You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FDNY and NYC Firehouses and Fire Companies - 2nd Section

- Thread starter mack

- Start date

mack said:Squad 41, Engine 83/Ladder 29, Engine 304/Ladder 151:

http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/12-06_firehouses.pdf

305

NYC Landmark Preservation Commission - what does it mean for historic FDNY firehouses

"It means your building has special historical, cultural, or aesthetic value to the City of New York, state or nation, is an important part of the City's heritage and that LPC must approve in advance any alteration, reconstruction, demolition, or new construction affecting the designated building."

History:

"The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) is the largest municipal preservation agency in the nation. It is responsible for protecting New York City's architecturally, historically, and culturally significant buildings and sites by granting them landmark or historic district status, and regulating them after designation.

The agency is comprised of a panel of 11 commissioners who are appointed by the Mayor and supported by a staff of approximately 80 preservationists, researchers, architects, historians, attorneys, archaeologists, and administrative employees.

There are more than 36,000 landmark properties in New York City, most of which are located in 141 historic districts and historic district extensions in all five boroughs. The total number of protected sites also includes 1,405 individual landmarks, 120 interior landmarks, and 10 scenic landmarks."

https://www1.nyc.gov/site/lpc/about/about-lpc.page

"It means your building has special historical, cultural, or aesthetic value to the City of New York, state or nation, is an important part of the City's heritage and that LPC must approve in advance any alteration, reconstruction, demolition, or new construction affecting the designated building."

History:

"The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) is the largest municipal preservation agency in the nation. It is responsible for protecting New York City's architecturally, historically, and culturally significant buildings and sites by granting them landmark or historic district status, and regulating them after designation.

The agency is comprised of a panel of 11 commissioners who are appointed by the Mayor and supported by a staff of approximately 80 preservationists, researchers, architects, historians, attorneys, archaeologists, and administrative employees.

There are more than 36,000 landmark properties in New York City, most of which are located in 141 historic districts and historic district extensions in all five boroughs. The total number of protected sites also includes 1,405 individual landmarks, 120 interior landmarks, and 10 scenic landmarks."

https://www1.nyc.gov/site/lpc/about/about-lpc.page

Squad 288/Hazmat 1 firehouse efforts for Landmark status:

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/10/nyregion/seeking-landmark-status-for-a-nondescript-firehouse-that-lost-many-on-sept-11.html

http://www.queensledger.com/view/full_story/23578469/article-Landmark-proposal-for-century-old-firehouse-in-Maspeth?instance=lead_story_left_column

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/10/nyregion/seeking-landmark-status-for-a-nondescript-firehouse-that-lost-many-on-sept-11.html

http://www.queensledger.com/view/full_story/23578469/article-Landmark-proposal-for-century-old-firehouse-in-Maspeth?instance=lead_story_left_column

Ladder 14 firehouse 120 E 125th Street Harlem 11th/12th Bn, 4th/5th Division "Super Tower"

Suburban Ladder 14 organized 120 E 125th Street former volunteer firehouse 1865

Suburban Ladder 14 became Ladder 14 1868

Ladder 14 moved to 209 E 122nd Street 1888

Ladder 14 moved to new firehouse 120 E 125th Street 1889

Ladder 14 moved to 2282 3rd Avenue at Engine 35 1975

Notes:

Engine 36 located at 120 E 125th Street 1975-2003

Battalion 12 located at 120 E 120th Street 1904-1974 and 1990-1995

Battalion 12-2 located at 120 E 120th Street 1968-1969

Pre-FDNY:

Volunteer Mechanics Ladder 7 new firehouse 120 E 120th Street 1861-1865

120 E 120th Street firehouse 1861-1888 (Suburban Ladder 14):

120 E 120th Street firehouse built 1188-1189:

2282 3rd Avenue current firehouse w/Engine 35/Battalion 12:

Ladder 14:

Ladder 14:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lPnuxHdvldo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOk4ZvJdSmg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHOj6cHnUDA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7Mq2KnkJ4s

Ladder 14 Medals:

JOHN HUGHES FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 25, 1898 1900 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

JOHN FREDENBERG FF. LAD. 14 MAY 21, 1899 1900 TREVOR-WARREN

ANDREW F. FITZGERALD FF. LAD. 14 MAR. 17, 1899 1900 HUGH BONNER

WILLIAM CLARK FF. LAD. 14 MAR. 17, 1899 1900 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

Later - Deputy Chief 4th Division - Career: Appointed 1895 and served in Ladder 10 then on Fulton Street. Made Lieutenant in 1900, Captain the same year, Battalion Chief in 1910, Deputy Chief in 1925. Prior to this he served five years in the US Navy.

Hotel Windsor Fire: As a Fireman, performed daring rescue at the Hotel Windsor fire on March 17, 1899 which killed 45 victims. The hotel located at Fifth Avenue and Forty-Sixth Street just as the St. Patrick's Day parade was passing. Forty-five guests perished and hundreds of others were severely burned.

FF Clark working with another firemen made a half dozen rescues with the aid of scaling ladders. They were being urged to rest after the first rescues when a woman and her maid, Mrs. Joseph Howard, Jr and Mrs. Grace Harrison, stranded on the 5th floor and about to jump, called for help. As he was rescuing these two, another woman screamed from an adjoining room and threatened to jump. He worked his way from one sill to another and assisted this woman across, after which the three persons were rescued. For these feats he received the Gordon Bennett medal.

Chief Clark was cited for bravery a total of seven times during his career. In addition to the 1899 Bennett Medal, he was cited in 1900 when saved his company of men by evacuating them from the Tarrant Drug Store just before it exploded and collapsed; in 1904 for preventing a psychiatric patient from jumping from a window at the Manhattan Eye and Ear Infirmary; and for rescuing a number of horses from a stable fire in 1908.

CHARLES M. LOUTH FF. LAD. 14 MAY 23, 1905 1906 TREVOR-WARREN

PATRICK R. O'CONNOR FF. LAD. 14 FEB. 20, 1917 1918 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

GEORGE J. NELSON FF. LAD. 14 FEB. 20, 1917 1918 TREVOR-WARREN

FERDINAND Z. RIVIELLO FF. LAD. 14 MAY 24, 1926 1927 VAN HEUKELON

LODD - February 20, 1933

JOHN H. SIEBEL FF. LAD. 14 APR. 22, 1935 1936 SCOTT

JOHN HALPIN FF. LAD. 14 APR. 22, 1935 1936 CRIMMINS

RICHARD H. RICHARDSON FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 24, 1952 1953 LA GUARDIA

WILLIAM A. GERRIE PROBIE LAD. 14 JAN. 15, 1956 1957 MC ELLIGOTT

WALLACE R. STORCH FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 15, 1956 1957 LA GUARDIA

KARL F. F. ERB FF. LAD. 14 JUN. 29, 1956 1957 O'DWYER

SALVATORE CARDILLO FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 17, 1958 1959 COMMERCE

WALLACE R. STORCH FF. LAD. 14 JUL. 20, 1958 1959 LA GUARDIA

JOSEPH G. PERAGINE FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 24, 1960 1961 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

FF Joseph G. Peragine, Ladder Company 14, received the James Gordon Bennett medal, traditionally the department?s top medal for valor, for rescuing a woman and a child from a fire in the Harlem area on December 24, 1960. and brother-inlaw Lester Gannon. He served in the United States Marines as a radio operator with the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines Regiment in 2nd Marine Division. Joseph was a New York Fireman, Ladder 14, for 20 years and was a member of The Uniformed Fire Officers Association 25 Group System.

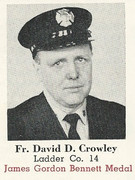

DAVID D. CROWLEY FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 17, 1963 1964 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

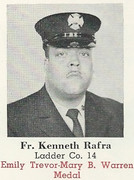

KENNETH RAFRA FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 17, 1963 1964 TREVOR-WARREN

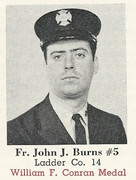

JOHN J. BURNS FF. LAD. 14 NOV. 16, 1963 1964 CONRAN

WILLIAM T. TRACY FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 17, 1964 1965 KANE

AUBREY L. NELSON FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 1, 1964 1965 CRIMMINS

DAVID D. CROWLEY FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 17, 1963 1966 HARRY M. ARCHER

WILLIAM D. RICE FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 31, 1972 1973 DELEHANTY

THOMAS P. COLLINS FF. LAD. 14 APR. 14, 1977 1978 HISPANIC

WALTER R. MANTHEY FF. LAD. 14 MAY 31, 1977 1978 GOLDENKRANZ

JAMES M. KIERNAN FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 31, 1979 1980 SCOTT

THOMAS K. MARTIN CAPT. LAD. 14 L-34 DEC. 19, 1982 1983 LAUFER

STEPHEN P. SZAMBEL FF. LAD. 14 APR. 16, 1985 1986 CINELLI

RICHARD VOLPE FF. LAD. 14 JUL. 31, 1985 1986 THOMPSON

WILLIAM E. BRUSE FF. LAD. 14 L-30 DEC. 20, 1986 1987 LAUFER

THOMAS M. MONTGOMERY FF. LAD. 14 MAY 4, 1989 1990 COMPANY OFFICERS

WILLIAM E. BRUSE FF. LAD. 14 APR. 14, 1993 1994 WILLIAMS

ALL MEMBERS LAD. 14 JUN. 30, 1994 1995 ELSASSER

BRIAN A. NEVILLE FF. LAD. 14 SEP. 1, 1995 1996 POLICE HONOR

Ladder LODDs:

FIREFIGHTER PATRICK CONLIN LADDER 14 JUNE 9, 1895

Fireman Patrick Conlin of Ladder 14 was returning from his meal break when he saw Ladder 14 responding to a fire at 165 East 112th Street. Ladder 14 was responding from their quarters at 120 East 125th Street and was heading down Lexington Avenue to East 115th Street. He tried to jump on the running board of the speeding apparatus but missed and was run over. The truck's rear wheels passed over his body fracturing his thighbone and caused severe injuries to the abdomen. He was taken to Harlem Hospital where he died in the early evening. Conlin was thirty-seven years old and had been in the Department for twelve years. He spent four years with Ladder 14. He was married, but had no children. The fire at 165 East 112th Street was in the cellar in a pile of excelsior and was put out with a pail of water. (From "The Last Alarm")

FIREFIGHTER MATTHEW J. DUNN LADDER 14 October 14, 1931

Fireman Matthew Dunn, twenty-seven years old, of Ladder 14, died in the Hospital for Joint Diseases from the effects of burns. The day before while fighting a fire at 106 West 123rd Street he was burned by a still that exploded in a garage. He was married and lived with his wife and two children at 2886 Briggs Avenue in the Bronx. (from "The Last Alarm")

FIREFIGHTER FERDINAND RIVIELLO LADDER 14 February 20, 1933

Fireman Ferdinand Z. Riviello, driver of Hook & Ladder Company 14, collided with a taxicab at East 125th Street and Lenox Avenue while responding to an alarm. Riviello and four other members of Ladder 14 were thrown to the ground. Riviello died almost instantly while the other four received minor injuries. The apparatus continued along Lenox Avenue with nobody driving the front end. The tiller man tried to control the back end but the rig slammed into a lunchroom. The taxi cab driver was intoxicated and was arrested for homicide. (from "The Last Alarm")

FIREFIGHTER LAWRENCE PERCHUCK LADDER 14 November 27, 1967

Firefighter Perchuck, a 30 year veteran assigned to Ladder 14, died as a result of injuries sustained in the performance of his duties.

FIREFIGHTER GEORGE L. COLLINS BATTALION 12 November 15, 1968

Firefighter Collins died November 15, 1968 as a result of injuries sustained operating at Manhattan Box 1479 on July 8, 1968. Firefighter Collins suffered an acute heart attack. He was originally assigned to Engine 35 and was a Battalion 12 aide for 8 years.

RIP. Never forget.

Pre-FDNY volunteer history:

H&L No. 7. - "Mechanics" - Was organized September 7, 1837; located at One Hundred and Twenty-sixth Street and Third Avenue; removed in 1861 to One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street and Third Avenue, and remained there until the camp fires of the Old Department were extinguished. About the time of the organization of No. 7, there was a "road house" at the northwest corner of One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street and Third Avenue, known as "Bradshaw's," a favorite stopping place for fast trotters. Bradshaw was one of the early foreman of No. 7. John Kenyon, postmaster of Harlem for sixteen years, was foreman for a long time, also John Prophet, Samuel Christie, and Henry A. Southerton. Many of the best citizens of Harlem were members. Colwell, the lumber merchant; George W. Thompson, an old settler and businessman, and Frederick Goll, who was the last foreman. When the Metropolitan Department took control, No. 7 was invited to remain; they accepted, and each received at the rate of one thousand dollars per year; served with the New Department about fourteen months, and then passed away. Afterwards the remaining members claimed full pay, and put their claims in the hands of "Tom Fields." He collected the money, and, it is alleged, reimbursed himself the like generous soul he was. ("Our Firemen, The History of the NY Fire Departments")

Surburban Companies:

When the paid department was established in 1865, several new areas that had become part of NYC were not yet developed, had poor roads and sparse populations. Much was famlands. Suburban engine and ladder companies were established to replace volunteer fire companies. These suburban companies were FDNY units and performed the basic firefighting functions of FDNY companies. FDNY members appoinited to these units did not work the rigorous hours that members worked in regular companies who only had 3 hours off per day to go home for meals. Suburban members retained their previous jobs, responded to alarms during the day and lived at their firehouses at night. Most were former volunteer members. Apparatus was hand-drawn and light-duty. Suburban companies were transitioned to regular FDNY units by 1868.

Old FDNY sleeve awards: known as "bugs" by FDNY members

120 E 125th Street firehouse - National Register Historic Places - 2013:

https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/13000309.htm

Firehouse was designed by Napoleon LeBrun, official architect of the New York City Fire Department. When son Pierre joined him the firm became N. LeBrun & Son. LeBrun produced 42 structures for the fire department.

120 E 125th Street - former firehouse:

https://ny.curbed.com/2014/8/30/10054016/east-harlem-firehouse-to-become-new-cultural-center

https://ny.curbed.com/2014/9/12/10047934/glimpse-east-harlems-firehouse-turned-cultural-center

https://www.nycedc.com/project/caribbean-cultural-center-african-diaspora-institute

Suburban Ladder 14 organized 120 E 125th Street former volunteer firehouse 1865

Suburban Ladder 14 became Ladder 14 1868

Ladder 14 moved to 209 E 122nd Street 1888

Ladder 14 moved to new firehouse 120 E 125th Street 1889

Ladder 14 moved to 2282 3rd Avenue at Engine 35 1975

Notes:

Engine 36 located at 120 E 125th Street 1975-2003

Battalion 12 located at 120 E 120th Street 1904-1974 and 1990-1995

Battalion 12-2 located at 120 E 120th Street 1968-1969

Pre-FDNY:

Volunteer Mechanics Ladder 7 new firehouse 120 E 120th Street 1861-1865

120 E 120th Street firehouse 1861-1888 (Suburban Ladder 14):

120 E 120th Street firehouse built 1188-1189:

2282 3rd Avenue current firehouse w/Engine 35/Battalion 12:

Ladder 14:

Ladder 14:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lPnuxHdvldo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOk4ZvJdSmg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHOj6cHnUDA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7Mq2KnkJ4s

Ladder 14 Medals:

JOHN HUGHES FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 25, 1898 1900 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

JOHN FREDENBERG FF. LAD. 14 MAY 21, 1899 1900 TREVOR-WARREN

ANDREW F. FITZGERALD FF. LAD. 14 MAR. 17, 1899 1900 HUGH BONNER

WILLIAM CLARK FF. LAD. 14 MAR. 17, 1899 1900 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

Later - Deputy Chief 4th Division - Career: Appointed 1895 and served in Ladder 10 then on Fulton Street. Made Lieutenant in 1900, Captain the same year, Battalion Chief in 1910, Deputy Chief in 1925. Prior to this he served five years in the US Navy.

Hotel Windsor Fire: As a Fireman, performed daring rescue at the Hotel Windsor fire on March 17, 1899 which killed 45 victims. The hotel located at Fifth Avenue and Forty-Sixth Street just as the St. Patrick's Day parade was passing. Forty-five guests perished and hundreds of others were severely burned.

FF Clark working with another firemen made a half dozen rescues with the aid of scaling ladders. They were being urged to rest after the first rescues when a woman and her maid, Mrs. Joseph Howard, Jr and Mrs. Grace Harrison, stranded on the 5th floor and about to jump, called for help. As he was rescuing these two, another woman screamed from an adjoining room and threatened to jump. He worked his way from one sill to another and assisted this woman across, after which the three persons were rescued. For these feats he received the Gordon Bennett medal.

Chief Clark was cited for bravery a total of seven times during his career. In addition to the 1899 Bennett Medal, he was cited in 1900 when saved his company of men by evacuating them from the Tarrant Drug Store just before it exploded and collapsed; in 1904 for preventing a psychiatric patient from jumping from a window at the Manhattan Eye and Ear Infirmary; and for rescuing a number of horses from a stable fire in 1908.

CHARLES M. LOUTH FF. LAD. 14 MAY 23, 1905 1906 TREVOR-WARREN

PATRICK R. O'CONNOR FF. LAD. 14 FEB. 20, 1917 1918 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

GEORGE J. NELSON FF. LAD. 14 FEB. 20, 1917 1918 TREVOR-WARREN

FERDINAND Z. RIVIELLO FF. LAD. 14 MAY 24, 1926 1927 VAN HEUKELON

LODD - February 20, 1933

JOHN H. SIEBEL FF. LAD. 14 APR. 22, 1935 1936 SCOTT

JOHN HALPIN FF. LAD. 14 APR. 22, 1935 1936 CRIMMINS

RICHARD H. RICHARDSON FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 24, 1952 1953 LA GUARDIA

WILLIAM A. GERRIE PROBIE LAD. 14 JAN. 15, 1956 1957 MC ELLIGOTT

WALLACE R. STORCH FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 15, 1956 1957 LA GUARDIA

KARL F. F. ERB FF. LAD. 14 JUN. 29, 1956 1957 O'DWYER

SALVATORE CARDILLO FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 17, 1958 1959 COMMERCE

WALLACE R. STORCH FF. LAD. 14 JUL. 20, 1958 1959 LA GUARDIA

JOSEPH G. PERAGINE FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 24, 1960 1961 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

FF Joseph G. Peragine, Ladder Company 14, received the James Gordon Bennett medal, traditionally the department?s top medal for valor, for rescuing a woman and a child from a fire in the Harlem area on December 24, 1960. and brother-inlaw Lester Gannon. He served in the United States Marines as a radio operator with the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines Regiment in 2nd Marine Division. Joseph was a New York Fireman, Ladder 14, for 20 years and was a member of The Uniformed Fire Officers Association 25 Group System.

DAVID D. CROWLEY FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 17, 1963 1964 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

KENNETH RAFRA FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 17, 1963 1964 TREVOR-WARREN

JOHN J. BURNS FF. LAD. 14 NOV. 16, 1963 1964 CONRAN

WILLIAM T. TRACY FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 17, 1964 1965 KANE

AUBREY L. NELSON FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 1, 1964 1965 CRIMMINS

DAVID D. CROWLEY FF. LAD. 14 JAN. 17, 1963 1966 HARRY M. ARCHER

WILLIAM D. RICE FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 31, 1972 1973 DELEHANTY

THOMAS P. COLLINS FF. LAD. 14 APR. 14, 1977 1978 HISPANIC

WALTER R. MANTHEY FF. LAD. 14 MAY 31, 1977 1978 GOLDENKRANZ

JAMES M. KIERNAN FF. LAD. 14 DEC. 31, 1979 1980 SCOTT

THOMAS K. MARTIN CAPT. LAD. 14 L-34 DEC. 19, 1982 1983 LAUFER

STEPHEN P. SZAMBEL FF. LAD. 14 APR. 16, 1985 1986 CINELLI

RICHARD VOLPE FF. LAD. 14 JUL. 31, 1985 1986 THOMPSON

WILLIAM E. BRUSE FF. LAD. 14 L-30 DEC. 20, 1986 1987 LAUFER

THOMAS M. MONTGOMERY FF. LAD. 14 MAY 4, 1989 1990 COMPANY OFFICERS

WILLIAM E. BRUSE FF. LAD. 14 APR. 14, 1993 1994 WILLIAMS

ALL MEMBERS LAD. 14 JUN. 30, 1994 1995 ELSASSER

BRIAN A. NEVILLE FF. LAD. 14 SEP. 1, 1995 1996 POLICE HONOR

Ladder LODDs:

FIREFIGHTER PATRICK CONLIN LADDER 14 JUNE 9, 1895

Fireman Patrick Conlin of Ladder 14 was returning from his meal break when he saw Ladder 14 responding to a fire at 165 East 112th Street. Ladder 14 was responding from their quarters at 120 East 125th Street and was heading down Lexington Avenue to East 115th Street. He tried to jump on the running board of the speeding apparatus but missed and was run over. The truck's rear wheels passed over his body fracturing his thighbone and caused severe injuries to the abdomen. He was taken to Harlem Hospital where he died in the early evening. Conlin was thirty-seven years old and had been in the Department for twelve years. He spent four years with Ladder 14. He was married, but had no children. The fire at 165 East 112th Street was in the cellar in a pile of excelsior and was put out with a pail of water. (From "The Last Alarm")

FIREFIGHTER MATTHEW J. DUNN LADDER 14 October 14, 1931

Fireman Matthew Dunn, twenty-seven years old, of Ladder 14, died in the Hospital for Joint Diseases from the effects of burns. The day before while fighting a fire at 106 West 123rd Street he was burned by a still that exploded in a garage. He was married and lived with his wife and two children at 2886 Briggs Avenue in the Bronx. (from "The Last Alarm")

FIREFIGHTER FERDINAND RIVIELLO LADDER 14 February 20, 1933

Fireman Ferdinand Z. Riviello, driver of Hook & Ladder Company 14, collided with a taxicab at East 125th Street and Lenox Avenue while responding to an alarm. Riviello and four other members of Ladder 14 were thrown to the ground. Riviello died almost instantly while the other four received minor injuries. The apparatus continued along Lenox Avenue with nobody driving the front end. The tiller man tried to control the back end but the rig slammed into a lunchroom. The taxi cab driver was intoxicated and was arrested for homicide. (from "The Last Alarm")

FIREFIGHTER LAWRENCE PERCHUCK LADDER 14 November 27, 1967

Firefighter Perchuck, a 30 year veteran assigned to Ladder 14, died as a result of injuries sustained in the performance of his duties.

FIREFIGHTER GEORGE L. COLLINS BATTALION 12 November 15, 1968

Firefighter Collins died November 15, 1968 as a result of injuries sustained operating at Manhattan Box 1479 on July 8, 1968. Firefighter Collins suffered an acute heart attack. He was originally assigned to Engine 35 and was a Battalion 12 aide for 8 years.

RIP. Never forget.

Pre-FDNY volunteer history:

H&L No. 7. - "Mechanics" - Was organized September 7, 1837; located at One Hundred and Twenty-sixth Street and Third Avenue; removed in 1861 to One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street and Third Avenue, and remained there until the camp fires of the Old Department were extinguished. About the time of the organization of No. 7, there was a "road house" at the northwest corner of One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street and Third Avenue, known as "Bradshaw's," a favorite stopping place for fast trotters. Bradshaw was one of the early foreman of No. 7. John Kenyon, postmaster of Harlem for sixteen years, was foreman for a long time, also John Prophet, Samuel Christie, and Henry A. Southerton. Many of the best citizens of Harlem were members. Colwell, the lumber merchant; George W. Thompson, an old settler and businessman, and Frederick Goll, who was the last foreman. When the Metropolitan Department took control, No. 7 was invited to remain; they accepted, and each received at the rate of one thousand dollars per year; served with the New Department about fourteen months, and then passed away. Afterwards the remaining members claimed full pay, and put their claims in the hands of "Tom Fields." He collected the money, and, it is alleged, reimbursed himself the like generous soul he was. ("Our Firemen, The History of the NY Fire Departments")

Surburban Companies:

When the paid department was established in 1865, several new areas that had become part of NYC were not yet developed, had poor roads and sparse populations. Much was famlands. Suburban engine and ladder companies were established to replace volunteer fire companies. These suburban companies were FDNY units and performed the basic firefighting functions of FDNY companies. FDNY members appoinited to these units did not work the rigorous hours that members worked in regular companies who only had 3 hours off per day to go home for meals. Suburban members retained their previous jobs, responded to alarms during the day and lived at their firehouses at night. Most were former volunteer members. Apparatus was hand-drawn and light-duty. Suburban companies were transitioned to regular FDNY units by 1868.

Old FDNY sleeve awards: known as "bugs" by FDNY members

120 E 125th Street firehouse - National Register Historic Places - 2013:

https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/13000309.htm

Firehouse was designed by Napoleon LeBrun, official architect of the New York City Fire Department. When son Pierre joined him the firm became N. LeBrun & Son. LeBrun produced 42 structures for the fire department.

120 E 125th Street - former firehouse:

https://ny.curbed.com/2014/8/30/10054016/east-harlem-firehouse-to-become-new-cultural-center

https://ny.curbed.com/2014/9/12/10047934/glimpse-east-harlems-firehouse-turned-cultural-center

https://www.nycedc.com/project/caribbean-cultural-center-african-diaspora-institute

120 E 125th Street Firehouse - Landmark Status Report 1997

Fire Hook & Ladder Company No. 14

Harlem, Manhattan

Summary

Fire Hook & Ladder Company No. 14, built in 1888-89, was designed by the architectural firm of N. LeBrun & Sons in the Romanesque Revival style. Between the years of 1880 and 1895, N. LeBrun & Sons helped to define the Fire Department's expression of civic architecture, both functionally and symbolically, in more than 40 buildings. Hook & Ladder No. 14 is characteristic of N. LeBrun & Sons' numerous mid-block firehouses, reflecting the firm's attention to materials, stylistic detail, plan, and setting. Built on the site of an earlier volunteer fire company, and then a professional suburban company, this firehouse also represents nearly 150 years of the New York Fire Department's history. Since 1975, it has been the home of Fire Engine Co. No. 36.

The Fire Department of the City of New York

The origins of New York's Fire Department date to the city's beginning as the Dutch colony New Amsterdam. Leather fire buckets, first imported from Holland and later manufactured by a cobbler in the colony, were required in every household. Regular chimney inspections and the "rattle watch" patrol helped protect the colony during the Dutch period. By 1731, under English rule, two "engines" were imported from London and housed in wooden sheds in lower Manhattan.

The Common Council authorized a volunteer force in 1737, and the Volunteer Fire Department of the City of New York was officially established by an act of the state legislature in 1798. As the city grew, this force was augmented by new volunteer companies. Between 1800 and 1850, seven major fires occurred, leading to the establishment of a building code and the formation of new volunteer fire companies on a regular basis. The number of firemen grew from 600 in 1800 to more than 4,000 by 1865.

Intense rivalries among the companies developed, stemming in large part from the Volunteer Fire Department's role as a significant political influence in municipal affairs. The Tammany political machine was especially adept at incorporating the fire department into its ranks. Since the 1820s it was common knowledge that "a success in the fire company was the open sesame to success in politics."

During the peak years of Tammany's power, increasingly intense competition among companies began to hinder firefighting, creating public exasperation with the volunteer force. Brawls among firemen at the scene of fires and acts of sabotage among the companies became commonplace. In the 1860s, an alliance between the Republican controlled state legislature (which wanted to impair Tammany Hall's political control) and fire insurance companies (who wanted more efficient firefighting) played on this public sentiment to replace the volunteers with a paid force.

On March 30, 1865, the New York State Legislature established the Metropolitan Fire District, comprising New York and Brooklyn. This act abolished New York's Volunteer Fire Department and created the Metropolitan Fire Department, a paid professional force under the jurisdiction of the state. By the end of the year, the city's 124 volunteer companies with more than 4,000 men had retired or disbanded to be replaced by thirty-three engine companies and twelve ladder companies operated by a force of some 500 men.

With the creation of a professional Fire Department in 1865, improvements were immediate. Regular service was extended to 106th Street in Manhattan, with suburban companies further north, and its telegraph system was upgraded. Early in 1865 there were only 64 call boxes in New York, none of them located above 14th Street. Within the next year and a half, the number had increased to 187.3 Horse-drawn, steam-powered apparatus were required for all companies.

The firehouse crews were standardized at twelve men (as opposed to a total of up to 100 men per firehouse under the volunteer system), and the Department took on a serious, disciplined character.

In 1869, "Boss" William Marcy Tweed's candidate for New York State governor was elected, and he quickly regained control of the Fire Department through the Charter of 1870 (commonly known as the "Tweed Charter"). Only three years later, this charter was revoked when Tweed was sentenced to prison for embezzling millions from the city. Permanently under city control after 1870, the Fire Department (separated into a New York Department and a Brooklyn Department) retained its professional status and proceeded to modernize rapidly. While no new buildings were built until 1879-80 (the last one built prior to this was the Fireman's Hall in 18546), the companies continually invested in modern apparatus and new technologies.

Firehouse Function and Planning in the LeBrun Era

With the creation of the Metropolitan Fire Department in 1865 ? and the supposed removal of Tammany control of the companies ? the Common Council hoped to filter out remaining Tammany influence by banning any firehouse construction for five years.

The ban, for reasons unknown, lasted until 1879, when, under Fire Chief Eli Bates, the department embarked on a major campaign for new firehouse construction throughout the city, but especially in northern sections.

N. LeBrun & Sons designed all of the Fire Department's forty-two structures built between 1880 and 1895. It is not clear exactly why the LeBrun firm was commissioned by the Fire Department to serve as its sole architect during these years. Napoleon LeBrun had a personal interest in promoting the use of professional architects rather than contractors for municipal building projects. In 1879, LeBrun was the representative of the American Institute of Architects on the Board of Examiners of the Building Bureau of the Fire Department, a position he held for eighteen years.

This position may well have led to the commission by the Fire Department, which ultimately did set a standard for firehouse design in New York.

With the professionalization of the firefighting force in 1865, the spatial requirements of the firehouse were established.8 The ground floor functioned primarily as storage for the apparatus, and the second and third floors housed the dormitory, kitchen, and captain's office. While the basic function of the house had not changed by 1880 (and is essentially the same today), LeBrun is credited with standardizing the main program components, while introducing some minor, but important, innovations in the plan.

For example, when horses were first introduced into the system, they were stabled outside behind the firehouse. Valuable time was lost in bringing them inside to the apparatus. LeBrun's firehouses included horse stalls inside the building, at the rear of the apparatus floor, and some houses had special features related to the horses' care and feeding.

The LeBrun firehouses also neatly accommodated the necessity of drying the cotton hoses after each use, incorporating an interior hose-drying "tower" which ran the height of the building along one wall, thus economizing valuable space in the firehouse.

History of Hook & Ladder Company No. 14

Because northern Manhattan was sparsely populated in 1865, the Metropolitan Fire Department established suburban companies to serve that area. These companies, both engine and ladder, functioned slightly differently than their counterparts downtown. The suburban firefighters had a lighter work schedule and received less pay, and the companies were assigned hand-drawn apparatus instead of the horse-drawn steamers and trucks assigned to the regular companies. In October 1865, Suburban Ladder No. 14 was established at 120 East 125th Street, inheriting the property and equipment of the volunteer Mechanics No. 7." The city grew rapidly northward, and less than three years later, on January 1, 1868, the Fire Department closed all suburban companies.

Hook & Ladder No. 14 replaced Suburban Ladder No. 14. It continued to operate out of the old volunteer firehouse at 120

East 125th Street until 1888, when a new building was constructed in response to Harlem's growing population.

As reported in the Fire Department's Annual Report of 1889, the department recognized the need to prepare for the encroaching development of the city northward in Manhattan:

There is also imperative need of a number of additional companies north of One Hundred and Tenth Street, where no increase in the fire-extinguishing force has been made since the organization of the Department, to keep pace with the large growth in population and buildings.

The new structure for Hook & Ladder No. 14, designed by the architectural firm of N. LeBrun & Sons, was erected in 1888-89.13 In the first year in its new home, the company was staffed by twelve firemen and three horses for its hook and ladder truck; it responded to 146 alarms and fought 93 fires.

The structure was home to Hook & Ladder Company No. 14 until 1975. No. 14 relocated to 2282 Third Avenue, and Engine Company No. 36 relocated here from 1849 Park Avenue.

Built in the middle of the fifteen-year period in which the LeBrun firm designed for the Fire Department, Hook & Ladder No. 14 is representative of the firm's approach to firehouse design during a highly politicized period for the Fire Department and a time of intense urbanization for the city at large. The LeBrun era facade designs reflected the firehouses' surroundings in scale, materials, adherence to the street wall, and stylistically as well. Because the firehouse was home to the firemen, these designs project a certain domesticity within their functional character; this is particularly true for Hook & Ladder No. 14, as expressed in the mansard roof and attic gable.

While Hook & Ladder No. 14 reflects its context in scale and composition, but is also distinguished as both a civic and a utilitarian structure. East 125th Street is comprised mainly of commercial buildings built near the end of the nineteenth century.

The Queen Anne-Romanesque Revival Mount Morris Bank (Lamb & Rich, 1883-85, 1889-90, designated New York City Landmark) at East 125th Street and Park Avenue is the grandest of these, although it is now in a state of serious neglect. The surrounding residential neighborhood includes numerous rowhouses from the same period, reflecting Harlem's early development as an affluent community. The Hook & Ladder No. 14 is a significant reminder of that period, and along with the Mt. Morris Watch Tower (1855, designated New York City Landmark) and the Harlem Courthouse (Thom & Wilson, 1891-93, designated New York City Landmark), is an important symbol of the city's municipal development in the nineteenth century.

N. LeBrun & Sons, Architects

Napoleon Eugene Charles LeBrun (1821-1901) was born to French immigrant parents in Philadelphia. At fifteen years of age he was placed in the office of classicist Thomas Ustick Walter (1804-1887), where he remained for six years.

LeBrun began his own practice in 1841 in Philadelphia where he had several major commissions ? including the Cathedral of SS. Peter and Paul (1846-64) and the Academy of Music (1852-57) - before moving to New York in 1864. His Second Empire Masonic Temple competition submission of 1870 did much to establish his reputation in New York. In the same year his son Pierre joined him and the firm became Napoleon LeBrun & Son in 1880. In 1892 the firm became Napoleon LeBrun & Sons in recognition of his youngest son, Michel. All three were active members of the American Institute of Architects.

Napoleon LeBrun was first commissioned by the Fire Department of the City of New York in 1880. Until 1895, N. LeBrun & Sons designed more than 40 buildings for the Fire Department throughout Manhattan, including many firehouses, a warehouse, and a fire pier.

The firm's fifteen-year building campaign resulted in an average of two to three firehouses each year. In some cases, nearly identical buildings were erected; Hook & Ladder No. 14 has a twin in Engine Company No. 56 at 120 West 83rd Street (1888-89, located in the Upper West Side/Central Park West Historic District).

Most of the designs used classical detailing and overall symmetry (in part dictated by the large vehicular entrance on a narrow lot), but provided a wide range of aesthetic expression.

The firm created two large, elaborate buildings for the Fire Department during this period: the Fire Department Headquarters at 157-159 East 67th Street (now Engine Company No. 39/Ladder Company No. 16, 1884-86) and Engine Company No. 31, 87 Lafayette Street (1895, a designated New York City Landmark). The Headquarters building is a strong expression of the Romanesque Revival style, and in the years following its completion, several smaller houses were designed in a subdued version of the style. Hook & Ladder No. 14 is one example.

Engine Company No. 31, the firm's best known firehouse design, is the least representative of its tenure with the Fire Department and marks a transition between the restrained, classical elegance of the majority of its firehouses and the increasingly monumental designs of other architects which followed at the turn of the century.

Engine Company No. 31 is a freestanding structure for a triple engine company modeled on sixteenth-century Loire Valley chateaux. It was a distinct departure from the firm's usual "storefront" design and is considered the firm's most impressive civic design. Also of note was the firm's acclaimed Hook & Ladder Company No. 15 at Old Slip (1885, demolished), which was designed in the style reminiscent of a seventeenth-century Dutch house.

While they are best known in New York City for the firehouses, the LeBruns designed several churches including the Church of the Epiphany (1870, demolished), Saint John-the-Baptist (1872), 211 West 30th Street, and St. Mary-the-Virgin (1894-95, a designated New York City Landmark), 133-145 West 46th Street. At the turn of the century, N. LeBrun & Sons achieved renown for office building design in Manhattan, most notably the home office of the Metropolitan Life Building at 1 Madison Avenue (1890-92, and annex tower, 1909, designated New York City Landmark) and the Home Life Insurance Company Building, 256-257 Broadway (1892-94, a designated New York City Landmark).

Building Description

Hook & Ladder Company No. 14 is a four-story brick and stone structure. Through its composition, colors, and subtle texture, the building expresses the Romanesque Revival style.

Base: The first story is dominated by the vehicular entrance, which is framed in cast iron and set in the center of a rusticated brownstone surround. Modest fish-scale and flame-shaped motifs ornament the cast-iron piers, transom bars and lintel. The vehicular entrance is a wood-panelled overhead door painted red. The pedestrian entrance is placed within the cast-iron frame on the west side of the building. The house watch window with historic wood sash is symmetrically placed on the east side of the frame. "Engine 36" is painted on the top panel of the cast-iron frame.

Upper stories: A brownstone molding separates the base from the upper stories. The second and third floors are faced in brick. Between the second and third stories is the identifying tablet listing the presiding Fire Department Officers and names N. LeBrun & Sons as the building's architects. Curved brownstone edges frame the building above the base, providing the effects of quoins and terminating in carved, knobbed finials at the fourth story gable.

At the second and third stories are tripartite windows with transoms; a single arched window is centered in the gable. Small one-over-one windows have been added to the east side of the second and third story to provide light and air for bathrooms. All the windows have historic wood sash.

Fourth story: The gable is the most detailed element of the composition, featuring a decorative brownstone gableboard, and a heavily-carved ovolo molding which forms the window's arch. The window has historic multi-pane wood sash. The gable itself is a stepped pattern, trimmed in brownstone and capped with a finial, set into mansard roof with multicolored slate tiles. The wrought-iron jib used for hauling hay to the attic storage room, remains in place above the gable window.

Several integral interior features are intact, such as the circular iron staircase, the brass sliding poles, the interior hose drying "tower," and the pressed-tin ceiling. (The interior is not included in this designation.)

- From the 1997 NYCLPC Landmark Designation Report

Fire Hook & Ladder Company No. 14

Harlem, Manhattan

Summary

Fire Hook & Ladder Company No. 14, built in 1888-89, was designed by the architectural firm of N. LeBrun & Sons in the Romanesque Revival style. Between the years of 1880 and 1895, N. LeBrun & Sons helped to define the Fire Department's expression of civic architecture, both functionally and symbolically, in more than 40 buildings. Hook & Ladder No. 14 is characteristic of N. LeBrun & Sons' numerous mid-block firehouses, reflecting the firm's attention to materials, stylistic detail, plan, and setting. Built on the site of an earlier volunteer fire company, and then a professional suburban company, this firehouse also represents nearly 150 years of the New York Fire Department's history. Since 1975, it has been the home of Fire Engine Co. No. 36.

The Fire Department of the City of New York

The origins of New York's Fire Department date to the city's beginning as the Dutch colony New Amsterdam. Leather fire buckets, first imported from Holland and later manufactured by a cobbler in the colony, were required in every household. Regular chimney inspections and the "rattle watch" patrol helped protect the colony during the Dutch period. By 1731, under English rule, two "engines" were imported from London and housed in wooden sheds in lower Manhattan.

The Common Council authorized a volunteer force in 1737, and the Volunteer Fire Department of the City of New York was officially established by an act of the state legislature in 1798. As the city grew, this force was augmented by new volunteer companies. Between 1800 and 1850, seven major fires occurred, leading to the establishment of a building code and the formation of new volunteer fire companies on a regular basis. The number of firemen grew from 600 in 1800 to more than 4,000 by 1865.

Intense rivalries among the companies developed, stemming in large part from the Volunteer Fire Department's role as a significant political influence in municipal affairs. The Tammany political machine was especially adept at incorporating the fire department into its ranks. Since the 1820s it was common knowledge that "a success in the fire company was the open sesame to success in politics."

During the peak years of Tammany's power, increasingly intense competition among companies began to hinder firefighting, creating public exasperation with the volunteer force. Brawls among firemen at the scene of fires and acts of sabotage among the companies became commonplace. In the 1860s, an alliance between the Republican controlled state legislature (which wanted to impair Tammany Hall's political control) and fire insurance companies (who wanted more efficient firefighting) played on this public sentiment to replace the volunteers with a paid force.

On March 30, 1865, the New York State Legislature established the Metropolitan Fire District, comprising New York and Brooklyn. This act abolished New York's Volunteer Fire Department and created the Metropolitan Fire Department, a paid professional force under the jurisdiction of the state. By the end of the year, the city's 124 volunteer companies with more than 4,000 men had retired or disbanded to be replaced by thirty-three engine companies and twelve ladder companies operated by a force of some 500 men.

With the creation of a professional Fire Department in 1865, improvements were immediate. Regular service was extended to 106th Street in Manhattan, with suburban companies further north, and its telegraph system was upgraded. Early in 1865 there were only 64 call boxes in New York, none of them located above 14th Street. Within the next year and a half, the number had increased to 187.3 Horse-drawn, steam-powered apparatus were required for all companies.

The firehouse crews were standardized at twelve men (as opposed to a total of up to 100 men per firehouse under the volunteer system), and the Department took on a serious, disciplined character.

In 1869, "Boss" William Marcy Tweed's candidate for New York State governor was elected, and he quickly regained control of the Fire Department through the Charter of 1870 (commonly known as the "Tweed Charter"). Only three years later, this charter was revoked when Tweed was sentenced to prison for embezzling millions from the city. Permanently under city control after 1870, the Fire Department (separated into a New York Department and a Brooklyn Department) retained its professional status and proceeded to modernize rapidly. While no new buildings were built until 1879-80 (the last one built prior to this was the Fireman's Hall in 18546), the companies continually invested in modern apparatus and new technologies.

Firehouse Function and Planning in the LeBrun Era

With the creation of the Metropolitan Fire Department in 1865 ? and the supposed removal of Tammany control of the companies ? the Common Council hoped to filter out remaining Tammany influence by banning any firehouse construction for five years.

The ban, for reasons unknown, lasted until 1879, when, under Fire Chief Eli Bates, the department embarked on a major campaign for new firehouse construction throughout the city, but especially in northern sections.

N. LeBrun & Sons designed all of the Fire Department's forty-two structures built between 1880 and 1895. It is not clear exactly why the LeBrun firm was commissioned by the Fire Department to serve as its sole architect during these years. Napoleon LeBrun had a personal interest in promoting the use of professional architects rather than contractors for municipal building projects. In 1879, LeBrun was the representative of the American Institute of Architects on the Board of Examiners of the Building Bureau of the Fire Department, a position he held for eighteen years.

This position may well have led to the commission by the Fire Department, which ultimately did set a standard for firehouse design in New York.

With the professionalization of the firefighting force in 1865, the spatial requirements of the firehouse were established.8 The ground floor functioned primarily as storage for the apparatus, and the second and third floors housed the dormitory, kitchen, and captain's office. While the basic function of the house had not changed by 1880 (and is essentially the same today), LeBrun is credited with standardizing the main program components, while introducing some minor, but important, innovations in the plan.

For example, when horses were first introduced into the system, they were stabled outside behind the firehouse. Valuable time was lost in bringing them inside to the apparatus. LeBrun's firehouses included horse stalls inside the building, at the rear of the apparatus floor, and some houses had special features related to the horses' care and feeding.

The LeBrun firehouses also neatly accommodated the necessity of drying the cotton hoses after each use, incorporating an interior hose-drying "tower" which ran the height of the building along one wall, thus economizing valuable space in the firehouse.

History of Hook & Ladder Company No. 14

Because northern Manhattan was sparsely populated in 1865, the Metropolitan Fire Department established suburban companies to serve that area. These companies, both engine and ladder, functioned slightly differently than their counterparts downtown. The suburban firefighters had a lighter work schedule and received less pay, and the companies were assigned hand-drawn apparatus instead of the horse-drawn steamers and trucks assigned to the regular companies. In October 1865, Suburban Ladder No. 14 was established at 120 East 125th Street, inheriting the property and equipment of the volunteer Mechanics No. 7." The city grew rapidly northward, and less than three years later, on January 1, 1868, the Fire Department closed all suburban companies.

Hook & Ladder No. 14 replaced Suburban Ladder No. 14. It continued to operate out of the old volunteer firehouse at 120

East 125th Street until 1888, when a new building was constructed in response to Harlem's growing population.

As reported in the Fire Department's Annual Report of 1889, the department recognized the need to prepare for the encroaching development of the city northward in Manhattan:

There is also imperative need of a number of additional companies north of One Hundred and Tenth Street, where no increase in the fire-extinguishing force has been made since the organization of the Department, to keep pace with the large growth in population and buildings.

The new structure for Hook & Ladder No. 14, designed by the architectural firm of N. LeBrun & Sons, was erected in 1888-89.13 In the first year in its new home, the company was staffed by twelve firemen and three horses for its hook and ladder truck; it responded to 146 alarms and fought 93 fires.

The structure was home to Hook & Ladder Company No. 14 until 1975. No. 14 relocated to 2282 Third Avenue, and Engine Company No. 36 relocated here from 1849 Park Avenue.

Built in the middle of the fifteen-year period in which the LeBrun firm designed for the Fire Department, Hook & Ladder No. 14 is representative of the firm's approach to firehouse design during a highly politicized period for the Fire Department and a time of intense urbanization for the city at large. The LeBrun era facade designs reflected the firehouses' surroundings in scale, materials, adherence to the street wall, and stylistically as well. Because the firehouse was home to the firemen, these designs project a certain domesticity within their functional character; this is particularly true for Hook & Ladder No. 14, as expressed in the mansard roof and attic gable.

While Hook & Ladder No. 14 reflects its context in scale and composition, but is also distinguished as both a civic and a utilitarian structure. East 125th Street is comprised mainly of commercial buildings built near the end of the nineteenth century.

The Queen Anne-Romanesque Revival Mount Morris Bank (Lamb & Rich, 1883-85, 1889-90, designated New York City Landmark) at East 125th Street and Park Avenue is the grandest of these, although it is now in a state of serious neglect. The surrounding residential neighborhood includes numerous rowhouses from the same period, reflecting Harlem's early development as an affluent community. The Hook & Ladder No. 14 is a significant reminder of that period, and along with the Mt. Morris Watch Tower (1855, designated New York City Landmark) and the Harlem Courthouse (Thom & Wilson, 1891-93, designated New York City Landmark), is an important symbol of the city's municipal development in the nineteenth century.

N. LeBrun & Sons, Architects

Napoleon Eugene Charles LeBrun (1821-1901) was born to French immigrant parents in Philadelphia. At fifteen years of age he was placed in the office of classicist Thomas Ustick Walter (1804-1887), where he remained for six years.

LeBrun began his own practice in 1841 in Philadelphia where he had several major commissions ? including the Cathedral of SS. Peter and Paul (1846-64) and the Academy of Music (1852-57) - before moving to New York in 1864. His Second Empire Masonic Temple competition submission of 1870 did much to establish his reputation in New York. In the same year his son Pierre joined him and the firm became Napoleon LeBrun & Son in 1880. In 1892 the firm became Napoleon LeBrun & Sons in recognition of his youngest son, Michel. All three were active members of the American Institute of Architects.

Napoleon LeBrun was first commissioned by the Fire Department of the City of New York in 1880. Until 1895, N. LeBrun & Sons designed more than 40 buildings for the Fire Department throughout Manhattan, including many firehouses, a warehouse, and a fire pier.

The firm's fifteen-year building campaign resulted in an average of two to three firehouses each year. In some cases, nearly identical buildings were erected; Hook & Ladder No. 14 has a twin in Engine Company No. 56 at 120 West 83rd Street (1888-89, located in the Upper West Side/Central Park West Historic District).

Most of the designs used classical detailing and overall symmetry (in part dictated by the large vehicular entrance on a narrow lot), but provided a wide range of aesthetic expression.

The firm created two large, elaborate buildings for the Fire Department during this period: the Fire Department Headquarters at 157-159 East 67th Street (now Engine Company No. 39/Ladder Company No. 16, 1884-86) and Engine Company No. 31, 87 Lafayette Street (1895, a designated New York City Landmark). The Headquarters building is a strong expression of the Romanesque Revival style, and in the years following its completion, several smaller houses were designed in a subdued version of the style. Hook & Ladder No. 14 is one example.

Engine Company No. 31, the firm's best known firehouse design, is the least representative of its tenure with the Fire Department and marks a transition between the restrained, classical elegance of the majority of its firehouses and the increasingly monumental designs of other architects which followed at the turn of the century.

Engine Company No. 31 is a freestanding structure for a triple engine company modeled on sixteenth-century Loire Valley chateaux. It was a distinct departure from the firm's usual "storefront" design and is considered the firm's most impressive civic design. Also of note was the firm's acclaimed Hook & Ladder Company No. 15 at Old Slip (1885, demolished), which was designed in the style reminiscent of a seventeenth-century Dutch house.

While they are best known in New York City for the firehouses, the LeBruns designed several churches including the Church of the Epiphany (1870, demolished), Saint John-the-Baptist (1872), 211 West 30th Street, and St. Mary-the-Virgin (1894-95, a designated New York City Landmark), 133-145 West 46th Street. At the turn of the century, N. LeBrun & Sons achieved renown for office building design in Manhattan, most notably the home office of the Metropolitan Life Building at 1 Madison Avenue (1890-92, and annex tower, 1909, designated New York City Landmark) and the Home Life Insurance Company Building, 256-257 Broadway (1892-94, a designated New York City Landmark).

Building Description

Hook & Ladder Company No. 14 is a four-story brick and stone structure. Through its composition, colors, and subtle texture, the building expresses the Romanesque Revival style.

Base: The first story is dominated by the vehicular entrance, which is framed in cast iron and set in the center of a rusticated brownstone surround. Modest fish-scale and flame-shaped motifs ornament the cast-iron piers, transom bars and lintel. The vehicular entrance is a wood-panelled overhead door painted red. The pedestrian entrance is placed within the cast-iron frame on the west side of the building. The house watch window with historic wood sash is symmetrically placed on the east side of the frame. "Engine 36" is painted on the top panel of the cast-iron frame.

Upper stories: A brownstone molding separates the base from the upper stories. The second and third floors are faced in brick. Between the second and third stories is the identifying tablet listing the presiding Fire Department Officers and names N. LeBrun & Sons as the building's architects. Curved brownstone edges frame the building above the base, providing the effects of quoins and terminating in carved, knobbed finials at the fourth story gable.

At the second and third stories are tripartite windows with transoms; a single arched window is centered in the gable. Small one-over-one windows have been added to the east side of the second and third story to provide light and air for bathrooms. All the windows have historic wood sash.

Fourth story: The gable is the most detailed element of the composition, featuring a decorative brownstone gableboard, and a heavily-carved ovolo molding which forms the window's arch. The window has historic multi-pane wood sash. The gable itself is a stepped pattern, trimmed in brownstone and capped with a finial, set into mansard roof with multicolored slate tiles. The wrought-iron jib used for hauling hay to the attic storage room, remains in place above the gable window.

Several integral interior features are intact, such as the circular iron staircase, the brass sliding poles, the interior hose drying "tower," and the pressed-tin ceiling. (The interior is not included in this designation.)

- From the 1997 NYCLPC Landmark Designation Report

Ladder 14 Firefighters rescue two people 'ready to jump' from burning Harlem brownstone

By Kerry Burke and John Lauinger DAILY NEWS STAFF WRITERS Feb 01, 2010 | 11:02 PM

FDNY was able to save two people who were dangling from the window ledge after a fire broke out at a Harlem brownstone Monday.

Firefighters rescued two people desperately perched on window ledges as fire raged on the top floor of a Harlem brownstone Monday, officials said.

The stranded man and woman were screaming for help as firefighters arrived at the abandoned five-story brownstone at Madison Ave. and E. 127 St. at about 4:21 p.m. "There were two people hanging from window ledges," said FDNY Deputy Chief Jim Hodgens. "They were ready to jump." Firefighters scurried up a massive tower ladder and plucked the two people from the window ledges as thick, black smoke billowed around them.

"She jumped into my arms as quick as she could," firefighter Artie Kunz, of the FDNY's Ladder 14, said of the rescued woman. "It made me feel great." People who crowded on the street to watch the drama unfold were stunned by the nick-of-time rescue. "When they put up a ladder and pulled her off, a roar went up from the crowd," said Derrick Tate, a retired Corrections Department officer. "It was glorious."

Firefighter Al Grdovich said the woman thanked God as she was carried to safety. "I believe God was on her side," Grdovich said. Firefighters also rescued a woman who had gone into cardiac arrest from inside the building's fifth floor. "They were trying to revive her on the sidewalk out front," Tate recalled. "It didn't look good." Officials said the woman, described as being in her 50s, was taken to Harlem Hospital in critical condition.

Neighbors said people had been squatting inside the abandoned building. There was a second fire on E. 127 St. near 10th Ave. at roughly the same time Monday afternoon. That blaze was quickly brought under control, and no one was injured, officials said.

By Kerry Burke and John Lauinger DAILY NEWS STAFF WRITERS Feb 01, 2010 | 11:02 PM

FDNY was able to save two people who were dangling from the window ledge after a fire broke out at a Harlem brownstone Monday.

Firefighters rescued two people desperately perched on window ledges as fire raged on the top floor of a Harlem brownstone Monday, officials said.

The stranded man and woman were screaming for help as firefighters arrived at the abandoned five-story brownstone at Madison Ave. and E. 127 St. at about 4:21 p.m. "There were two people hanging from window ledges," said FDNY Deputy Chief Jim Hodgens. "They were ready to jump." Firefighters scurried up a massive tower ladder and plucked the two people from the window ledges as thick, black smoke billowed around them.

"She jumped into my arms as quick as she could," firefighter Artie Kunz, of the FDNY's Ladder 14, said of the rescued woman. "It made me feel great." People who crowded on the street to watch the drama unfold were stunned by the nick-of-time rescue. "When they put up a ladder and pulled her off, a roar went up from the crowd," said Derrick Tate, a retired Corrections Department officer. "It was glorious."

Firefighter Al Grdovich said the woman thanked God as she was carried to safety. "I believe God was on her side," Grdovich said. Firefighters also rescued a woman who had gone into cardiac arrest from inside the building's fifth floor. "They were trying to revive her on the sidewalk out front," Tate recalled. "It didn't look good." Officials said the woman, described as being in her 50s, was taken to Harlem Hospital in critical condition.

Neighbors said people had been squatting inside the abandoned building. There was a second fire on E. 127 St. near 10th Ave. at roughly the same time Monday afternoon. That blaze was quickly brought under control, and no one was injured, officials said.

Engine 35 firehouse 223 E 119th Street Harlem 4th/5th Division, 11th/12th Battalion "Still First"

Engine 35 organized 223 E 119th Street former firehouse volunteer Columbus Engine 35 1868

Engine 35 moved to 209 E 122nd Street at Suburban Engine 37 1889

Engine 35 moved to new firehouse 223 E 119th Street 1891

Engine 35 moved to new firehouse 2282 3rd Avenue with Thawing Apparatus 1 1974

Engine 35 - 223 E 119th Street original volunteer firehouse - built 1861:

223 E 119th Street firehouse - built 1891:

2282 3rd Avenue firehouse - built 1974:

Engine 35:

Engine 35:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pgT3wfe5hOo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nnxme4VqWx8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mUarTKD0L6k

Engine 35 Department Medals:

WILLIAM H. BEHLER FF. ENG. 35 JAN. 13, 1895 1896 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

Fireman William H. Behler, of Engine Company No. 35, is awarded to him for a rescue described as follows in the report for that year:

?Fireman William H. Behler, of Engine Company No. 35, rescued Mrs. Carmela Amaro and child at the fire No. 409 East One Hundred and Twelfth Street, Station 737, at 8:53 A.M., on the 31st of January, under the following circumstances: Mrs. Amaro appeared at the fourth-story window, front, shrieking wildly for help, as she clasped a three-month-old child to her breast. She could not reach the fire-escape from the window at which she stood on account of smoke and heat, and Hook and Ladder Company No. 14 had not yet arrived. The woman was about to jump to the street when Fireman Behler appeared at the fourth-story window of No. 407 , which is next to where the woman stood. He leaned out of the window and, while some citizens held him by the legs, reached over to where the woman stood. She passed her child to him and then swung herself into his arms, and Behler landed both safely on the floor of the adjoining flat. The chief of the Eleventh Battalion, in reporting the occurrence says: ?I consider the prompt action of Fireman Behler prevented serious consequences and was a personal risk, for which I recommend that his name be placed on the Roll of Merit?? - Report of the Fire Department of the City of New York

RICHARD NITSCH FF. ENG. 35 JAN. 29, 1901 1903 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

Role of Merit ? Rescues at Personal Risk in the Line of Duty ? By Fireman 1st Grade Richard Nitsch, Engine 35. At the fire premises No 402 East One Hundred and Eighteenth Street, on the morning of January 29, Fireman Nitsch, at personal risk, rescued Mrs. George Le Piemme, age forty, from a rear room on the second floor, which was so densely charged with heat, smoke and flame that, after discovering her unconscious on the floor, her clothing afire, in order to effect her rescue it was necessary for him to crawl to the stairway, dragging his human burden after him, where, assisted by a comrade, the woman was conveyed to the street, whence, considerably burned, she was removed to Harlem Hospital for treatment.

WILLIAM WEBER FF. ENG. 35 MAY 14, 1904 TREVOR-WARREN

?The names of Fireman first grade William Weber, Engine Company 35, Andrew W. Zwisler, Engine Company 14, and William M. Carter, Hook and Ladder Company 14, were ordered placed on the Roll of Merit, Class A, for meritorious action at fire at No. 2001 Third Avenue, Statin 697, on May 14, 1904. The fire was found to be rapidly burning in the halls and stairways of the building, and heavily charged with smoke, and occupants of premises hanging out of windows. Fireman Weber descended a 35 foot ladder to the 4th floor and assisted Mrs. Tessie Klebs and her eighteens-old baby, also George Florre, down the ladder. While descending the ladder, Fireman Weber was informed by citizens from the street that there was a woman on the third floor. He entered the room, which was heavily charged with heat and smoke, and, crawling on his hands and knees to the middle of the room, found Mrs. H. Eyl on the floor in an unconscious condition. He attempted to drag her to window, but being nearly overcome by heat and smoke he was compelled to return to the window, where he met Fireman first grade A. W. Zwisler, who assisted in dragging Mrs Eyl, (who was a very heavy woman) to the window, where she was taken down the ladder to the street. At the same time, Fireman first grade William M. Carter, Hook and Ladder Company 14, ascended by scaling ladder to fourth floor on Third Avenue side of the building and entered a room where he found Josephine Eyl, aged 18 months, on fire, and carried her to the window and passed her to occupants of adjoining building. The fire in the meantime had gained considerable headway in all the halls and stairways on the upper three floors, causing great heat and stifling smoke and all means of escape for occupants cut off.? Report of the Fire Department of the City of New York for the Year 1902.

FRANK A. TOOMEY LT. ENG. 35 MAR. 5, 1933 1934 DEPARTMENT

WILLIAM F. MORAN FF. ENG. 35 NOV. 16, 1963 1964 MC ELLIGOTT

JOHN J. MC CORMICK LT. ENG. 35 OCT. 23, 1964 1965 EMERALD

EDMOND CALO, JR. FF. ENG. 35 NOV. 7, 1984 1985 LAUFER

Engine 35 LODDs:

FIREFIGHTER JOHN DEGNAN ENGINE 35 April 7, 1931

Fireman John Degnan of Engine 35 was killed and four other firemen were injured while responding to a fire. The accident resulted from efforts to avert a collision with a delivery truck on East 123rd Street. The driver of the truck turned his wheels away from the fire truck and fainted. Engine 35 slammed into the truck, a limousine and an elevated pillar throwing everybody to the street. Captain Martin Tarpey, Firemen John Degnan and John Coddington were on the side that hit the elevated pillar. Captain Tarpey lost his leg, Coddington received a fractured skull and a brain concussion but both recovered from their injuries. Fireman Degnan became a fireman in 1915 and was single. (From "The Last Alarm")

CAPTAIN WILLIAM J. BRADY ENGINE 35 February 8, 1952

Capt. William J. Brady - Engine 35 - 16-year veteran died as a result of injuries sustained while operating at a fire on January 30th.

FIREFIGHTER RICHARD G. SALE ENGINE 35 June 19, 1986

Pre-FDNY volunteer history:

Columbus Engine 35 - 1807-1865

Engine 35 organized 223 E 119th Street former firehouse volunteer Columbus Engine 35 1868

Engine 35 moved to 209 E 122nd Street at Suburban Engine 37 1889

Engine 35 moved to new firehouse 223 E 119th Street 1891

Engine 35 moved to new firehouse 2282 3rd Avenue with Thawing Apparatus 1 1974

Engine 35 - 223 E 119th Street original volunteer firehouse - built 1861:

223 E 119th Street firehouse - built 1891:

2282 3rd Avenue firehouse - built 1974:

Engine 35:

Engine 35:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pgT3wfe5hOo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nnxme4VqWx8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mUarTKD0L6k

Engine 35 Department Medals:

WILLIAM H. BEHLER FF. ENG. 35 JAN. 13, 1895 1896 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

Fireman William H. Behler, of Engine Company No. 35, is awarded to him for a rescue described as follows in the report for that year:

?Fireman William H. Behler, of Engine Company No. 35, rescued Mrs. Carmela Amaro and child at the fire No. 409 East One Hundred and Twelfth Street, Station 737, at 8:53 A.M., on the 31st of January, under the following circumstances: Mrs. Amaro appeared at the fourth-story window, front, shrieking wildly for help, as she clasped a three-month-old child to her breast. She could not reach the fire-escape from the window at which she stood on account of smoke and heat, and Hook and Ladder Company No. 14 had not yet arrived. The woman was about to jump to the street when Fireman Behler appeared at the fourth-story window of No. 407 , which is next to where the woman stood. He leaned out of the window and, while some citizens held him by the legs, reached over to where the woman stood. She passed her child to him and then swung herself into his arms, and Behler landed both safely on the floor of the adjoining flat. The chief of the Eleventh Battalion, in reporting the occurrence says: ?I consider the prompt action of Fireman Behler prevented serious consequences and was a personal risk, for which I recommend that his name be placed on the Roll of Merit?? - Report of the Fire Department of the City of New York

RICHARD NITSCH FF. ENG. 35 JAN. 29, 1901 1903 JAMES GORDON BENNETT

Role of Merit ? Rescues at Personal Risk in the Line of Duty ? By Fireman 1st Grade Richard Nitsch, Engine 35. At the fire premises No 402 East One Hundred and Eighteenth Street, on the morning of January 29, Fireman Nitsch, at personal risk, rescued Mrs. George Le Piemme, age forty, from a rear room on the second floor, which was so densely charged with heat, smoke and flame that, after discovering her unconscious on the floor, her clothing afire, in order to effect her rescue it was necessary for him to crawl to the stairway, dragging his human burden after him, where, assisted by a comrade, the woman was conveyed to the street, whence, considerably burned, she was removed to Harlem Hospital for treatment.

WILLIAM WEBER FF. ENG. 35 MAY 14, 1904 TREVOR-WARREN

?The names of Fireman first grade William Weber, Engine Company 35, Andrew W. Zwisler, Engine Company 14, and William M. Carter, Hook and Ladder Company 14, were ordered placed on the Roll of Merit, Class A, for meritorious action at fire at No. 2001 Third Avenue, Statin 697, on May 14, 1904. The fire was found to be rapidly burning in the halls and stairways of the building, and heavily charged with smoke, and occupants of premises hanging out of windows. Fireman Weber descended a 35 foot ladder to the 4th floor and assisted Mrs. Tessie Klebs and her eighteens-old baby, also George Florre, down the ladder. While descending the ladder, Fireman Weber was informed by citizens from the street that there was a woman on the third floor. He entered the room, which was heavily charged with heat and smoke, and, crawling on his hands and knees to the middle of the room, found Mrs. H. Eyl on the floor in an unconscious condition. He attempted to drag her to window, but being nearly overcome by heat and smoke he was compelled to return to the window, where he met Fireman first grade A. W. Zwisler, who assisted in dragging Mrs Eyl, (who was a very heavy woman) to the window, where she was taken down the ladder to the street. At the same time, Fireman first grade William M. Carter, Hook and Ladder Company 14, ascended by scaling ladder to fourth floor on Third Avenue side of the building and entered a room where he found Josephine Eyl, aged 18 months, on fire, and carried her to the window and passed her to occupants of adjoining building. The fire in the meantime had gained considerable headway in all the halls and stairways on the upper three floors, causing great heat and stifling smoke and all means of escape for occupants cut off.? Report of the Fire Department of the City of New York for the Year 1902.

FRANK A. TOOMEY LT. ENG. 35 MAR. 5, 1933 1934 DEPARTMENT

WILLIAM F. MORAN FF. ENG. 35 NOV. 16, 1963 1964 MC ELLIGOTT

JOHN J. MC CORMICK LT. ENG. 35 OCT. 23, 1964 1965 EMERALD

EDMOND CALO, JR. FF. ENG. 35 NOV. 7, 1984 1985 LAUFER

Engine 35 LODDs:

FIREFIGHTER JOHN DEGNAN ENGINE 35 April 7, 1931

Fireman John Degnan of Engine 35 was killed and four other firemen were injured while responding to a fire. The accident resulted from efforts to avert a collision with a delivery truck on East 123rd Street. The driver of the truck turned his wheels away from the fire truck and fainted. Engine 35 slammed into the truck, a limousine and an elevated pillar throwing everybody to the street. Captain Martin Tarpey, Firemen John Degnan and John Coddington were on the side that hit the elevated pillar. Captain Tarpey lost his leg, Coddington received a fractured skull and a brain concussion but both recovered from their injuries. Fireman Degnan became a fireman in 1915 and was single. (From "The Last Alarm")

CAPTAIN WILLIAM J. BRADY ENGINE 35 February 8, 1952

Capt. William J. Brady - Engine 35 - 16-year veteran died as a result of injuries sustained while operating at a fire on January 30th.

FIREFIGHTER RICHARD G. SALE ENGINE 35 June 19, 1986

Pre-FDNY volunteer history:

Columbus Engine 35 - 1807-1865

mack said:

Engine companies assigned 1963 International Harvester 1000 GPM pumpers: 35, 53, 58, 59, 69, 73, 91, 94, 283 and 290.

Those 10 rigs were an experiment to see how well commercial chassis apparatus would hold up in NYC. Four of the 10 would wind up getting destroyed: E283's rig was hit by a heavy truck on Linden Blvd., E91's (and L40's 1963 Seagrave tiller) was crushed in a collapse on 116th St., E94's rig caught fire, and E294's rig caught fire inside quarters. - per Gman

1964 Harlem 5th alarm 116th Street - destroyed Engine 91 and Ladder 40 apparatus:

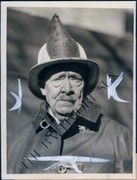

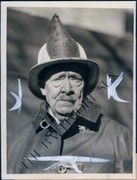

Chief Edward Franklin Croker - Chief of Department - 1899-1911

?I have no ambition in this world but one, and that is to be a firefighter The position may, in the eyes of some, appear to be a lowly one; but we who know the work which the firefighter has to do believe that his is a noble calling.There is an adage which says that, "Nothing can be destroyed except by fire." We strive to preserve from destruction the wealth of the world which is the product of the industry of men, necessary for the comfort of both the rich and the poor. We are defenders from fires of the art which has beautified the world, the product of the genius of men and the means of refinement of mankind. But, above all; our proudest endeavor is to save lives of men-the work of God Himself. Under the impulse of such thoughts, the nobility of the occupation thrills us and stimulates us to deeds of daring, even at the supreme sacrifice. Such considerations may not strike the average mind, but they are sufficient to fill to the limit our ambition in life and to make us serve the general purpose of human society.? - Chief Croker

?Firemen are going to get killed. When they join the department they face that fact. When a man becomes a fireman his greatest act of bravery has been accomplished. What he does after that is all in the line of work. They were not thinking of getting killed when they went where death lurked. They went there to put the fire out, and got killed. Firefighters do not regard themselves as heroes because they do what the business requires.? - Chief Croker

Edward Franklin Croker - Find-A-Grave Memorial

It is difficult to sum up the career of Edward Franklin Croker in this limited amount of space. Appointed to the FDNY on June 22, 1884 at the age of twenty-one, he shocked everyone with his promotion to Assistant Foreman (now called Lieutenant) just forty-seven days later and with equal speed to Foreman (today's Captain) on February 25, 1885. This rapid advancement was said to have been for one reason only; that he was the nephew of the most powerful political figure in New York City at the time, Richard Croker, head of Tammany Hall (who served as a fire commissioner 1883-1887.) And while this might be true, the fact was that over the next twenty-seven years, Chief Croker proved himself, time and time again, to be an outstanding firefighter and leader.

On January 22, 1892 Foreman Croker became Battalion Chief Croker. Being named Chief of Department on May 1, 1899, the specter of nepotism was cast upon him but he went on to fulfill his role with extreme diligence. He was the first Chief of Department who did not serve during the volunteer period. He was also the first Chief to use an automobile to respond to alarms.

In 1902, Chief Croker returned to work only several days into a two-month vacation. A vacation of such length was unusual but deemed justified for the hard-working Chief. In granting it, Commissioner Thomas Sturgis re-assigned other chiefs within the Department to cover Croker's absence. But when Croker returned to work less than two weeks later and sent the chiefs back to the original assignments, the Commissioner saw it as an overstepping of bounds and a rescinding of the orders of a higher authority. Sturgis relieved Croker of command and preferred formal charges. A two-year court battle ensued with a final decision in Croker's favor resulting in his re-instatement.