Engine 7/Ladder 1/Battalion 1 (continued)

ENGINE 7/LADDER 1 MEDALS

JAMES G. BROWN FF. LAD. 1 JAN. 9, 1912 1913 BONNER

FF Brown was awarded the Bonner Medal for rescuing Capt. Bass from the 4th floor of the Equitable Building, 120 Broadway. Brown was on the 4th floor of the building when the interior walls collapsed throwing FF Brown, Chief Walsh and Capt. Bass in different directions. FF Brown was thrown through a door into another wing of the building. Hearing cries for help, Brown made his way back to where Capt. Brown had been thrown and found him with burns on his face and hands. Capt. Brown was also partially buried in the debris. FF Brown dragged Capt. Bass to a window and left him. FF Brown then tried to find Chief Walsh back in the collapse area. Unable to find Chief Walsh, FF Brown sought help from Ladder 8. With help from Ladder 8, FF Brown assisted Capt. Bass down a 35 foot ladder. Unfortunately, Capt. Bass later died from his injuries. Chief Walsh also died during the collapse.

EQUITABLE BUILDIING FIRE:

The Equitable Building Fire

The Equitable Building Fire

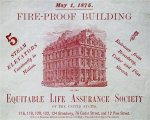

In its day, no other private business building in the world could compare with the Equitable Life Assurance Building in New York City in respect to the magnitude of the monetary interests assembled under its roof. Several billion dollars in securities, stocks, bonds and cash were stored in its huge basement vaults. Considered by many as the world’s first skyscraper, the eight-story building at 120 Broadway was completed in 1870.

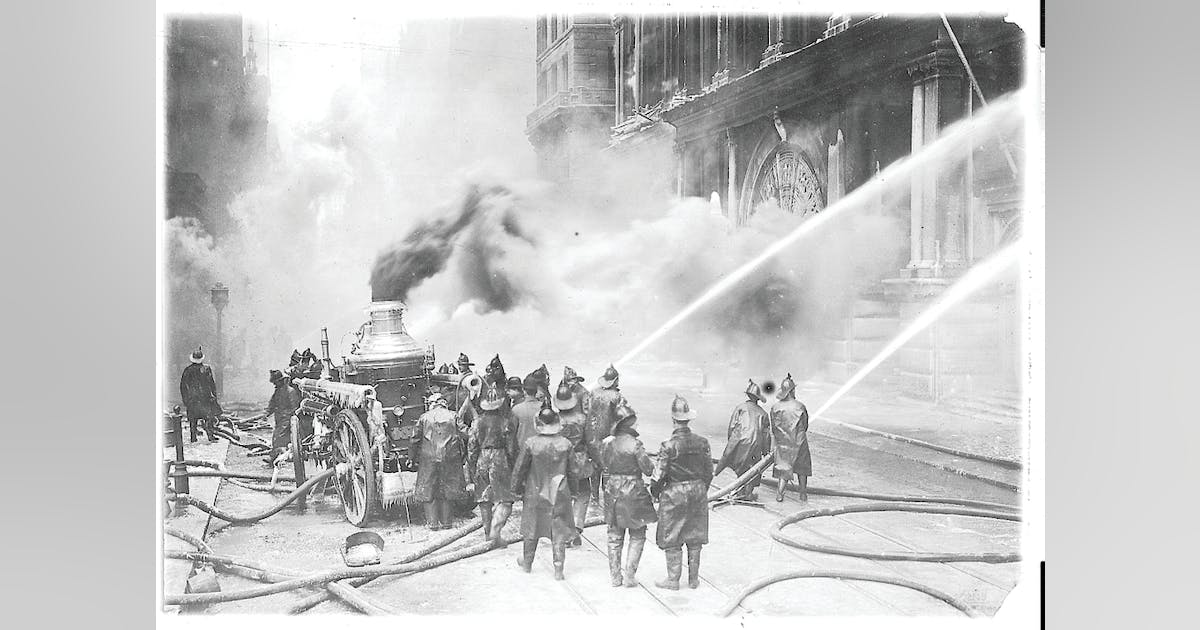

Powerful handlines are directed into the blazing building during the early stages of the fire.

In its day, no other private business building in the world could compare with the Equitable Life Assurance Building in New York City in respect to the magnitude of the monetary interests assembled under its roof. Several billion dollars in securities, stocks, bonds and cash were stored in its huge basement vaults. Considered by many as the world’s first skyscraper, the eight-story building at 120 Broadway was completed in 1870. It was the first office building to feature passenger elevators. When it opened for business it held the record as the world’s largest building at 130 feet and held that record for 14 years.

A composite structure, the Equitable Building consisted of five buildings erected at different times. It occupied the entire square block bordered by Broadway, Nassau, Cedar and Pine streets. The buildings had undergone many alterations, including openings on most floors between structures, allowing uninhibited travel from one area to another. The main tenant and owner was the Equitable Life Assurance Society. Equitable’s president, Henry Baldwin Hyde, started a Lawyers’ Club within the building that grew to more than 1,800 members. A large law library featured 40,000 volumes aside from a separate insurance library. The Mercantile Safe Deposit Co., Union Pacific and many other professionals also had offices within the large building. In 1888, the Cafe Savarin opened, occupying a large space in the Broadway and Pine Street corner of the building. The cafe also served the kitchen of the Lawyers’ Club and three big dining rooms.

On Jan. 9, 1912, at 5:18 A.M., a building employee discovered a fire in the basement of 12 Pine St. A wastepaper basket, chair and desk in the watchman’s tiny office were burning briskly. He went to summon help. The fire traveled down a hallway to a large shaft containing two elevators and 11 dumbwaiters that served the Lawyers’ Club and the Cafe Savarin from the eighth-floor kitchen. There were direct openings on each floor from the cellar to roof, with the exception of the fourth floor.

Employees attempted to place a standpipe into operation, but stretched short. Finally, an excited employee told a policeman of the fire and 16 minutes after the fire had been discovered, Box 24 was transmitted. It sent four engines, two ladders, two battalion chiefs and the deputy chief of the First Division out into the bitter-cold Manhattan morning.

Engine 6, first in, took a hydrant2½ minutes after receiving the alarm and immediately stretched into the cellar and began operating. The companies made good progress in the cellar, unaware of the fire on the floors above them. At 5:55, Deputy Chief John Binns received reports of extension on the floors above and transmitted second and third alarms. This brought Chief of Department John Kenlon and Fire Commissioner Joseph Johnson to the scene.

Eight companies had entered the building and operated on the second, third, fourth and fifth floors for nearly a half-hour. Sixty-five-mph winds were whipping the fire out of control. Structural iron and steel supports were exposed to the fierce heat and were ready to buckle. At 6:35, after calling fourth and fifth alarms, Kenlon ordered everyone out of the building.

Because of the early hour, the only people in the building were cleaners, restaurant employees, watchmen, heating engineers and several bank employees. The rapidly extending fire and clouds of thick smoke filled the large building, cutting many people off from their exits. Despite the relatively low number of people inside, firemen would have numerous rescues to make. As the smoke and fire conditions worsened, three waiters from the Cafe Savarin took the elevator to the top floor, but flames drove them to the roof.

By now, 22 engines, two water towers and 10 trucks were working. Water was freezing in the air as streams were directed toward the raging flames. Ice was forming on everything in and around the burning building. The waiters became visible on the roof and Kenlon ordered a rescue attempt to commence. Using scaling ladders, Engineer of Steamer Charles W. Rankin of Engine 33 and Fireman Francis Blessing, Kenlon’s chauffeur, began working their way toward the men trapped on the mansard roof. This path proved to be nearly impassable due to copingstones that extended four feet from the building’s face.

As the ladder team tried to work around the obstruction, another four-man team raced to the 10-story building across the street. Firemen James F. Molloy of Engine 32 climbed out onto the edge of the roof. While he was being held, he leaned out as far as he could and fired a rope-rifle shot across to the trapped men. The small line, with a larger rope attached, was quickly pulled across by the waiters and tied off. As this rope was made taut, a huge flame shot from the burning building and burned the rope away in seconds. A dense cloud of smoke covered the entire top of the building for a few moments. The victims huddled on a small piece of coping as the roof they had been standing on moments before had fallen away as the interior of the building collapsed in on itself.

Rankin held tightly as the collapsing building shook violently. Blessing straddled an aerial ladder and slid to safety. Above them, the waiters lost their battle with the flames and jumped to their deaths. Rankin then worked his way to safety.

Inside the building was Battalion Chief William Walsh, who had led a group of 14 firemen up a ladder to complete searches on the fourth floor. A few minutes later the call to leave the building was given. As Walsh, Captain Charles Bass of Engine 4, Fireman James G. Brown of Ladder 1 and several other men were leaving the fourth floor the building caved in with a loud roar. Most of the firemen escaped, but several – including Walsh and Bass – were buried in the rubble.

Brown was hurled through a door into another wing of the building by the air pressure of the collapse. He immediately returned to where he knew the fire officers were trapped and began digging toward the sound of Bass’ weakening voice somewhere below. Brown found the severely injured and unconscious captain, dug him clear and carried him across the flaming debris pile to a ladder, where he handed him off to members of Ladder 8. A squad of firemen then descended on the collapse area and tried to locate Walsh in the rubble.

At the time of the fire, William Giblin, president of the Mecantile Savings Deposit Co., had gone to his office in the cellar to safeguard securities entrusted to his firm. The office windows, looking out on the Broadway sidewalk, were protected with a screen of bowed-out steel bars two inches in diameter. Giblin, two clerks named Peck and Siebert and watchmen William Campion and William Sheehan were busy in the office as the flames began eating into the inner walls. When the building caved in, Peck and Siebert fled through a door to Cedar Street. But then the door slammed shut and the warped frame locked it fast. The burning debris from above was piled about the vault like coal in a furnace.

Fire Commissioner Johnson and a department chaplain, Father Vincent de Paul McGean, were standing nearby and heard the cries of help from Giblin and Sheehan. Pressed close to the bars, Giblin and Sheehan were forced into a crouch by the fallen ceiling. Rankin and Fireman James Dunn of Engine 6 moved to the window and began sawing the bars in hopes of freeing the trapped men.

With a major fire and building collapse and men missing, Kenlon took historic action – the first borough call in FDNY history was transmitted, calling Brooklyn companies to the Manhattan fire. Learning that Brooklyn units would be responding, Police Commissioner Rhinelander Waldo (who had resigned as fire commissioner shortly after the deadly Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911), who was at the fire, ordered police officers to shut down the Brooklyn Bridge to facilitate the response. Minutes later, a long line of Brooklyn engines and trucks, each steam engine trailing a line of black smoke from its boiler, rolled straight across the bridge into Manhattan.

Nine engines, four hook and ladder trucks, a water tower, a searchlight engine and all the associated hose tenders rolled into the scene under the command of Chief Thomas Lally. The Brooklyn chief also brought an additional two deputies and nine more battalion chiefs with him to the scene.

Seneca Larke Jr., with the rank of engineer of steamer, had been running the searchlight engine, a rig invented by then-Chief of Department Edward F. Croker 10 years earlier. The rig featured large theatrical spotlights to aid firefighters working at night. With daylight breaking, Larke left his searchlight and volunteered his services to Kenlon. He explained that as a former ironworker he knew techniques that would enable him to do the job. Although reluctant to put the 37-year-old father of six into such a hazardous position, the chief agreed.

With a new saw and a number of blades, Larke relieved Rankin and Dunn, who had little success thus far. Larke lay on his stomach by the barred window and began cutting. At this fire, where an estimated 10 to 15 million gallons of water were used, water was pouring down onto Larke by the barrelful, freezing as it fell. Broken stones, glass, flaming embers, and debris fell on Larke and Father McGean, who had taken a position next to the prostrate fireman to give last rites to the imprisoned if the rescue failed.

Firefighters directed a hose stream into the cellar from time to time to control fire near the trapped men. Larke talked to Giblin, encouraging him as he worked to get through the bars. After nearly an hour, the first bar was cut free, but the opening was not large enough. Larke continued cutting, stopping only to change worn or broken saw blades – an interruption that was necessary 15 times. A large stone fell on Larke’s back, momentarily paralyzing him. Despite orders from both the chief and the commissioner to withdraw, Larke refused to stop cutting. Dunn had stayed nearby to help bend the bars back and chip away the ice from Larke’s rubber coat so his arms could move freely.

The rescue operation was almost an hour-and a-half old when Giblin told Larke that Campion was dead. Father McGean began his prayers as Larke sawed with renewed vigor. After nearly a half-hour more, the second bar gave way and was pulled clear. Larke called for help. Giblin and Sheehan were pulled to safety and hurried to a nearby hospital. Larke was also hospitalized.

The firefighting continued for many long hours. The rescue work was done, but the flames had to be controlled before firemen could safely venture in and begin recovering the dead, imprisoned in the ice covered tomb and to also recover the valuables still inside the building’s safes.

World financial markets were in a near panic as word spread that billions of dollars in stocks, bonds and securities could have been lost at the fire. In London, stocks took sharp losses as exaggerated accounts of the fire caused sell-offs of many stocks, including Union Pacific. New York bankers tried to calm fears and prevent a worldwide financial meltdown. On Jan. 11, under a guard of 150 policemen and 50 Burns detectives covering every possible approach to the site, officers and clerks of the Equitable Trust Co. and Mercantile Trust Co. removed $375 million in securities and $10 million in cash from the ice-coated vaults. On Feb. 4, the procedure was repeated as another large safe was located in the rubble. Securities valued at $282 million were additionally recovered.

On Jan. 13, four days after the fire started, workers located the body of the missing chief. It took an additional four hours of difficult work under the direction of Binns and Battalion Chief “Smoky Joe” Martin, for workers to completely uncover the chief. Firemen moved in and in a solemn procession, including 50 men from the Second Division (Walsh’s command), removed Walsh’s body and carried him from the frozen ruins. The following day, after eight hours of dangerous work, the body of Campion, his hand still frozen to an iron bar, was carefully removed from the cellar. On Nov. 16, 1912, Bass died from injuries received in the collapse.

New York has witnessed many fires and many great rescues, but it is doubtful that in the days of horses and wooden ladders that any surpassed the acts of heroism performed at the Equitable Building fire.

Author’s note:

This is an expanded version of my first published article that appeared in WNYF, the official FDNY magazine, in 1988. There were several small historical errors in the original that I have corrected in this version.

PAUL HASHAGEN, a

Firehouse® contributing editor, is a retired FDNY firefighter who was assigned to Rescue 1 in Manhattan. He is also an ex-chief of the Freeport, NY, Fire Department. Hashagen is the author of

FDNY: The Bravest, An Illustrated History 1865-2002, the official history of the New York City Fire Department, and other fire service books. His latest novel,

Fire of God, is available at dmcfirebooks.com.

HONORED FOR HEROISM AT EQUITABLE FIRE

On Medal Day 1913, a dozen men were to be awarded FDNY medals of valor. Four of those joining the mayor on the steps of City Hall were being honored for their heroism at the Equitable Building fire. Engineer of Steamer Seneca Larke Jr. was awarded the James Gordon Bennett Medal (the department’s oldest and highest award) and $500 in gold from the Bankers Police-Fire Fund. Also awarded medals were Fireman James Brown, Fireman James Molloy and Charles Rankin, who had recently been promoted to lieutenant. A number of other firemen were placed on the Roll of Merit for their bravery that cold January morning.

As a result of the Equitable Building fire and a smoky fire during rush hour in the Broadway subway line where more than 700 people were overcome, the FDNY created a rescue company with the capabilities to cut through iron bars in seconds rather than hours and with smoke helmets that allowed entry into the heaviest smoke and gas situations. After a period of intense training, Rescue Company 1 went into service on March 6, 1915.

—Paul Hashagen

In its day, no other private business building in the world could compare with the Equitable Life Assurance Building in New York City in respect to the magnitude of the monetary...

www.firehouse.com

EQUITABLE BUILDING FIRE

FIRE BUILDING