10 more bodies were found in the smoking ruins of the drugstore.

Mr. Andrews, the young fire buff, had been uptown when the fire started, complaining to another fire crew that Engine 18 did not see enough action. He raced downtown after hearing the alarms and joined the crowds in the street. He had no inkling that the men he worshiped were already dead.

After the last body was carried out at 11 a.m., hundreds of weary, soot-blackened firefighters walked across the street into Madison Square Park. They were led by John T. O'Hagan, the chief of department, who had known all the dead men.

"This is the saddest day in the 100-year history of the Fire Department," Chief O'Hagan said as the firefighters gathered around him and removed their helmets. "They never had a chance. I know that we all died a little in there."

No civilians were killed in the fire, which investigators said appeared to have been triggered by electrical wires in the basement of an art dealership that had been loaded with wood and flammable paints.

In the years afterward, the Fire Department marked the anniversary with annual memorial services. On the fifth anniversary, Mayor Lindsay spoke, conjuring up still-fresh memories of the scene. On the 10th anniversary, Mayor Abraham D. Beame presided.

In 1986, Mr. O'Hagan, then a former fire commissioner, said he thought the department's annual memorial services for firefighters who die in the line of duty should be moved to Oct. 17.

"Oct. 17 should always be the first and most revered date on the New York City Fire Department calendar," he said.

Formerly embedded in the sidewalk, the simple plaque now affixed to the Madison Green building on 23rd Street was dedicated at the ceremony. But after an observance of the 25th anniversary, in 1991, the annual rites faded away. Nothing came of Commissioner O'Hagan's proposal.

As the 35th anniversary of the fire approached in 2001, Mr. Fernandez, who retired from the department in 1990, began urging officials to arrange a remembrance. On Sept. 7, Peter J. Ganci Jr., then the chief of department, promised him something would be done.

Four days later, Chief Ganci was dead, along with 342 other members of the department. Suddenly the '66 fire seemed almost meaningless by comparison, and Mr. Fernandez dropped his efforts for a year.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

REST IN PEACE TO THE 12......NEVER FORGET !.....................The FF mentioned in the story above who fell into the hole after the collapse while searching for his Unit & held onto the Nozzle & was pulled out was a FF i knew whose Father let me keep my car in their garage while i was in Viet Nam......His name was John "Jack" Donovan ......he lived for several years after this incident & after transferring to LAD*173 made a Roof Rope Rescue being lowered into Jamaica Bay off the North Channel Bridge to rescue a person in the water ...he later passed away from a stroke while a Member of LAD*173.....His Brother Tom was a FF in ENG*53....Manny Fernandez who was very active in FDNY Boxing still lives in Astoria....... Another friend of mine Ed Pospisil was a member of the Fire Patrol & had been in the cellar prior to the collapse & drew a map that was instrumental in ascertaining the correct location to breach a wall & locate the Members in the cellar & received the FDNY Albert S. Johnston Medal ....He subsequently became a career FF in Hartford Conn Retiring as a CPT.... ALSO let us NEVER FORGET the Bernard Tepper Triangle here in QNS named in Honor of FF Bernard Tepper ENG*18 that day...it is on the intersection of Homelawn St & the South Service Road of the Grand Central Parkway just where Utopia Parkway ends South of QNS College ...JK ..68jk09.

www.nytimes.com/2006/10/17/nyregion/17fire.html

www.nyfd.com/history/23rd_street/23rd_street.html

...................

BOX 598 10-17-66

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

October 12, 2003

A Grievous Day, Eclipsed by Sept. 11

By ROBERT F. WORTH

On Oct. 17, 1966, 12 firefighters died while responding to a catastrophic fire across Broadway from the Flatiron Building. For 35 years, the tragedy remained the New York Fire Department's single greatest loss of life.

For more than two decades, the city marked the anniversary with a solemn ceremony. But in the early 1990's, several years before Oct. 17 was eclipsed by Sept. 11 as the saddest date on the firefighters' calendar, memories began to dim, and the city stopped holding memorial services for those 12 dead men.

The terrorist attack is still an open wound. Flowers and candles can still be seen in front of firehouses that lost men, and ground zero remains a somber pilgrimage site. T-shirts proclaim that we will "never forget."

But we do forget. Like many before it, the '66 fire has begun fading into history. All that now remains at the site, a high-rise on East 23rd Street facing Madison Square Park, is a small bronze plaque with the date and the names of the dead.

Calamities cry out for attention every day, and the sad truth is that huge numbers of casualties trump small ones. So it is not surprising that the loss of 343 firefighters on Sept. 11, 2001, has dwarfed every other Fire Department tragedy.

A small group of firefighters and relatives still gather on the anniversary of the '66 fire. A few have vowed to bring it back to the city's consciousness. But they know that time and totals are against them.

"When I started hearing the numbers after Sept. 11, I said to myself, `Well, 12 is nothing now,' " said Manuel Fernandez, who lost all but one of six fellow firefighters in Engine 18 in the '66 fire. "But that shouldn't mean we forget these guys. Twelve men never came home. And it meant a lot to the city at the time."

Mr. Fernandez has been urging city officials to revive a formal commemoration. As of now, there are no plans to do so, said the Fire Department's chief spokesman, Francis X. Gribbon.

"Unfortunately," he said, "there have been so many tragic losses in recent history that it would be hard to honor them all separately."

Photographs from the '66 fire eerily foreshadow the images of Sept. 11. Thousands of haggard firefighters gathered at the scene as the dead were carried out of the blackened building. Thousands more lined Fifth Avenue during the funeral cortege four days later. The heroism of the dead men was proclaimed in headlines for weeks afterward.

"It really stopped New York City," said Daniel Andrews, who at the time followed Engine 18 as a teenage fire buff and now works in the Queens borough president's office. "You could hear a pin drop on Fifth Avenue during those funerals."

It all began on a cool evening at 9:30 p.m. Mr. Fernandez, a former professional boxer who had been with Engine 18 on West 10th Street for six years, was upstairs in the kitchen eating a late supper when he heard the first alarm.

When Engine 18 arrived at 23rd Street and Broadway, several crews were already on the scene. Smoke was rising from one of the buildings along Broadway, but no flames were visible, and the firefighters were confused about the source of the fire.

"I dropped them off on the 23rd Street side, and it was hazy in there, like a pool room," Mr. Fernandez said. As the "chauffeur," his duty was to man the motor pump on the engine.

While on the street, he heard a dull roar and knew instantly that something was wrong. He went into the drugstore building where five of his fellow firefighters had gone and began crawling in darkness. "You had about a foot of clear vision," he recalled. "I'm yelling: `Eighteen! Eighteen!' "

At that moment, he saw a burst of flame in what looked to him like the shape of a Christmas tree, and a tremendous wave of heat struck him in the face. He heard popping — the sound, he later realized, of drug or perfume bottles exploding — and turned to run out.

He did not know it at the time, but a fire raging in the cellar had caused a vast section of the building's first floor to collapse, taking 10 firefighters down with it and killing two others who had not fallen in. The flames he had seen were rising straight up from the cellar to the rest of the building.

Standing in the street, Mr. Fernandez watched in horror as curtains of fire began to engulf the block.

A rescue party made heroic efforts to reach the doomed men, according to a history published in 1993 by the Uniformed Firefighters Association. One firefighter, stumbling forward in the darkness, reached the edge of the collapsed area and fell in. One hand clutched the nozzle of the hose as he fell, and for a few moments, he hung swaying over the abyss, flames licking at his body, before other firefighters pulled him to safety.

By now, it had become a five-alarm fire, and hundreds of firefighters from all over the city were arriving, including many who were off duty. Ultimately, some 2,000 firefighters responded; at the time it was the largest gathering at a single working fire in American history.

At 1:30 a.m. the first two bodies were carried out. Thousands of people, including Mayor John V. Lindsay, watched from the street.

Exhausted, Mr. Fernandez took the subway back to his home in Queens. He recalls drinking a tall glass of Scotch and trying unsuccessfully to sleep. After an hour, he went back to the site.

Day was breaking, and as the fire gradually came under control, 10 more bodies were found in the smoking ruins of the drugstore.

Mr. Andrews, the young fire buff, had been uptown when the fire started, complaining to another fire crew that Engine 18 did not see enough action. He raced downtown after hearing the alarms and joined the crowds in the street. He had no inkling that the men he worshiped were already dead.

After the last body was carried out at 11 a.m., hundreds of weary, soot-blackened firefighters walked across the street into Madison Square Park. They were led by John T. O'Hagan, the chief of department, who had known all the dead men.

"This is the saddest day in the 100-year history of the Fire Department," Chief O'Hagan said as the firefighters gathered around him and removed their helmets. "They never had a chance. I know that we all died a little in there."

No civilians were killed in the fire, which investigators said appeared to have been triggered by electrical wires in the basement of an art dealership that had been loaded with wood and flammable paints.

In the years afterward, the Fire Department marked the anniversary with annual memorial services. On the fifth anniversary, Mayor Lindsay spoke, conjuring up still-fresh memories of the scene. On the 10th anniversary, Mayor Abraham D. Beame presided.

In 1986, Mr. O'Hagan, then a former fire commissioner, said he thought the department's annual memorial services for firefighters who die in the line of duty should be moved to Oct. 17.

"Oct. 17 should always be the first and most revered date on the New York City Fire Department calendar," he said.

Formerly embedded in the sidewalk, the simple plaque now affixed to the Madison Green building on 23rd Street was dedicated at the ceremony. But after an observance of the 25th anniversary, in 1991, the annual rites faded away. Nothing came of Commissioner O'Hagan's proposal.

As the 35th anniversary of the fire approached in 2001, Mr. Fernandez, who retired from the department in 1990, began urging officials to arrange a remembrance. On Sept. 7, Peter J. Ganci Jr., then the chief of department, promised him something would be done.

Four days later, Chief Ganci was dead, along with 342 other members of the department. Suddenly the '66 fire seemed almost meaningless by comparison, and Mr. Fernandez dropped his efforts for a year.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

REST IN PEACE TO THE 12......NEVER FORGET !.....................The FF mentioned in the story above who fell into the hole after the collapse while searching for his Unit & held onto the Nozzle & was pulled out was a FF i knew whose Father let me keep my car in their garage while i was in Viet Nam......His name was John "Jack" Donovan ......he lived for several years after this incident & after transferring to LAD*173 made a Roof Rope Rescue being lowered into Jamaica Bay off the North Channel Bridge to rescue a person in the water ...he later passed away from a stroke while a Member of LAD*173.....His Brother Tom was a FF in ENG*53....Manny Fernandez who was very active in FDNY Boxing still lives in Astoria....... Another friend of mine Ed Pospisil was a member of the Fire Patrol & had been in the cellar prior to the collapse & drew a map that was instrumental in ascertaining the correct location to breach a wall & locate the Members in the cellar & received the FDNY Albert S. Johnston Medal ....He subsequently became a career FF in Hartford Conn Retiring as a CPT.... ALSO let us NEVER FORGET the Bernard Tepper Triangle here in QNS named in Honor of FF Bernard Tepper ENG*18 that day...it is on the intersection of Homelawn St & the South Service Road of the Grand Central Parkway just where Utopia Parkway ends South of QNS College ...JK ..68jk09.

www.nytimes.com/2006/10/17/nyregion/17fire.html

www.nyfd.com/history/23rd_street/23rd_street.html

...................

- Joined

- May 6, 2010

- Messages

- 17,548

After the 23rd St Fire in 1966 Memorial Day was held at the site of the 23rd St Fire on Oct 17 each year for several years until 1970 when it was moved back to The Memorial at 100 St.....the first year it went back to 100 St. we were standing in ranks during the Ceremony & the Officials at the base of the Monument suddenly started whispering to each other & some left.....we figured something was going on . Sadly FF Edward J. Tuite of R*1 while cutting a roof at a commercial fell into a shaft & was killed during the Ceremony.

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2007

- Messages

- 1,620

Continued Rest in Peace to the 12 lost that terrible night.

- Joined

- Nov 2, 2020

- Messages

- 1,327

Rest In Peace gentlemen, you WILL NEVER BE FORGOTTEN!

- Joined

- May 6, 2010

- Messages

- 17,548

Remembering the deadly 1966 23rd Street Fire that killed 12 firefighters in NYC

On Oct. 17, 1966, 12 firefighters were killed in what was the deadliest day for the New York City Fire Department until the 9/11 terror attacks. Two chiefs, two lieutenants and eight firefighters l…

www.nydailynews.com

www.nydailynews.com