You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FDNY and NYC Firehouses and Fire Companies - 2nd Section

- Thread starter mack

- Start date

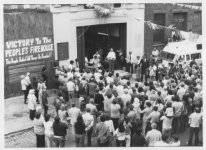

New Yorkers occupy Engine Company 212 (People's Firehouse), 1975-1977

Goals

To make the city government reopen Engine Company 212Time period

November, 1975 to May, 1977Location City/State/Province

Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York City, New YorkIn 1975 and 1976, New York City instituted deep budget cuts that angered the local people and led to many sit-ins and occupations around the city. In the spring of 1975, fears from the recession and government budgets made the banks refuse to market city bonds. Under the urging of the state and national governments to regain access to the bond market, Mayor Abraham D. Bearne proposed austerity budgets that would cut spending on schools, libraries, firehouses, and would charge tuition for the City University of New York for the first time.

Public sector unions organized a mass march on Wall Street to protest the cuts. When the city instituted the cuts in early July, laid-off police, sanitation workers, and others organized various protests across the city.

In November of 1975, the city announced that it would shut down Engine Company 212, a fire station in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The historical fire house on Wythe Avenue was built in 1869 and it was a key fixture in the community.

The neighborhood in North Brooklyn, which was predominantly Polish-American, was already angry with the city government for demolishing houses in order to build more factory space and local people saw the cut as part of the government’s plan to condemn their neighborhood. Williamsburg was suffering from the city policy of “planned shrinkage” where budgets for the police, education, maintenance, and other public services were cut. In many cases, it was more expensive for the city to board up or demolish buildings, so the government often allowed buildings to crumble or burn down. The community faced a high rate of arson, and landlords were known to set buildings on fire in order to receive money from insurance policies because the damaged buildings were not fit for renting out.

To many local residents, the firehouse was an essential public service that protected the neighborhood from problems of neglect and arson that made the other boroughs dangerous. Residents strongly opposed the closing of the fire house because the neighborhood contained many wood-frame buildings and the city was plagued by fires. Old wooden homes were also in close proximity to factories and sites of chemical storage.

Besides the threat of immediate danger, the closing of the firehouse was also seen by New Yorkers as part of the larger failure of government to address the needs of the working-class. Residents came to protest a history of neglect from New York City’s mayoral administration and against the bureaucracy of the city government.

The night before Thanksgiving, the city set the firehouse to close at the end of the day’s shift. One of the firemen opposed to the closing of the station continued to ring the air raid siren to attract people to the firehouse. The local residents flocked to the fire station to protest its closing. By the time city officials came to remove the fire truck from Engine 212, more than 200 protesters had congregated on the street. When firemen inside opened the doors at 6:00 pm, the neighborhood stormed inside the firehouse and prevented the firemen and the engine from leaving the firehouse.

By 9:00pm, the protesters released the firemen, but refused to leave the firehouse or let the fire engines be driven away in order to force the city to listen to their demands. The city ordered police to forcibly remove the protesters, but the Battalion Chief of the 11th division refused, saying “We’re not going to remove them. It’s the people’s firehouse”. The name caught on and the campaign came to be known as the fight to save the “People’s Firehouse”.

Groups of protesters lived in the fire station and organized a system to sleep and eat there. Organizers Adam Venezki, a local grocer and activist, and Jeff Poulaski, an injured factory worker that had been laid off, created shifts for Northsiders to occupy the firehouse for 24 hours every day. Protesters held meetings for the community every Tuesday night and attracted many activists to join and meet there. Protesters vowed to stay at the firehouse until the station reopened.

During the sit-in, supporters including the Boy Scouts, the elderly, and entire families would rotate shifts on the mattresses to block any attempts to remove the protestors from the firehouse. The diversity of support that the campaign received allowed it to prevent opponents from discrediting the protesters’ demands, even though one city official called the campaigners Communists.

After a 16-month occupation, the firehouse was reopened and re-commissioned as “Utility Unit 1”. As a utility unit, the company could only respond to fires in its immediate vicinity but was unable to serve the whole community. The neighborhood would occupy the firehouse again in 1991 for a year to upgrade the utility unit to a fully functional engine company.

The campaign inspired the creation of People’s Firehouse Inc. (PFI), a civilian advocacy group for firefighters. Its mission was to preserve Engine 212 and it worked in affordable housing development, social and legal tenant services, education and vocational training, and energy conservation programs in Williamsburg.

However, the firehouse would finally be closed down in 2003 as a result of another round of budget cuts. There are plans to restore the old firehouse and create North Brooklyn Town Hall and Community and Cultural Center (NTHCCC), a public meeting space, arts and performance venue, and a space for community organizations.

Engine Company 212 - The People's Firehouse

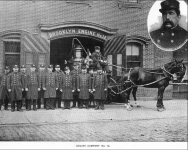

The People's Firehouse F.D.N.Y. Engine Company 212 began as Engine Company 12 of the Brooklyn Fire Department at 136 Wythe Avenue in 186...

Engine 212 LODDs:

FF Charles McHugh, August 8, 1889

Engine 12 was responding to an alarm for fire at 129 Kent Street. FF McHugh was driver of Engine 12's horse-drawn hose tender. The tender wheels struck car tracks in the street and FF McHugh was thrown from his seat on the tender. He died from his injuries.

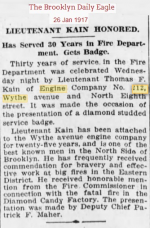

LT Thomas F. Kain, January 12, 1931

LT Thomas F. Kain of Engine 212 was overcome by smoke while operating at a fire at 152 India Street. In his forty-nine years as a fireman this was his first injury. He was taken to St. Catherine's Hospital. Several hours after completing his fiftieth anniversary he passed away. Knowing he was slipping, his only wish was to see his fiftieth anniversary. He was a member of Engine 212 for the past twenty years and was seventy-one years old at his death. He lived in the Howard Beach section of Queens. - From "The Last Alarm" by Boucher, Urbanowicz & Melahn

RIP. Never forget.

FF Charles McHugh, August 8, 1889

Engine 12 was responding to an alarm for fire at 129 Kent Street. FF McHugh was driver of Engine 12's horse-drawn hose tender. The tender wheels struck car tracks in the street and FF McHugh was thrown from his seat on the tender. He died from his injuries.

LT Thomas F. Kain, January 12, 1931

LT Thomas F. Kain of Engine 212 was overcome by smoke while operating at a fire at 152 India Street. In his forty-nine years as a fireman this was his first injury. He was taken to St. Catherine's Hospital. Several hours after completing his fiftieth anniversary he passed away. Knowing he was slipping, his only wish was to see his fiftieth anniversary. He was a member of Engine 212 for the past twenty years and was seventy-one years old at his death. He lived in the Howard Beach section of Queens. - From "The Last Alarm" by Boucher, Urbanowicz & Melahn

RIP. Never forget.

- Joined

- Jan 20, 2014

- Messages

- 19,535

Was this the only patch ever made for this company?