You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FDNY and NYC Firehouses and Fire Companies - 2nd Section

- Thread starter mack

- Start date

FIREHOUSE, ENGINE COMPANY 46 (now Engine Company 46/ Hook & Ladder Company 17), 451-453 East 176th Street, Borough of the Bronx Built: 1894 and 1904; Architect: Napoleon LeBrun & Sons Landmark Site: Borough of the Bronx Tax Map 2909, Lot 40 On December 11, 2012 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of Firehouse, Engine Company 46 (Now Engine Company 46/ Hook & Ladder Company 17) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.1).The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were two speakers in favor of designation including a representative of Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz, Jr. and a representative of the Historic District Council. There were no speakers in opposition. In addition, the Commission has received a letter from the Fire Department of the City of New York in support of designation.

Summary

Fire Engine Company 46 (now Engine Company 46/ Hook & Ladder Company 17) was designed by the prominent architectural firm of Napoleon LeBrun & Sons, architects for the Fire Department between 1879 and 1895. Erected in two campaigns, the first building was completed in 1894 and the second in 1904 as the population and number of buildings expanded in the Bathgate section of the Bronx. The Renaissance Revival style building for Fire Engine Company 46 is an excellent example of LeBrun’s numerous midblock houses for the fire department, reflecting the firm’s careful attention to materials, stylistic detail, plan and setting. LeBrun’s firm helped to define the Fire Department’s expression of civic architecture, both functionally and symbolically, in more than forty buildings it designed during a period of intensive growth in northern Manhattan and the Bronx. This firehouse, with its classical details such as garlanded spandrel panels, dentiled courses, medallions and corbels, represents the city’s commitment to the important civic character of essential municipal services. The design of the original building, with three bays above a large, central vehicular entrance flanked by a smaller window and door, was repeated on the second building ten years later, and the entire composition creates a substantial street presence that continues to suggest the vital role of the Fire Department. Over the years, this building has housed several engine and hook and ladder companies, including Hook & Ladder Company 27 and 58, as well as the offices of the Fire Marshalls and the Bureau of Fire Communications; it currently is the home of Engine Company 46/ Hook & Ladder Company 17

Summary

Fire Engine Company 46 (now Engine Company 46/ Hook & Ladder Company 17) was designed by the prominent architectural firm of Napoleon LeBrun & Sons, architects for the Fire Department between 1879 and 1895. Erected in two campaigns, the first building was completed in 1894 and the second in 1904 as the population and number of buildings expanded in the Bathgate section of the Bronx. The Renaissance Revival style building for Fire Engine Company 46 is an excellent example of LeBrun’s numerous midblock houses for the fire department, reflecting the firm’s careful attention to materials, stylistic detail, plan and setting. LeBrun’s firm helped to define the Fire Department’s expression of civic architecture, both functionally and symbolically, in more than forty buildings it designed during a period of intensive growth in northern Manhattan and the Bronx. This firehouse, with its classical details such as garlanded spandrel panels, dentiled courses, medallions and corbels, represents the city’s commitment to the important civic character of essential municipal services. The design of the original building, with three bays above a large, central vehicular entrance flanked by a smaller window and door, was repeated on the second building ten years later, and the entire composition creates a substantial street presence that continues to suggest the vital role of the Fire Department. Over the years, this building has housed several engine and hook and ladder companies, including Hook & Ladder Company 27 and 58, as well as the offices of the Fire Marshalls and the Bureau of Fire Communications; it currently is the home of Engine Company 46/ Hook & Ladder Company 17

Last edited:

DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS

Firefighting in New York

From the earliest colonial period, the government of New York took the possibility of fire very seriously. Under Dutch rule all men were expected to participate in firefighting activities. After the English took over, the Common Council organized a force of 30 volunteer firefighters in 1737. They operated two Newsham hand pumpers that had recently been imported from London. By 1798, the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), under the supervision of a chief engineer and six subordinates was officially established by an act of the state legislature.

As the city grew, this force was augmented by new volunteer companies. In spite of growing numbers of firefighters and improvements in hoses and water supplies, fire was a significant threat in an increasingly densely built up city. Of particular significance was the “Great Fire” of December 16-17, 1835, which caused more damage to property than any other event in the early years of New York City. The damages resulting from several major fires between 1800 and 1850 led to the establishment of a building code, and an increase in the number of firemen from 600 in 1800 to more than 4,000 in 1865. Despite rapid growth, the department was often criticized for poor performance.3 Intense competition between companies began to hinder firefighting with frequent brawls and acts of sabotage, often at the scenes of fires. During the Civil War, when fire personnel became harder to retain, public support grew for the creation of a professional firefighting force, similar to that which had been established in other cities and to the professional police force that had been created in New York in 1845.

In May 1865, the New York State Legislature established the Metropolitan Fire District, comprising the cities of New York (south of 86th Street) and Brooklyn. The act abolished the volunteer system and created the Metropolitan Fire Department, a paid professional force under the jurisdiction of the state government. By the end of the year, the city’s 124 volunteer companies with more than 4,000 men had retired or disbanded, to be replaced by 33 engine companies and 12 ladder companies operated by a force of 500 men. Immediate improvements included the use of more steam engines, horses and a somewhat reliable telegraph system. A military model was adopted for the firefighters, which involved the use of specialization, discipline, and merit. By 1870, regular service was extended to the “suburban districts” north of 86th Street and expanded still farther north after the annexation of parts of the Bronx in 1874. New techniques and equipment, including taller ladders and stronger steam engines, increased the department’s efficiency, as did the establishment, in 1883, of a training academy for personnel. The growth of the city during this period placed severe demands on the fire department to provide services, and in response the department undertook an ambitious building campaign. The area served by the FDNY nearly doubled after consolidation in 1898, when the departments in Brooklyn and numerous communities in Queens and Staten Island were incorporated into the city. After the turn of the century, the Fire Department acquired more modern apparatus and motorized vehicles, reflecting the need for faster response to fires in taller buildings. Throughout the 20th century, the department has endeavored to keep up with the evolving city and its firefighting needs.

Firehouse Design

Early firehouses often took the form of a simple wooden storage shed, but as the fire department evolved from a volunteer group to a paid professional service, their facilities evolved as well, into more efficient spaces for men and equipment as well as imposing architectural expressions of civic character. As early as 1853, Marriott Field had argued in his City Architecture: Designs for Dwelling Houses, Stores, Hotels, etc. for symbolic architectural expression in municipal buildings, including firehouses. The 1854 Fireman’s Hall, with its highly symbolic ornamentation, reflected this approach, using flambeaux, hooks, ladders, and trumpets for its ornament.

During the second half of the 19th century, architects and builders often drew from various historical prototypes as inspiration for their building designs. Certain types of structures were deemed appropriate for particular contemporary buildings, such as armories based on medieval castles, or school buildings following Gothic or Colonial models. Firehouses, with their unique functions, had no such particular style as a guide, leaving firehouse designers more open to a variety of shapes, designs and styles. In addition, the large population increases of the 1880s and 90s required that more firehouses be built, and larger budgets enabled designers to create more interesting and substantial buildings. A later article in The Brickbuilder summed up the situation,

[The fire station] is exactly the type of building which is extremely interesting to an architect, being devoid of serious difficulties and of a size and character which permit excellent results... and they [firehouses] can be made attractive and express an appreciation of civic care which should be apparent in all city work.

A firehouse had certain simple requirements, such as a large door on the ground story and windows above for the living spaces. Beyond that, architects could experiment somewhat with size and decorative features, giving them some leeway in their designs, for these buildings that were located throughout the city. While the buildings were generally designed to blend in to their neighborhoods, at the same time architects were required to create an appropriately civic statement and a building that was distinct enough that people would instantly understand what it was.

As more firehouses were built and their importance understood, more trained architects were hired for the job. Between 1880 and 1895, Napoleon LeBrun & Son served as the official architectural firm for the fire department, designing 42 fire structures in a massive effort to modernize the facilities and to accommodate the growing population of the city. Although the firm’s earliest designs were relatively simple, later buildings were more distinguished and more clearly identifiable as firehouses.

After LeBrun’s death in 1895, the department commissioned a number of well-known architects to design firehouses. Influenced by the classical revival style that was popular throughout the country, New York firms such as Hoppin & Koen, Flagg & Chambers, and Horgan & Slatterly created facades with bold, classical style designs.

After the turn of the 20th century, the Fire Department also used its own employees to design a series of buildings, all executed in a formal neo-Classical style consistent with the ideas promoted by the City Beautiful movement. Government buildings were placed in neighborhoods throughout the city, with the intention of inspiring civic pride in the work of the government and the country as a whole. Buildings such as these firehouses are easily recognizable and announce themselves as distinct from private structures, using quality materials, workmanship and details to create buildings of lasting beauty and significance to their localities.

Growth of The Bronx and the Bathgate Section

The village of Fordham was the first to develop west of the Bronx River, due to the establishment of St. John’s College (later Fordham University) on the Rose Hill estate and contributed to the need for the Fordham station of the New York and Harlem Railroad, the first one built on the mainland. Numerous mills were also established along the Bronx River, attracting growing numbers of settlers to the area. As the population west of the river grew, the Legislature divided the town of Westchester in 1846, designating the area west of the river as West Farms.

These changes inspired the expansion of large sections of the region into suburban villages. The first town developed by Gouverneur Morris II, with Nicholas McGraw, was called Morrisania, named to honor the old colonial manor that had once stood nearby. In 1850, Morris worked with surveyor Andrew Findley to lay out the villages of Woodstock, Melrose, Melrose East and Melrose South. Jordan Mott purchased 100 acres from Morris to create the town of Mott Haven, adjacent to his J.L. Mott Iron Works factory, while Robert Elton purchased 7 acres that became Eltonia. A 140 acre tract north of Morrisania was purchased in 1841 by Alexander Bathgate, a Scottish immigrant, who had been overseer of the Morris Manorlands. He built his own farmhouse near what is now Third Avenue and East 172nd Street. This property was inherited by his sons, and part of it was sold for building lots beginning in 1851. A section of Bathgate’s property consisted of “the Bathgate Woods,” a large tract of unspoiled land that was home to a large variety of bird species. The forest attracted many hunters, and later (c. 1883) was purchased by the city and renamed Crotona Park. The village of Bathgate developed west of the park and later became part of the Tremont section of The Bronx.

In 1874, the townships of Morrisania, West Farms and Kingsbridge split completely from Westchester County and became the 23rd and 24th wards of the City of New York. This area of the Bronx became known as the Annexed District. Beginning in the early 1880s, booster organizations such as the North Side Association advocated for infrastructure improvements such as street paving and new sewers. The elevated railroad began a line along Third Avenue in 1888, furthering the process of urbanization, which increased more substantially with the arrival of the subway in 1904.

The population of the Bronx grew rapidly. Many of the people who came to live in the Bronx were skilled craftsmen attracted to the new industries being established there. Others were new immigrants, many from Ireland and Germany, countries that were undergoing political upheavals. African-Americans also settled in the new areas, since there was officially no slavery in New York by this time and there are records indicating that some churches and schools were fully integrated. In its early years, the Bathgate section also attracted many Jews who were moving out of Manhattan’s Lower East Side to get more air and space. The various ethnic groups tended to settle together in different sections.

In 1890, there were 89,000 people living in the area of the Bronx known as the North Side; ten years later it had more than doubled to over 200,000. By 1915, this number had increased threefold, to 616,000. As the population and number of new buildings increased, protection from the ever-present danger of fire grew increasingly important. Beginning in the 1880s the Fire Department created many new companies and built many new firehouses so it could expand its efforts in the area to protect the growing numbers of buildings throughout the Annexed District.

Napoleon LeBrun & Sons Napoleon LeBrun (1821-1901) was an architect and engineer who trained under Thomas U. Walter, the designer of the dome and wings of the U.S. Capitol building. LeBrun opened his own office in Philadelphia in 1841 and designed numerous churches in that city, as well as residential and commercial buildings. Moving to New York in 1864, LeBrun also had a successful and varied practice in this city, including a prize-winning design for the Masonic Temple (1870) at Sixth Avenue and 23rd Street. In the 1880s, LeBrun expanded his firm to include his sons, Pierre and Michel and the firm was renamed. Among his best-known skyscrapers in New York are the Home Life Insurance Building (1892-4, 256-7 and 253 Broadway), the Metropolitan Life Insurance Building (1907-09, 1 Madison Avenue), both designated New York City Landmarks.

Between 1880 and 1895, LeBrun’s firm was the official architect for the New York City Fire Department, designing 42 structures throughout Manhattan and the Bronx, in a wide variety of styles, adapting the buildings to fit within their particular neighborhoods. While the basic function and requirements of the firehouse were established early in its history, LeBrun is credited with standardizing the program, and introducing some minor, but important, innovations in the plan. Placing the horse stalls in the main part of the ground floor to reduce the time needed for hitching horses to the apparatus was one such innovation.19

Firehouses were often located on mid-block sites because these were less expensive than more prominent corner sites. Since the sites were narrow, firehouses tended to be three stories tall, with the apparatus on the ground story and rooms for the company, including dormitory, kitchen and captain’s office, above. The other basic design element common to all was a large, central vehicular door, to make it easier for the engines to exit the buildings. Thus the ground story was always symmetrically arranged around this opening, flanked by a smaller pedestrian door and window. Beyond these basic requirements, the architect often applied various styles and details to make the buildings distinctive or to relate the building to its particular neighborhood. LeBrun’s firm often used classically-inspired styles popularized at the time by the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Engine Company 46

Engine Company 46 was originally organized in 1881 in response to the growing population of the area. As a “combination” company, Engine 46 had both a truck and an engine under the command of a single captain. The company was first housed in rental quarters on Morris Street, between Madison and Washington avenues. By 1883, the need for a new house for this company was recognized in the annual report (along with Engine Companies 9 and 23). However, it was also noted that the Fire Department was “morally if not legally obligated to continue the lease with the owner of the building now occupied by that company until December 31, 1888, and it was therefore considered proper to defer the erection of a new house.” The company remained at this location until 1893 when two lots were purchased on East 176th Street, 150 feet west of Washington Avenue. In 1894, the building for Engine Company 46 was constructed at 451 East 176th Street, designed by the firm of Napoleon LeBrun & Sons. The second building (on the second lot) was constructed in 1903-04, for Hook & Ladder Company 27, and was also designed by LeBrun’s firm. A second ladder company, Hook & Ladder Company 58, was organized at this same location in 1968, to supplement the work of 6 Hook & Ladder Company 27 because of the numerous calls to which these companies responded during this period.

These companies continued to operate out of these buildings until 1972 when Engine Company 46 and Hook & Ladder Company 27 moved to new quarters at 460 Cross Bronx Expressway. At this time the Bureau of Fire Investigation (Fire Marshalls) and the Bureau of Fire Communications took up residence in these buildings on East 176th Street. (Hook & Ladder Company 58 remained at this location until 1974.) In 1992, these services were relocated again and the two buildings were occupied by Rescue Company 3, which previously had been located on West 181st Street. Today these buildings are again occupied by an engine company and a ladder company.

This building was one of many designed by LeBrun’s firm throughout Manhattan and the Bronx. With so many buildings being produced over a short time, it was not uncommon for similar buildings to be built in different parts of the city. The firehouse at 530 West 43rd Street in Manhattan (demolished) was very similar to this one in the Bronx and was built immediately following it.

Description

This three-story, six-bay wide building occupies a mid-block site. The eastern side is not visible due to the adjacent building and the plain brick western side is visible only above the adjacent one-story building. The ground story is faced with brownstone and the two upper floors are faced with light brick with banding. The facade consists of two, almost identical, 3-bay sections.

Historic:

Ground story: each section has large, central vehicular entrance, with ornamented iron beam across top; iron reveal on vehicle entrance of eastern section; to west of each vehicle entrance is small window with metal grille, to east, pedestrian door, each topped by separate stone transom; stone water table, projecting stone course at sill level; carved stone panel with “46 Engine 46” over western vehicle entrance; panels of terra-cotta ornament over windows and doors of ground story; dentil course between ground story from second story. Upper floors: each section has three rectangular windows with original 1/1, wood-sash windows; continuous brownstone sills; separate, brick, flat-arch lintels with embellished, scroll-shaped keystones over each window; lintels on windows of eastern section also topped by moldings; round terra-cotta medallions and bronze plaque between second and third story windows; terra-cotta frieze with framed panels under terra-cotta cornice supported on embellished scroll brackets.

Alterations:

Vehicular doors replaced; pedestrian doors replaced; transoms filled by painted panels; several lights, intercoms, alarms added; sign added over eastern vehicle entrance; flag pole projects from second story. Report researched and written by Virginia Kurshan Research Department

Report researched and written by Virginia Kurshan Research Department

Firefighting in New York

From the earliest colonial period, the government of New York took the possibility of fire very seriously. Under Dutch rule all men were expected to participate in firefighting activities. After the English took over, the Common Council organized a force of 30 volunteer firefighters in 1737. They operated two Newsham hand pumpers that had recently been imported from London. By 1798, the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), under the supervision of a chief engineer and six subordinates was officially established by an act of the state legislature.

As the city grew, this force was augmented by new volunteer companies. In spite of growing numbers of firefighters and improvements in hoses and water supplies, fire was a significant threat in an increasingly densely built up city. Of particular significance was the “Great Fire” of December 16-17, 1835, which caused more damage to property than any other event in the early years of New York City. The damages resulting from several major fires between 1800 and 1850 led to the establishment of a building code, and an increase in the number of firemen from 600 in 1800 to more than 4,000 in 1865. Despite rapid growth, the department was often criticized for poor performance.3 Intense competition between companies began to hinder firefighting with frequent brawls and acts of sabotage, often at the scenes of fires. During the Civil War, when fire personnel became harder to retain, public support grew for the creation of a professional firefighting force, similar to that which had been established in other cities and to the professional police force that had been created in New York in 1845.

In May 1865, the New York State Legislature established the Metropolitan Fire District, comprising the cities of New York (south of 86th Street) and Brooklyn. The act abolished the volunteer system and created the Metropolitan Fire Department, a paid professional force under the jurisdiction of the state government. By the end of the year, the city’s 124 volunteer companies with more than 4,000 men had retired or disbanded, to be replaced by 33 engine companies and 12 ladder companies operated by a force of 500 men. Immediate improvements included the use of more steam engines, horses and a somewhat reliable telegraph system. A military model was adopted for the firefighters, which involved the use of specialization, discipline, and merit. By 1870, regular service was extended to the “suburban districts” north of 86th Street and expanded still farther north after the annexation of parts of the Bronx in 1874. New techniques and equipment, including taller ladders and stronger steam engines, increased the department’s efficiency, as did the establishment, in 1883, of a training academy for personnel. The growth of the city during this period placed severe demands on the fire department to provide services, and in response the department undertook an ambitious building campaign. The area served by the FDNY nearly doubled after consolidation in 1898, when the departments in Brooklyn and numerous communities in Queens and Staten Island were incorporated into the city. After the turn of the century, the Fire Department acquired more modern apparatus and motorized vehicles, reflecting the need for faster response to fires in taller buildings. Throughout the 20th century, the department has endeavored to keep up with the evolving city and its firefighting needs.

Firehouse Design

Early firehouses often took the form of a simple wooden storage shed, but as the fire department evolved from a volunteer group to a paid professional service, their facilities evolved as well, into more efficient spaces for men and equipment as well as imposing architectural expressions of civic character. As early as 1853, Marriott Field had argued in his City Architecture: Designs for Dwelling Houses, Stores, Hotels, etc. for symbolic architectural expression in municipal buildings, including firehouses. The 1854 Fireman’s Hall, with its highly symbolic ornamentation, reflected this approach, using flambeaux, hooks, ladders, and trumpets for its ornament.

During the second half of the 19th century, architects and builders often drew from various historical prototypes as inspiration for their building designs. Certain types of structures were deemed appropriate for particular contemporary buildings, such as armories based on medieval castles, or school buildings following Gothic or Colonial models. Firehouses, with their unique functions, had no such particular style as a guide, leaving firehouse designers more open to a variety of shapes, designs and styles. In addition, the large population increases of the 1880s and 90s required that more firehouses be built, and larger budgets enabled designers to create more interesting and substantial buildings. A later article in The Brickbuilder summed up the situation,

[The fire station] is exactly the type of building which is extremely interesting to an architect, being devoid of serious difficulties and of a size and character which permit excellent results... and they [firehouses] can be made attractive and express an appreciation of civic care which should be apparent in all city work.

A firehouse had certain simple requirements, such as a large door on the ground story and windows above for the living spaces. Beyond that, architects could experiment somewhat with size and decorative features, giving them some leeway in their designs, for these buildings that were located throughout the city. While the buildings were generally designed to blend in to their neighborhoods, at the same time architects were required to create an appropriately civic statement and a building that was distinct enough that people would instantly understand what it was.

As more firehouses were built and their importance understood, more trained architects were hired for the job. Between 1880 and 1895, Napoleon LeBrun & Son served as the official architectural firm for the fire department, designing 42 fire structures in a massive effort to modernize the facilities and to accommodate the growing population of the city. Although the firm’s earliest designs were relatively simple, later buildings were more distinguished and more clearly identifiable as firehouses.

After LeBrun’s death in 1895, the department commissioned a number of well-known architects to design firehouses. Influenced by the classical revival style that was popular throughout the country, New York firms such as Hoppin & Koen, Flagg & Chambers, and Horgan & Slatterly created facades with bold, classical style designs.

After the turn of the 20th century, the Fire Department also used its own employees to design a series of buildings, all executed in a formal neo-Classical style consistent with the ideas promoted by the City Beautiful movement. Government buildings were placed in neighborhoods throughout the city, with the intention of inspiring civic pride in the work of the government and the country as a whole. Buildings such as these firehouses are easily recognizable and announce themselves as distinct from private structures, using quality materials, workmanship and details to create buildings of lasting beauty and significance to their localities.

Growth of The Bronx and the Bathgate Section

The village of Fordham was the first to develop west of the Bronx River, due to the establishment of St. John’s College (later Fordham University) on the Rose Hill estate and contributed to the need for the Fordham station of the New York and Harlem Railroad, the first one built on the mainland. Numerous mills were also established along the Bronx River, attracting growing numbers of settlers to the area. As the population west of the river grew, the Legislature divided the town of Westchester in 1846, designating the area west of the river as West Farms.

These changes inspired the expansion of large sections of the region into suburban villages. The first town developed by Gouverneur Morris II, with Nicholas McGraw, was called Morrisania, named to honor the old colonial manor that had once stood nearby. In 1850, Morris worked with surveyor Andrew Findley to lay out the villages of Woodstock, Melrose, Melrose East and Melrose South. Jordan Mott purchased 100 acres from Morris to create the town of Mott Haven, adjacent to his J.L. Mott Iron Works factory, while Robert Elton purchased 7 acres that became Eltonia. A 140 acre tract north of Morrisania was purchased in 1841 by Alexander Bathgate, a Scottish immigrant, who had been overseer of the Morris Manorlands. He built his own farmhouse near what is now Third Avenue and East 172nd Street. This property was inherited by his sons, and part of it was sold for building lots beginning in 1851. A section of Bathgate’s property consisted of “the Bathgate Woods,” a large tract of unspoiled land that was home to a large variety of bird species. The forest attracted many hunters, and later (c. 1883) was purchased by the city and renamed Crotona Park. The village of Bathgate developed west of the park and later became part of the Tremont section of The Bronx.

In 1874, the townships of Morrisania, West Farms and Kingsbridge split completely from Westchester County and became the 23rd and 24th wards of the City of New York. This area of the Bronx became known as the Annexed District. Beginning in the early 1880s, booster organizations such as the North Side Association advocated for infrastructure improvements such as street paving and new sewers. The elevated railroad began a line along Third Avenue in 1888, furthering the process of urbanization, which increased more substantially with the arrival of the subway in 1904.

The population of the Bronx grew rapidly. Many of the people who came to live in the Bronx were skilled craftsmen attracted to the new industries being established there. Others were new immigrants, many from Ireland and Germany, countries that were undergoing political upheavals. African-Americans also settled in the new areas, since there was officially no slavery in New York by this time and there are records indicating that some churches and schools were fully integrated. In its early years, the Bathgate section also attracted many Jews who were moving out of Manhattan’s Lower East Side to get more air and space. The various ethnic groups tended to settle together in different sections.

In 1890, there were 89,000 people living in the area of the Bronx known as the North Side; ten years later it had more than doubled to over 200,000. By 1915, this number had increased threefold, to 616,000. As the population and number of new buildings increased, protection from the ever-present danger of fire grew increasingly important. Beginning in the 1880s the Fire Department created many new companies and built many new firehouses so it could expand its efforts in the area to protect the growing numbers of buildings throughout the Annexed District.

Napoleon LeBrun & Sons Napoleon LeBrun (1821-1901) was an architect and engineer who trained under Thomas U. Walter, the designer of the dome and wings of the U.S. Capitol building. LeBrun opened his own office in Philadelphia in 1841 and designed numerous churches in that city, as well as residential and commercial buildings. Moving to New York in 1864, LeBrun also had a successful and varied practice in this city, including a prize-winning design for the Masonic Temple (1870) at Sixth Avenue and 23rd Street. In the 1880s, LeBrun expanded his firm to include his sons, Pierre and Michel and the firm was renamed. Among his best-known skyscrapers in New York are the Home Life Insurance Building (1892-4, 256-7 and 253 Broadway), the Metropolitan Life Insurance Building (1907-09, 1 Madison Avenue), both designated New York City Landmarks.

Between 1880 and 1895, LeBrun’s firm was the official architect for the New York City Fire Department, designing 42 structures throughout Manhattan and the Bronx, in a wide variety of styles, adapting the buildings to fit within their particular neighborhoods. While the basic function and requirements of the firehouse were established early in its history, LeBrun is credited with standardizing the program, and introducing some minor, but important, innovations in the plan. Placing the horse stalls in the main part of the ground floor to reduce the time needed for hitching horses to the apparatus was one such innovation.19

Firehouses were often located on mid-block sites because these were less expensive than more prominent corner sites. Since the sites were narrow, firehouses tended to be three stories tall, with the apparatus on the ground story and rooms for the company, including dormitory, kitchen and captain’s office, above. The other basic design element common to all was a large, central vehicular door, to make it easier for the engines to exit the buildings. Thus the ground story was always symmetrically arranged around this opening, flanked by a smaller pedestrian door and window. Beyond these basic requirements, the architect often applied various styles and details to make the buildings distinctive or to relate the building to its particular neighborhood. LeBrun’s firm often used classically-inspired styles popularized at the time by the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Engine Company 46

Engine Company 46 was originally organized in 1881 in response to the growing population of the area. As a “combination” company, Engine 46 had both a truck and an engine under the command of a single captain. The company was first housed in rental quarters on Morris Street, between Madison and Washington avenues. By 1883, the need for a new house for this company was recognized in the annual report (along with Engine Companies 9 and 23). However, it was also noted that the Fire Department was “morally if not legally obligated to continue the lease with the owner of the building now occupied by that company until December 31, 1888, and it was therefore considered proper to defer the erection of a new house.” The company remained at this location until 1893 when two lots were purchased on East 176th Street, 150 feet west of Washington Avenue. In 1894, the building for Engine Company 46 was constructed at 451 East 176th Street, designed by the firm of Napoleon LeBrun & Sons. The second building (on the second lot) was constructed in 1903-04, for Hook & Ladder Company 27, and was also designed by LeBrun’s firm. A second ladder company, Hook & Ladder Company 58, was organized at this same location in 1968, to supplement the work of 6 Hook & Ladder Company 27 because of the numerous calls to which these companies responded during this period.

These companies continued to operate out of these buildings until 1972 when Engine Company 46 and Hook & Ladder Company 27 moved to new quarters at 460 Cross Bronx Expressway. At this time the Bureau of Fire Investigation (Fire Marshalls) and the Bureau of Fire Communications took up residence in these buildings on East 176th Street. (Hook & Ladder Company 58 remained at this location until 1974.) In 1992, these services were relocated again and the two buildings were occupied by Rescue Company 3, which previously had been located on West 181st Street. Today these buildings are again occupied by an engine company and a ladder company.

This building was one of many designed by LeBrun’s firm throughout Manhattan and the Bronx. With so many buildings being produced over a short time, it was not uncommon for similar buildings to be built in different parts of the city. The firehouse at 530 West 43rd Street in Manhattan (demolished) was very similar to this one in the Bronx and was built immediately following it.

Description

This three-story, six-bay wide building occupies a mid-block site. The eastern side is not visible due to the adjacent building and the plain brick western side is visible only above the adjacent one-story building. The ground story is faced with brownstone and the two upper floors are faced with light brick with banding. The facade consists of two, almost identical, 3-bay sections.

Historic:

Ground story: each section has large, central vehicular entrance, with ornamented iron beam across top; iron reveal on vehicle entrance of eastern section; to west of each vehicle entrance is small window with metal grille, to east, pedestrian door, each topped by separate stone transom; stone water table, projecting stone course at sill level; carved stone panel with “46 Engine 46” over western vehicle entrance; panels of terra-cotta ornament over windows and doors of ground story; dentil course between ground story from second story. Upper floors: each section has three rectangular windows with original 1/1, wood-sash windows; continuous brownstone sills; separate, brick, flat-arch lintels with embellished, scroll-shaped keystones over each window; lintels on windows of eastern section also topped by moldings; round terra-cotta medallions and bronze plaque between second and third story windows; terra-cotta frieze with framed panels under terra-cotta cornice supported on embellished scroll brackets.

Alterations:

Vehicular doors replaced; pedestrian doors replaced; transoms filled by painted panels; several lights, intercoms, alarms added; sign added over eastern vehicle entrance; flag pole projects from second story. Report researched and written by Virginia Kurshan Research Department

Report researched and written by Virginia Kurshan Research Department

According to a retired member, the middle animal on the Harlem Zoo patch represented Squad 1. And more clearly, the animal with the red helmet represented 30 truck and the far right animal represented 59 engine.The FH also in the early '70s also housed the original SQ*1 after they moved from ENG*59 & until SQ*1 moved to ENG*45.

Attachments

A retired member...According to a retired member, the middle animal on the Harlem Zoo patch represented Squad 1. And more clearly, the animal with the red helmet represented 30 truck and the far right animal represented 59 engine.

Not famous, famous more like MSU famousThe zoo patch is no longer authorized for official use.

He’s famous

He’s famous.A retired member...

You stop itNot famous, famous more like MSU famous

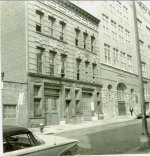

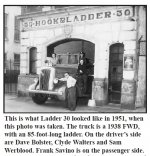

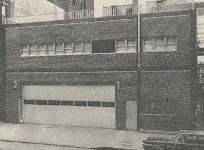

Engine 59/Ladder 30 firehouse 111 W. 133rd Street Harlem, Manhattan Division 6, Battalion 16 "The Harlem Zoo"

Engine 59 organized 180 W. 137th Street 1894

Engine 59 new firehouse 111 W. 133rd Street w/ Ladder 30 1962

Ladder 30 organized 104 W. 135th Street 1907

Ladder 30 new firehouse 111 W. 133rd Street w/Engine 59 1962

Squad 1 organized 180 W. 137th Street at Engine 59 1955

Squad 1 new firehouse 111 W. 133rd Street at Engine 59 1962

Squad 1 moved 451 E. 176th Street at Ladder 58 1972

Squad 1 moved 925 E. Tremont Street at Engine 45 1975

Squad 1 disbanded 1976

Ambulance 1 located 111 W. 133rd Street at Engine 59 1972-1987

Engine 59 organized 180 W. 137th Street 1894

Engine 59 new firehouse 111 W. 133rd Street w/ Ladder 30 1962

Ladder 30 organized 104 W. 135th Street 1907

Ladder 30 new firehouse 111 W. 133rd Street w/Engine 59 1962

Squad 1 organized 180 W. 137th Street at Engine 59 1955

Squad 1 new firehouse 111 W. 133rd Street at Engine 59 1962

Squad 1 moved 451 E. 176th Street at Ladder 58 1972

Squad 1 moved 925 E. Tremont Street at Engine 45 1975

Squad 1 disbanded 1976

Ambulance 1 located 111 W. 133rd Street at Engine 59 1972-1987

Last edited:

Maybe middle animal represented Ambulance 1. It has a 1st aid bag.According to a retired member, the middle animal on the Harlem Zoo patch represented Squad 1. And more clearly, the animal with the red helmet represented 30 truck and the far right animal represented 59 engine.

Ambulance 1 was located with E 59/L 30 from 1972-1987.

Squad 1 was located at E 59 at 1380 W 137th St 1955-1962 then at E 59/L30's new quarters at 111 W 133rd Street from 1962-1972.

More E 59/L 30/S 1/Amb 1 history at:

nycfire.net

nycfire.net

FDNY and NYC Firehouses and Fire Companies - 2nd Section

Engine 282: FIREFIGHTER JAMES A. DINGEE ENGINE 282 August 23, 1943 James Dingee, Engine 282, enlisted in the US Navy during World War II. His armed service number was 8087463. He was killed in action as a firefighter in combat when his ship was attacked by enemy aircraft. FF...

nycfire.net

nycfire.net

Note - The pastor of my church had a Ladder 30 helmet hung in the lobby for many years. It was his father's, FF John Steakem, Ladder 30. FF Steakem was awarded a medal in 1931 and then was an LODD in 1940 when he died following an apartment fire. The priest told me how difficult the loss of his father was for family with young children and that his mom could not afford to get by on the limited death benefits. They had to move from NYC to RI and live with her sister where he grew up and then became a priest - always proud of his FDNY father and hero. RIP.

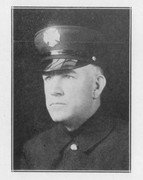

JAMES J. STEAKEM FF. LAD. 30 APR. 10, 1930 1931 PRENTICE MEDAL

FIREFIGHTER JAMES J. STEAKEM LADDER 30 May 15, 1940 LODD

Fireman James J. Steakem reported to the quarters of Ladder 30 at 4:00 p.m. for his regularly scheduled tour of duty. Ladder 30 responded to 2182 Lexington Avenue for a small fire at 5:28 p.m. The company returned to quarters at 5:40. At 6:45 Fireman Steakem reported to the company officer that he was suffering severe chest and stomach pains. An ambulance was called and Fireman Steakem was transported to Knickerbocker Hospital at 70 Convent Avenue. Doctors thought that he was suffering from a ruptured gastric ulcer, but at 2:10 a.m. on May 15 he died of a heart attack. Fireman Steakem was appointed to the Department on February 1, 1920 at the age of 33 and was married. He spent all of his time in the Fire Department in Ladder 30. (From "The Last Alarm)

JAMES J. STEAKEM FF. LAD. 30 APR. 10, 1930 1931 PRENTICE MEDAL

FIREFIGHTER JAMES J. STEAKEM LADDER 30 May 15, 1940 LODD

Fireman James J. Steakem reported to the quarters of Ladder 30 at 4:00 p.m. for his regularly scheduled tour of duty. Ladder 30 responded to 2182 Lexington Avenue for a small fire at 5:28 p.m. The company returned to quarters at 5:40. At 6:45 Fireman Steakem reported to the company officer that he was suffering severe chest and stomach pains. An ambulance was called and Fireman Steakem was transported to Knickerbocker Hospital at 70 Convent Avenue. Doctors thought that he was suffering from a ruptured gastric ulcer, but at 2:10 a.m. on May 15 he died of a heart attack. Fireman Steakem was appointed to the Department on February 1, 1920 at the age of 33 and was married. He spent all of his time in the Fire Department in Ladder 30. (From "The Last Alarm)