You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FDNY and NYC Firehouses and Fire Companies - 2nd Section

- Thread starter mack

- Start date

Engine 78 (Marine) Manhattan BECAME MARINE 5

Engine 78 organized foot of foot of Gansevoort Street North River 1904

Engine 78 moved foot of E 99th Street Harlem River 1908

Engine 78 new quarters foot of E 90th Street Harlem River 1930

Engine 78 disbanded to form Marine 5 1959

Engine 78 quarters E 90th Street Harlem River:

Engine 78 "George B. McClellan":

1904-1938

117' x 24' x 9'6"

7000 GPM

Built by New York Shipping Company, Camden, NJ

Steel hull

Coal fired

3 deck pipes

16 discharges

Engine 78 "George B. McClellan" members:

Engine 78 "Thomas Willett":

1938-1959

132' x 28' x 10'

9000 GPM

Built by Alexander Miller & Brothers, Jersey City, NJ

Coal fire steam turbine driven centrifugal pumps

4 deck pipes

Tower mast

14 knots

Converted from coal to oil in 1926

Engine 78 Medals:

JOHN B. CONLON CAPT. ENG. 78 1904 1905 STEPHENSON

Captain - best administrative and disciplined company.

FRANK HAUNFELDER LT ENG. 78 APR. 24, 1943 1944 CONRAN

Heroism while fighting fire on World War II munitions ship SS El Estero that caught fire at dockside in Jersey City April 24, 1943

JOHN K. MC CULLOCH FF. ENG. 78 E-57 OCT. 31, 1951 1952 CRIMMINS

URBAN C. J. HIGGINS LT. ENG. 78 MAR. 14, 1953 1954 SCOTT

Engine 78 organized foot of foot of Gansevoort Street North River 1904

Engine 78 moved foot of E 99th Street Harlem River 1908

Engine 78 new quarters foot of E 90th Street Harlem River 1930

Engine 78 disbanded to form Marine 5 1959

Engine 78 quarters E 90th Street Harlem River:

Engine 78 "George B. McClellan":

1904-1938

117' x 24' x 9'6"

7000 GPM

Built by New York Shipping Company, Camden, NJ

Steel hull

Coal fired

3 deck pipes

16 discharges

Engine 78 "George B. McClellan" members:

Engine 78 "Thomas Willett":

1938-1959

132' x 28' x 10'

9000 GPM

Built by Alexander Miller & Brothers, Jersey City, NJ

Coal fire steam turbine driven centrifugal pumps

4 deck pipes

Tower mast

14 knots

Converted from coal to oil in 1926

Engine 78 Medals:

JOHN B. CONLON CAPT. ENG. 78 1904 1905 STEPHENSON

Captain - best administrative and disciplined company.

FRANK HAUNFELDER LT ENG. 78 APR. 24, 1943 1944 CONRAN

Heroism while fighting fire on World War II munitions ship SS El Estero that caught fire at dockside in Jersey City April 24, 1943

JOHN K. MC CULLOCH FF. ENG. 78 E-57 OCT. 31, 1951 1952 CRIMMINS

URBAN C. J. HIGGINS LT. ENG. 78 MAR. 14, 1953 1954 SCOTT

Engine 57 (Marine) Manhattan BECAME MARINE 1

Engine 57 organized Castle Garden 1891

Engine 57 new quarters Battery Park 1895

Engine 57 moved Pier 1, Hudson River 1941

Engine 57 disbanded to form Marine 1 1959

Engine 52 locations:

Castle Garden, Battery 1891-1895:

New York City immigrant processing center 1855-1890. New York City Aquarium 1896-1941.

Battery Park 1894-1941:

Pier 1 Hudson River 1941-1959:

Engine 57 fireboats:

"The New Yorker"

1891 to 1922

125' x 26' x 12'

13,000 GPM

Steel hull

Coal fired

Steam power

Engine 57 organized Castle Garden 1891

Engine 57 new quarters Battery Park 1895

Engine 57 moved Pier 1, Hudson River 1941

Engine 57 disbanded to form Marine 1 1959

Engine 52 locations:

Castle Garden, Battery 1891-1895:

New York City immigrant processing center 1855-1890. New York City Aquarium 1896-1941.

Battery Park 1894-1941:

Pier 1 Hudson River 1941-1959:

Engine 57 fireboats:

"The New Yorker"

1891 to 1922

125' x 26' x 12'

13,000 GPM

Steel hull

Coal fired

Steam power

Engine 57 (Marine) continued:

"John J. Harvey"

1931-1938

130' x 28' x 9'

18,000 GPM

Built by Todd Shipyards, Brooklyn, NY.

First gasoline-electric powered fireboat

5 gasoline motors

4 fire pumps

Twin screws

8 deck pipes

Proud History

In the 1920's the New York City Fire Department's fleet of 10 steam fireboats was aging, and it was decided to construct a new fireboat with internal combustion power. Basic plans were prepared in 1928. Contracts were drawn up and construction started in 1930 by Todd Shipbuilding's Plant at the foot of 23rd Street on Brooklyn's Gowanus Bay. Launching took place on October 6, 1931 with the boat completed and placed in commission on December 17, 1931.

Harvey's dimensions are 130' long with a 28' beam and a 9' draft. She is of steel construction with a riveted hull. Propulsion is by twin screws six feet in diameter.

She was the largest, and most powerful fireboat in the world when built. More importantly, she was the model of modern fireboat engineering, and set the pattern for all subsequent fireboats to follow.

(from FIREBOAT.ORG https://www.1931fireboat.org/index.php)

"Fire Fighter"

1938-1955

134' x 32' x 9'

20,000 GPM

Designed by Gibbs & Cox

Built by United Shipyards of Staten Island

First Diesel-electric fireboat

8 deck monitors

55 foot water tower

http://www.americasfireboat.org/1938-1955-engine-57-marine-unit-1-battery-manhattan/

"John D. McKean"

1954-1959

129' x 30' x 9'

19,000 GPM

Built by John Mathis Shipyard in Camden, NJ

6 monitors

Water tower mast

http://marine1fdny.com/mckean_new.php

Engine 57 history:

1891 Fireboat New Yorker, as Engine 57 placed in service at Battery Park seawall. She is the most powerful fireboat ever built with a capacity of 13,000 gpm, and would remain the flagship of the fleet for many years. This company could be considered the ancestor of Marine Co. 1, and a fireboat would be stationed near The Battery for over 100 years.

1895 An ornate Victorian two story house is constructed along the Battery Park seawall for Engine 57. From now on fireboats would have permanent shoreside quarters.

1898 Consolidation of the City of New York, adds greatly to the City limits. The City of Brooklyn is included, which has a Fire Department almost as large as New York's and an equally important waterfront. The Brooklyn Fire Department, along with its own two fireboats, is now absorbed into the New York Fire Department.

1908 Three fireboats are added to the FDNY fleet, bringing the size of the fleet to 10 large fireboats. From this point on, the Engine Company numbers would be associated with a particular berth, not necessarily the boat assigned to it. With this increase the fireboats are now organized as the Marine Division.

1922 The new steam fireboat, John Purroy Mitchel is assigned to Engine 57. She was the last steam fireboat and the only one built to burn oil; all previous fireboats used coal as fuel, with some later converted to oil-burning. The New Yorker is reassigned to Engine 77 at the foot of Beekman Street, East River.

1931 The new gasoline-electric fireboat, John J. Harvey is assigned to Engine 57 continuing a practice of assigning the most innovative boat to Engine 57. Mitchel is reassigned to Engine 232 at the foot of Noble Street, Greenpoint.

1938 The new diesel-electric Fire Fighter is assigned to Engine 57. The most powerful boat ever in our fleet, she has a capacity of 20,000 gpm. Harvey is reassigned to Engine 86, Pier 53, North River, at the foot of Bloomfield Street.

1941 Due to planned construction of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and Battery Park underpass, reconstruction of the park is started. Plans call for the demolition of the fireboat station. Engine 57 is moved a short distance to "temporary quarters" on North River Pier 1.

1955 The new diesel-electric fireboat John D. McKean is assigned to Engine 57.

1959 Fireboats are changed from their previous Engine Company designations and are now known as Marine Companies. Engine 57 is designated Marine Co. 1.

Engine 57 medals:

THOMAS MALAVEY FF. ENG. 57 JAN. 29, 1900 1902 STRONG

JOHN A. SHEARER PILOT ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 PRENTICE

SVEN VICTOR HULL FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

ALBERT B. HOUSE, JR. FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

PETER A. MC NULTY FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

JOSEPH F. EARNEY FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

SAMUEL BRAISIN PROBIE ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

THOMAS J. WHITE ENGINEER ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 SCOTT

HARRY M. BIFFAR FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

OTTO R. KUTZKE ENGINEER ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 JOHNSTON

Last FDNY member to hold the rank of Engineer of Steamer. Promoted off 1921 list. 45 years of service.

LAWRENCE S. GILLIAM ENGINEER ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 BROOKMAN

Members of Engine 57 were awarded department medals for their heroism averting disaster on April 24, 1943 fighting a fire on the SS El Estero, a ship filled with ammunition.

The El Estero had taken on 1,365 tons of mixed munitions and was preparing to depart at approximately 5:30PM when a boiler flashback started a fire on oily water in her bilges which quickly grew out of control.

The initial report of fire aboard El Estero brought an immediate response of five fire trucks from the Jersey City Fire Department, two 30-foot fireboats and roughly 60 volunteers from the U.S. Coast Guard to battle and contain the flames aboard the ship, which was moored directly opposite two other fully loaded ammunition ships and two ammunition-laden consists of railroad boxcars. With over 5,000 tons of ammunition (comparable to a tactical nuclear weapon now in immediate danger of being set off by the fire on El Estero and with memories of the Black Tom explosion fresh on the minds of many at the scene, fire fighting efforts began in earnest. It was quickly discovered that the location and intensity of the fire prevented access to the ships' seacocks, making any attempt at scuttling the ship impossible, and the call went out to the New York City Fire Department, which in turn dispatched its two most powerful fireboats; Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey, to the scene.

Arriving at 6:30 pm and immediately running hoses up to Coast Guardsmen on the burning ship, the fireboats took positions directly alongside El Estero as a trio of commercial tugboats made up a towline to her bow and began pulling her off the Caven Point Pier towards open waters on through The Narrows. Despite the high probability of the ship's volatile cargo exploding at any moment, the Coast Guardsmen, fire fighters and tug crews continued their efforts to contain the fire on El Estero to save as much of the ship and cargo as possible, but shortly after the tow began the Port Admiral of New York Harbor ordered the ship sunk. Shifting to a shallow area of water near Robbins Reef Light in Upper New York Bay, the fireboats began pumping their combined maximum capacity of 38,000 gallons of water per minute into El Estero's cargo holds, which succeeded in swamping the ship and sent her to the bottom shortly after 9PM with much of her superstructure still above the surface. With all hotspots declared extinguished by 11:30PM on the 24th, the all-clear for residents and businesses ringing New York Harbor was transmitted over the radio and what is considered to have been the single greatest threat to New York City during World War II passed without major incident or loss of life.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_El_Estero

http://www.capecodfd.com/pages%20special/Fireboats_FDNY_H1_Hist-Overview.htm

http://marine1fdny.com/history_new.php

"John J. Harvey"

1931-1938

130' x 28' x 9'

18,000 GPM

Built by Todd Shipyards, Brooklyn, NY.

First gasoline-electric powered fireboat

5 gasoline motors

4 fire pumps

Twin screws

8 deck pipes

Proud History

In the 1920's the New York City Fire Department's fleet of 10 steam fireboats was aging, and it was decided to construct a new fireboat with internal combustion power. Basic plans were prepared in 1928. Contracts were drawn up and construction started in 1930 by Todd Shipbuilding's Plant at the foot of 23rd Street on Brooklyn's Gowanus Bay. Launching took place on October 6, 1931 with the boat completed and placed in commission on December 17, 1931.

Harvey's dimensions are 130' long with a 28' beam and a 9' draft. She is of steel construction with a riveted hull. Propulsion is by twin screws six feet in diameter.

She was the largest, and most powerful fireboat in the world when built. More importantly, she was the model of modern fireboat engineering, and set the pattern for all subsequent fireboats to follow.

(from FIREBOAT.ORG https://www.1931fireboat.org/index.php)

"Fire Fighter"

1938-1955

134' x 32' x 9'

20,000 GPM

Designed by Gibbs & Cox

Built by United Shipyards of Staten Island

First Diesel-electric fireboat

8 deck monitors

55 foot water tower

http://www.americasfireboat.org/1938-1955-engine-57-marine-unit-1-battery-manhattan/

"John D. McKean"

1954-1959

129' x 30' x 9'

19,000 GPM

Built by John Mathis Shipyard in Camden, NJ

6 monitors

Water tower mast

http://marine1fdny.com/mckean_new.php

Engine 57 history:

1891 Fireboat New Yorker, as Engine 57 placed in service at Battery Park seawall. She is the most powerful fireboat ever built with a capacity of 13,000 gpm, and would remain the flagship of the fleet for many years. This company could be considered the ancestor of Marine Co. 1, and a fireboat would be stationed near The Battery for over 100 years.

1895 An ornate Victorian two story house is constructed along the Battery Park seawall for Engine 57. From now on fireboats would have permanent shoreside quarters.

1898 Consolidation of the City of New York, adds greatly to the City limits. The City of Brooklyn is included, which has a Fire Department almost as large as New York's and an equally important waterfront. The Brooklyn Fire Department, along with its own two fireboats, is now absorbed into the New York Fire Department.

1908 Three fireboats are added to the FDNY fleet, bringing the size of the fleet to 10 large fireboats. From this point on, the Engine Company numbers would be associated with a particular berth, not necessarily the boat assigned to it. With this increase the fireboats are now organized as the Marine Division.

1922 The new steam fireboat, John Purroy Mitchel is assigned to Engine 57. She was the last steam fireboat and the only one built to burn oil; all previous fireboats used coal as fuel, with some later converted to oil-burning. The New Yorker is reassigned to Engine 77 at the foot of Beekman Street, East River.

1931 The new gasoline-electric fireboat, John J. Harvey is assigned to Engine 57 continuing a practice of assigning the most innovative boat to Engine 57. Mitchel is reassigned to Engine 232 at the foot of Noble Street, Greenpoint.

1938 The new diesel-electric Fire Fighter is assigned to Engine 57. The most powerful boat ever in our fleet, she has a capacity of 20,000 gpm. Harvey is reassigned to Engine 86, Pier 53, North River, at the foot of Bloomfield Street.

1941 Due to planned construction of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and Battery Park underpass, reconstruction of the park is started. Plans call for the demolition of the fireboat station. Engine 57 is moved a short distance to "temporary quarters" on North River Pier 1.

1955 The new diesel-electric fireboat John D. McKean is assigned to Engine 57.

1959 Fireboats are changed from their previous Engine Company designations and are now known as Marine Companies. Engine 57 is designated Marine Co. 1.

Engine 57 medals:

THOMAS MALAVEY FF. ENG. 57 JAN. 29, 1900 1902 STRONG

JOHN A. SHEARER PILOT ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 PRENTICE

SVEN VICTOR HULL FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

ALBERT B. HOUSE, JR. FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

PETER A. MC NULTY FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

JOSEPH F. EARNEY FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

SAMUEL BRAISIN PROBIE ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

THOMAS J. WHITE ENGINEER ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 SCOTT

HARRY M. BIFFAR FF. ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

OTTO R. KUTZKE ENGINEER ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 JOHNSTON

Last FDNY member to hold the rank of Engineer of Steamer. Promoted off 1921 list. 45 years of service.

LAWRENCE S. GILLIAM ENGINEER ENG. 57 APR. 24, 1943 1944 BROOKMAN

Members of Engine 57 were awarded department medals for their heroism averting disaster on April 24, 1943 fighting a fire on the SS El Estero, a ship filled with ammunition.

The El Estero had taken on 1,365 tons of mixed munitions and was preparing to depart at approximately 5:30PM when a boiler flashback started a fire on oily water in her bilges which quickly grew out of control.

The initial report of fire aboard El Estero brought an immediate response of five fire trucks from the Jersey City Fire Department, two 30-foot fireboats and roughly 60 volunteers from the U.S. Coast Guard to battle and contain the flames aboard the ship, which was moored directly opposite two other fully loaded ammunition ships and two ammunition-laden consists of railroad boxcars. With over 5,000 tons of ammunition (comparable to a tactical nuclear weapon now in immediate danger of being set off by the fire on El Estero and with memories of the Black Tom explosion fresh on the minds of many at the scene, fire fighting efforts began in earnest. It was quickly discovered that the location and intensity of the fire prevented access to the ships' seacocks, making any attempt at scuttling the ship impossible, and the call went out to the New York City Fire Department, which in turn dispatched its two most powerful fireboats; Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey, to the scene.

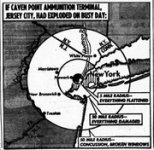

Arriving at 6:30 pm and immediately running hoses up to Coast Guardsmen on the burning ship, the fireboats took positions directly alongside El Estero as a trio of commercial tugboats made up a towline to her bow and began pulling her off the Caven Point Pier towards open waters on through The Narrows. Despite the high probability of the ship's volatile cargo exploding at any moment, the Coast Guardsmen, fire fighters and tug crews continued their efforts to contain the fire on El Estero to save as much of the ship and cargo as possible, but shortly after the tow began the Port Admiral of New York Harbor ordered the ship sunk. Shifting to a shallow area of water near Robbins Reef Light in Upper New York Bay, the fireboats began pumping their combined maximum capacity of 38,000 gallons of water per minute into El Estero's cargo holds, which succeeded in swamping the ship and sent her to the bottom shortly after 9PM with much of her superstructure still above the surface. With all hotspots declared extinguished by 11:30PM on the 24th, the all-clear for residents and businesses ringing New York Harbor was transmitted over the radio and what is considered to have been the single greatest threat to New York City during World War II passed without major incident or loss of life.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_El_Estero

http://www.capecodfd.com/pages%20special/Fireboats_FDNY_H1_Hist-Overview.htm

http://marine1fdny.com/history_new.php

Engine 57 Fire Fighter History - SS El Estero Fire

The Greatest Single Threat: Fire Aboard the SS El Estero ? April 24, 1943

From the August 2nd, 1945 NY PM Daily.

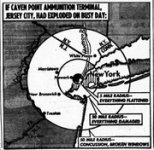

The mission carried out by the Caven Point Army Depot in New Jersey was one of the best-kept secrets of World War II. Located landside on the border of Jersey City and Bayonne and sitting alongside the terminal rail yards of several major railroads, the Caven Point Army Depot was designed and built to serve as a large-scale port of embarkation for soldiers and war materials bound overseas. Equipped with a mile-long finger pier that extended out from the mudflats into Upper New York Bay to a point roughly next to Liberty Island, the port facilities could accommodate loading or unloading operations of up to four large troopships or cargo vessels at the same time. Heavily utilized during World War I as both a departure and return point for U.S. servicemen, Caven Point remained fully operational between the wars and readily assumed its role when America entered World War II.

An aerial view of upper New York Bay from over Staten Island and looking North towards Manhattan. The Caven Point Pier is visible in the center-left of the photo with four MSTS Troopships tied up at the pier. The Berthing location of the El Estero on the day of her fire is highlighted by the Red arrow.

The outbreak of the World War II found the United States without a major ammunition supply point in the Northeast due in part to the disastrous sabotage and explosion at the nearby Black Tom Ammunition Depot in June 1916. Remembering the tragedies of Black Tom and the 1917 disaster in Halifax, Nova Scotia, many tri-state area residents and business owners vehemently opposed the idea of building a new ammunition terminal within New York Harbor, however the immediate need for an ammunition-loading terminal was so great in 1941 the order was issued?under a strict veil of secrecy?that Caven Point take up the additional role of handling munitions bound for the European and African theaters.

Though public knowledge about Caven Point?s additional duties would remain non-existent until the end of the war in Europe, the FDNY Marine Division was well briefed on the nature and scale of operations carried out at the facility. Every ship calling at Caven Point to load munitions was required to tender a copy of its blueprint and cargo hold plans to the Marine Division, so that in the event of an emergency, first responders could quickly and easily access, contain, and fight fires on any ammunition-laden ship. In addition to these measures, the U.S. Coast Guard maintained an active fire watch and sizeable fleet of pump-equipped patrol boats on a 24-hour alert around the pier, and the Bayonne Fire Department kept a fast reaction squad on alert as well. Every commercial tugboat calling the pier complex for ship-assist duties was required to have substantial external firefighting capabilities, to provide near-immediate response in the event of fire. Due in large part to these precautions, operations at Caven Point proceeded smoothly despite the hectic nature of operations at the now combined-use facility through 1942 and into 1943, when the buildup of men and material bound for England and Africa began to greatly swell the number of ships loading men, materials and munitions at the pier.

SS Alcoa Guide a near-sister ship to the SS El Estero and representative of how the El Estero likely appeared in April 1943.

One such vessel to call at Caven Point in April 1943 was the Panama-flagged SS El Estero, a 335-foot general cargo freighter operated by the United States Lines under contract to the U.S. Maritime Commission. Built in Staten Island as part of a three-ship class for the Southern Pacific Steamship Lines in 1920, the ship spent the first two decades of her service life engaged primarily in trade along the U.S. East Coast before being turned over to the U.S. government in June 1941 to help bolster the U.S. Merchant Marine Fleet. Though she was nearing the end of her useful service life, the ship was pressed into immediate service. By the time she came alongside the southeastern berth at the Caven Point finger pier, she was already a veteran of several harrowing trans-Atlantic convoy crossings, including the ill-fated Convoy PQ-13 in March 1942.

As a crew of U.S. Army stevedores made their way aboard ship and began to load the first of some 1,365 tons of mixed munitions from a string of railcars on the pier, the El Estero crew effected repairs to her aging and increasingly troublesome boiler system. By the time the last crate of ammunition was secured aboard, her hatches made ready for sea and the last of the stevedore work parties ashore on April 24, the El Estero had been joined at the finger pier by three other Europe-bound freighters. All three of her piermates were actively loading ammunition as her 5:30PM departure time drew near, and with a pair of tugs inbound to help pull her off the dock, El Estero?s engine room crew began light off her boilers to build up steam in preparation for departure. During this process an uncontained flashback occurred sending either a chance spark or a lick of flame into the ships bilges, which were filled with a thick mixture of oily seawater. Within minutes a fire had established itself and began to grow, filling the engine room with acrid black smoke. Realizing the gravity of the situation, crew quickly sounded El Estero?s fire alarm and set in motion what is considered to be the single greatest threat to New York Harbor?or any American city for that matter?during the entire of the Second World War.

This 1944 US Coast Guard photo was taken at the same location as the El Estero was berthed, and is representative of the environment at the pier on April 24th, 1943.

Word of the fire passed quickly from the El Estero to the pier, where a well-rehearsed response by the U.S. Coast Guard fire watch swung into action. Almost at once, a pair of patrol boats were onscene and ran hoses onto the ship while the Bayonne Fire Department dispatched two trucks and three engines to the ship. In spite of the rapid response, the fire burning deep within the ship showed no signs of abating and by 5:40PM the heat and smoke forced the evacuation of the ship?s engineering spaces and most of the below-deck midship areas. As the hope of a quick resolution went up with the now-thick plume of black smoke belching out of the ship?s air intakes, the sobering reality that the El Estero?s cargo could detonate at any moment came to grasp every person on the scene, only to be compounded by the fact that only feet away from the burning ship lay three other ammunition-laden ships and four full consists of ammunition-laden railcars. With a combined total of nearly 5,000 tons of explosives in immediate danger of being set off, a full-order detonation would have exposed most of New York Harbor, lower Manhattan, Brooklyn, Staten Island, Jersey City, Bayonne, and the strategically vital oil refinery-laden shores of New Jersey to a blast similar to a modern tactical nuclear weapon. With the progress of the Allied Mediterranean, North African, and South Pacific war efforts and the lives of thousands of civilians hinging on the successful containment of the fire aboard the El Estero, valiant Coast Guardsmen rallied volunteers to man the hoses aboard the burning ship and dispatched a call to the FDNY Marine Unit headquarters for urgent assistance.

From her position at Pier 1A in New York?s Battery, Fire Fighter?s crew had kept a trained eye on the ever-increasing pall of inky-black smoke rising over Caven Point, knowing full well there was a loaded ammunition ship on fire at the pier. Initial reports that the fire was being combated by onscene units were promising, but it was soon clear that the situation was taking a turn for the worse. Shortly before 6PM the order came to prepare for immediate action, and as her pilot came aboard with the plans for the El Estero tucked under his arm Fire Fighter?s engines rumbled to life and she was soon heading straight for Caven Point on what must have seemed like a guaranteed one-way trip.

Coming onscene shortly before 6:30PM both Fire Fighter and the John J. Harvey of Marine 2 took up positions on the starboard side of the burning ship. Their crews immediately passed hose lines up to the men on El Estero?s deck, lending substantial pumping capacity to the frantic effort to simultaneously cool the cargo hold ammunition and suppress the raging oil fire which was now totally out of control. Raising her aft tower monitor and sending a torrent of water down one of the engine room ventilation shafts, Fire Fighter?s crew were relieved to see a slight change in the color of the smoke coming from El Estero, a promising indication that the copious amounts of seawater were starting to have an effect on the fire. With their efforts soon coming under the direct command of Coast Guard Lt. Commander Arthur Pfister, a retired FDNY Battalion Chief and OIC of Coast Guard fireboats, efforts were mounted over the next half hour by firefighters and Coast Guardsmen to penetrate El Estero?s superstructure and attack the fire from the inside with chemical suppressants, all of which were rebuffed by intense heat and poisonous smoke conditions.

With an explosion still perilously imminent by 7PM despite strident firefighting efforts, Captain of the Port Rear Admiral Stanley Parker issued the order that the El Estero be immediately scuttled. But with her seacocks located deep below decks and therefore rendered inaccessible by the intense fire, the order could not be carried out. A hastily convened meeting pierside among Lt. Commander Pfister, his counterpart Lt. Commander John Stanley, and commercial tug Captain Ole Ericksen led to the decision to get the El Estero off the Caven Point Pier, away from the other troopships, and out into the open harbor, where the effects of any explosion would be lessened for the surrounding area. A crew of twenty volunteers remained onboard the furiously burning ship under the command of LCDR Stanley to continue firefighting efforts. The commercial tugboats Margaret Olsen, Ola G. Olsen, George R. Randolph, and Beatrice Bush formed up at the El Estero?s bow, where they tied into a steel hawser and began pulling the powerless ship off the pier.

By the time the slow convoy began to make headway into lower New York Harbor, the rapidly setting sun revealed to shoreside onlookers the ominous orange glow emanating from what seemed like the entire length of the burning ship in the harbor. With the spectacle only serving to attract more curious crowds to windows and along the shoreline, officials were left no option but to break the silence surrounding the events playing out at Caven Point. Shortly after 730PM, New York and New Jersey authorities warned residents by radio and through local air raid wardens that an explosion was imminent and to take shelter indoors and away from windows.

Back out in the harbor, Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey split up and were now on either side of the El Estero as she was slowly pulled south towards Robbins Reef, with each fireboat pumping at maximum capacity through their monitors and deck manifold hoses into the El Estero?s holds. Making painfully slow progress against the inbound tide, the ships finally reached the shallows immediately off the Robbins Reef Lighthouse shortly before 8PM and both of the El Estero?s anchors were dropped in approximately 40 feet of water. With the last of the volunteer ?crew? safely removed from the still-burning ship onto Coast Guard fireboats, Fire Fighter and the John J. Harvey directed their combined 36,000 gallons-per-minute pumping capacity into the El Estero?s holds in an all-out effort to sink the ship. Fire Fighter?s crew even went as far as utilizing her onboard air compressor and jackhammers to punch holes in El Estero?s hull to facilitate the flooding of her lower spaces. After another nervous hour of flooding efforts and several nerve-rattling low order detonations of deck-stowed fuel drums and ready anti-aircraft ammunition aboard El Estero, the efforts of Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey paid off as the ship finally took a list to Port and aided by several newly-added holes in her hull, flooded and sank to the bottom of New York Harbor with her decks and cargo holds completely awash shortly after 9PM. Fire Fighter and her crew stood by and continued to pour water onto the still-burning superstructure of the wrecked ship for another two hours, but by 9:45PM it was clear that the danger of an imminent explosion had passed.

El Estero sunk off Robbins Reef the morning after the fire still flying her red ?Baker? or hazardous cargo flag from her aft mast.

Released from her post shortly before midnight as the last of the visible fires aboard the El Estero were snuffed out, Fire Fighter and her crew returned to Pier 1A where personnel from the U.S. Navy were waiting to debrief them. With the official civilian ?All Clear? broadcast only moments before she tied up at her berth, the veil of wartime secrecy quickly descended onto the evening?s events and the actions of the men aboard Fire Fighter and the other ships that saved New York Harbor. It wouldn?t be until 1944 that the first official mention and awards for heroism were bestowed on the men who fought the fire aboard El Estero; and for their part, Fire Fighter?s duty crew that day were honored as follows:

Pilot John A. Shearer ? John H. Prentice Medal

Engineer Lawrence S. Gilliam ? Henry D. Bookman Medal

Engineer Otto R. Kutzke ? Albert S. Johnston Medal

Engineer Thomas J. White ? Walter Scott Medal

Fireman Harry M. Biffar ? Department Medal

Fireman Joseph F. Earney ? Department Medal

Fireman Albert B. House, Jr. ? Department Medal

Fireman Sven Victor Hull ? Department Medal

Fireman Peter A. McNulty ? Department Medal

Probie Samuel Braisin ? Department Medal

It would take until August 1945 for the U.S. Army to reveal the true scope of what took place at Caven Point during the war, along with the full details of what took place on April 24, 1943.

As for El Estero, the ship that almost destroyed New York Harbor remained in her sunken state for another four months as U.S. Navy, Coast Guard, and salvage experts decided on the best course of action for removing the still dangerous ammunition-laden hulk from the harbor. Eventually the decision was made to cofferdam the hull and raise the hulk without removing any of the cargo. In September 1943, the hulk of the El Estero was refloated and hastily towed out of New York Harbor to the open Atlantic Ocean, where she was set adrift and met her end as a live-fire target for U.S. Navy ships.

Refloated hunk of El Estero, it?s super structure wrapped in cofferdams, prepared for her tow into the Atlantic as a live fire target.

Due in large part to the secrecy surrounding the events of El Estero?s loss, her story remains largely unknown to the general public, but her untimely demise has left a very visible legacy in the waters around New York, specifically in Sandy Hook Bay. In August 1943, the U.S. Navy began high-priority construction of a new ammunition depot now known as Naval Weapons Station Earle which features a 2.9-mile pier designed to move the hazardous activity of loading and unloading munitions away from densely populated areas.

- from http://www.americasfireboat.org/ss-el-estero/

The Greatest Single Threat: Fire Aboard the SS El Estero ? April 24, 1943

From the August 2nd, 1945 NY PM Daily.

The mission carried out by the Caven Point Army Depot in New Jersey was one of the best-kept secrets of World War II. Located landside on the border of Jersey City and Bayonne and sitting alongside the terminal rail yards of several major railroads, the Caven Point Army Depot was designed and built to serve as a large-scale port of embarkation for soldiers and war materials bound overseas. Equipped with a mile-long finger pier that extended out from the mudflats into Upper New York Bay to a point roughly next to Liberty Island, the port facilities could accommodate loading or unloading operations of up to four large troopships or cargo vessels at the same time. Heavily utilized during World War I as both a departure and return point for U.S. servicemen, Caven Point remained fully operational between the wars and readily assumed its role when America entered World War II.

An aerial view of upper New York Bay from over Staten Island and looking North towards Manhattan. The Caven Point Pier is visible in the center-left of the photo with four MSTS Troopships tied up at the pier. The Berthing location of the El Estero on the day of her fire is highlighted by the Red arrow.

The outbreak of the World War II found the United States without a major ammunition supply point in the Northeast due in part to the disastrous sabotage and explosion at the nearby Black Tom Ammunition Depot in June 1916. Remembering the tragedies of Black Tom and the 1917 disaster in Halifax, Nova Scotia, many tri-state area residents and business owners vehemently opposed the idea of building a new ammunition terminal within New York Harbor, however the immediate need for an ammunition-loading terminal was so great in 1941 the order was issued?under a strict veil of secrecy?that Caven Point take up the additional role of handling munitions bound for the European and African theaters.

Though public knowledge about Caven Point?s additional duties would remain non-existent until the end of the war in Europe, the FDNY Marine Division was well briefed on the nature and scale of operations carried out at the facility. Every ship calling at Caven Point to load munitions was required to tender a copy of its blueprint and cargo hold plans to the Marine Division, so that in the event of an emergency, first responders could quickly and easily access, contain, and fight fires on any ammunition-laden ship. In addition to these measures, the U.S. Coast Guard maintained an active fire watch and sizeable fleet of pump-equipped patrol boats on a 24-hour alert around the pier, and the Bayonne Fire Department kept a fast reaction squad on alert as well. Every commercial tugboat calling the pier complex for ship-assist duties was required to have substantial external firefighting capabilities, to provide near-immediate response in the event of fire. Due in large part to these precautions, operations at Caven Point proceeded smoothly despite the hectic nature of operations at the now combined-use facility through 1942 and into 1943, when the buildup of men and material bound for England and Africa began to greatly swell the number of ships loading men, materials and munitions at the pier.

SS Alcoa Guide a near-sister ship to the SS El Estero and representative of how the El Estero likely appeared in April 1943.

One such vessel to call at Caven Point in April 1943 was the Panama-flagged SS El Estero, a 335-foot general cargo freighter operated by the United States Lines under contract to the U.S. Maritime Commission. Built in Staten Island as part of a three-ship class for the Southern Pacific Steamship Lines in 1920, the ship spent the first two decades of her service life engaged primarily in trade along the U.S. East Coast before being turned over to the U.S. government in June 1941 to help bolster the U.S. Merchant Marine Fleet. Though she was nearing the end of her useful service life, the ship was pressed into immediate service. By the time she came alongside the southeastern berth at the Caven Point finger pier, she was already a veteran of several harrowing trans-Atlantic convoy crossings, including the ill-fated Convoy PQ-13 in March 1942.

As a crew of U.S. Army stevedores made their way aboard ship and began to load the first of some 1,365 tons of mixed munitions from a string of railcars on the pier, the El Estero crew effected repairs to her aging and increasingly troublesome boiler system. By the time the last crate of ammunition was secured aboard, her hatches made ready for sea and the last of the stevedore work parties ashore on April 24, the El Estero had been joined at the finger pier by three other Europe-bound freighters. All three of her piermates were actively loading ammunition as her 5:30PM departure time drew near, and with a pair of tugs inbound to help pull her off the dock, El Estero?s engine room crew began light off her boilers to build up steam in preparation for departure. During this process an uncontained flashback occurred sending either a chance spark or a lick of flame into the ships bilges, which were filled with a thick mixture of oily seawater. Within minutes a fire had established itself and began to grow, filling the engine room with acrid black smoke. Realizing the gravity of the situation, crew quickly sounded El Estero?s fire alarm and set in motion what is considered to be the single greatest threat to New York Harbor?or any American city for that matter?during the entire of the Second World War.

This 1944 US Coast Guard photo was taken at the same location as the El Estero was berthed, and is representative of the environment at the pier on April 24th, 1943.

Word of the fire passed quickly from the El Estero to the pier, where a well-rehearsed response by the U.S. Coast Guard fire watch swung into action. Almost at once, a pair of patrol boats were onscene and ran hoses onto the ship while the Bayonne Fire Department dispatched two trucks and three engines to the ship. In spite of the rapid response, the fire burning deep within the ship showed no signs of abating and by 5:40PM the heat and smoke forced the evacuation of the ship?s engineering spaces and most of the below-deck midship areas. As the hope of a quick resolution went up with the now-thick plume of black smoke belching out of the ship?s air intakes, the sobering reality that the El Estero?s cargo could detonate at any moment came to grasp every person on the scene, only to be compounded by the fact that only feet away from the burning ship lay three other ammunition-laden ships and four full consists of ammunition-laden railcars. With a combined total of nearly 5,000 tons of explosives in immediate danger of being set off, a full-order detonation would have exposed most of New York Harbor, lower Manhattan, Brooklyn, Staten Island, Jersey City, Bayonne, and the strategically vital oil refinery-laden shores of New Jersey to a blast similar to a modern tactical nuclear weapon. With the progress of the Allied Mediterranean, North African, and South Pacific war efforts and the lives of thousands of civilians hinging on the successful containment of the fire aboard the El Estero, valiant Coast Guardsmen rallied volunteers to man the hoses aboard the burning ship and dispatched a call to the FDNY Marine Unit headquarters for urgent assistance.

From her position at Pier 1A in New York?s Battery, Fire Fighter?s crew had kept a trained eye on the ever-increasing pall of inky-black smoke rising over Caven Point, knowing full well there was a loaded ammunition ship on fire at the pier. Initial reports that the fire was being combated by onscene units were promising, but it was soon clear that the situation was taking a turn for the worse. Shortly before 6PM the order came to prepare for immediate action, and as her pilot came aboard with the plans for the El Estero tucked under his arm Fire Fighter?s engines rumbled to life and she was soon heading straight for Caven Point on what must have seemed like a guaranteed one-way trip.

Coming onscene shortly before 6:30PM both Fire Fighter and the John J. Harvey of Marine 2 took up positions on the starboard side of the burning ship. Their crews immediately passed hose lines up to the men on El Estero?s deck, lending substantial pumping capacity to the frantic effort to simultaneously cool the cargo hold ammunition and suppress the raging oil fire which was now totally out of control. Raising her aft tower monitor and sending a torrent of water down one of the engine room ventilation shafts, Fire Fighter?s crew were relieved to see a slight change in the color of the smoke coming from El Estero, a promising indication that the copious amounts of seawater were starting to have an effect on the fire. With their efforts soon coming under the direct command of Coast Guard Lt. Commander Arthur Pfister, a retired FDNY Battalion Chief and OIC of Coast Guard fireboats, efforts were mounted over the next half hour by firefighters and Coast Guardsmen to penetrate El Estero?s superstructure and attack the fire from the inside with chemical suppressants, all of which were rebuffed by intense heat and poisonous smoke conditions.

With an explosion still perilously imminent by 7PM despite strident firefighting efforts, Captain of the Port Rear Admiral Stanley Parker issued the order that the El Estero be immediately scuttled. But with her seacocks located deep below decks and therefore rendered inaccessible by the intense fire, the order could not be carried out. A hastily convened meeting pierside among Lt. Commander Pfister, his counterpart Lt. Commander John Stanley, and commercial tug Captain Ole Ericksen led to the decision to get the El Estero off the Caven Point Pier, away from the other troopships, and out into the open harbor, where the effects of any explosion would be lessened for the surrounding area. A crew of twenty volunteers remained onboard the furiously burning ship under the command of LCDR Stanley to continue firefighting efforts. The commercial tugboats Margaret Olsen, Ola G. Olsen, George R. Randolph, and Beatrice Bush formed up at the El Estero?s bow, where they tied into a steel hawser and began pulling the powerless ship off the pier.

By the time the slow convoy began to make headway into lower New York Harbor, the rapidly setting sun revealed to shoreside onlookers the ominous orange glow emanating from what seemed like the entire length of the burning ship in the harbor. With the spectacle only serving to attract more curious crowds to windows and along the shoreline, officials were left no option but to break the silence surrounding the events playing out at Caven Point. Shortly after 730PM, New York and New Jersey authorities warned residents by radio and through local air raid wardens that an explosion was imminent and to take shelter indoors and away from windows.

Back out in the harbor, Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey split up and were now on either side of the El Estero as she was slowly pulled south towards Robbins Reef, with each fireboat pumping at maximum capacity through their monitors and deck manifold hoses into the El Estero?s holds. Making painfully slow progress against the inbound tide, the ships finally reached the shallows immediately off the Robbins Reef Lighthouse shortly before 8PM and both of the El Estero?s anchors were dropped in approximately 40 feet of water. With the last of the volunteer ?crew? safely removed from the still-burning ship onto Coast Guard fireboats, Fire Fighter and the John J. Harvey directed their combined 36,000 gallons-per-minute pumping capacity into the El Estero?s holds in an all-out effort to sink the ship. Fire Fighter?s crew even went as far as utilizing her onboard air compressor and jackhammers to punch holes in El Estero?s hull to facilitate the flooding of her lower spaces. After another nervous hour of flooding efforts and several nerve-rattling low order detonations of deck-stowed fuel drums and ready anti-aircraft ammunition aboard El Estero, the efforts of Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey paid off as the ship finally took a list to Port and aided by several newly-added holes in her hull, flooded and sank to the bottom of New York Harbor with her decks and cargo holds completely awash shortly after 9PM. Fire Fighter and her crew stood by and continued to pour water onto the still-burning superstructure of the wrecked ship for another two hours, but by 9:45PM it was clear that the danger of an imminent explosion had passed.

El Estero sunk off Robbins Reef the morning after the fire still flying her red ?Baker? or hazardous cargo flag from her aft mast.

Released from her post shortly before midnight as the last of the visible fires aboard the El Estero were snuffed out, Fire Fighter and her crew returned to Pier 1A where personnel from the U.S. Navy were waiting to debrief them. With the official civilian ?All Clear? broadcast only moments before she tied up at her berth, the veil of wartime secrecy quickly descended onto the evening?s events and the actions of the men aboard Fire Fighter and the other ships that saved New York Harbor. It wouldn?t be until 1944 that the first official mention and awards for heroism were bestowed on the men who fought the fire aboard El Estero; and for their part, Fire Fighter?s duty crew that day were honored as follows:

Pilot John A. Shearer ? John H. Prentice Medal

Engineer Lawrence S. Gilliam ? Henry D. Bookman Medal

Engineer Otto R. Kutzke ? Albert S. Johnston Medal

Engineer Thomas J. White ? Walter Scott Medal

Fireman Harry M. Biffar ? Department Medal

Fireman Joseph F. Earney ? Department Medal

Fireman Albert B. House, Jr. ? Department Medal

Fireman Sven Victor Hull ? Department Medal

Fireman Peter A. McNulty ? Department Medal

Probie Samuel Braisin ? Department Medal

It would take until August 1945 for the U.S. Army to reveal the true scope of what took place at Caven Point during the war, along with the full details of what took place on April 24, 1943.

As for El Estero, the ship that almost destroyed New York Harbor remained in her sunken state for another four months as U.S. Navy, Coast Guard, and salvage experts decided on the best course of action for removing the still dangerous ammunition-laden hulk from the harbor. Eventually the decision was made to cofferdam the hull and raise the hulk without removing any of the cargo. In September 1943, the hulk of the El Estero was refloated and hastily towed out of New York Harbor to the open Atlantic Ocean, where she was set adrift and met her end as a live-fire target for U.S. Navy ships.

Refloated hunk of El Estero, it?s super structure wrapped in cofferdams, prepared for her tow into the Atlantic as a live fire target.

Due in large part to the secrecy surrounding the events of El Estero?s loss, her story remains largely unknown to the general public, but her untimely demise has left a very visible legacy in the waters around New York, specifically in Sandy Hook Bay. In August 1943, the U.S. Navy began high-priority construction of a new ammunition depot now known as Naval Weapons Station Earle which features a 2.9-mile pier designed to move the hazardous activity of loading and unloading munitions away from densely populated areas.

- from http://www.americasfireboat.org/ss-el-estero/

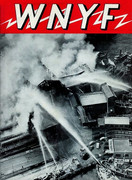

From WW II WNYFs - Marine Division:

1. Following Pearl Harbor, NYC fireboats patrolled the harbor area 24/7. They only returned to their berths to change crews and fuel.

2. Per US Navy guidance, fireboats were painted over in Navy gray

3. Fireboats assisted in U Boat harbor security screens

4. Vessel codes were used to dispatch fireboats to incidents related to large troop and cargo ship incidents - reports were completed by phone after jobs - radio silence was enforced for security.

5. Most of the logistical support for the war came from NYC harbor areas - for security, the busy harbor operated in black-out restrictions at night

6. Half our troops and 1/3 of all war supplies departed through NYC harbor - ammunition ships, fuel supply ships were constant major incident threat - numerous ship fires took place and were down-played for security reasons

7. The SS El Estro fire, for example, a "potential atom bomb, was defused by FDNY fireboat crews and the US Navy - all crewmembers were decorated

8. A Manhattan Beach summer resort area was taken over by the Coast Guard, during WW II part of the US Navy, and 180,000 were stationed there by 1942 with 24 fireboats to assist FDNY

9. Ship convoys leaving for Europe were "spread-loaded" due to submarine attacks - the result was that all cargo ships could be loaded with explosives, ammunition and other hazardous materials without markings

10. Frequently, ships in the vicinity of NYC with on-board fires would head for NY harbor for FDNY and Coast Guard help

11. NYC military facilities to protect included:

- NY Port of Embarkation (NYPE) facilities and piers, which moved over 3,000,000 troops and 63,000,000 tons of supplies. NYPE had its own fire units.

- Brooklyn Army Base, 1st Ave and 58th St Bklyn - "largest warehouse in the world" - 48 acres of logistical supplies

- Brooklyn Navy Yard

- Bush Terminal - 29th St to 46th St Bklyn - 100s of ships, 1000s of railroad cars and trucks were unloaded weekly

- Staten Island Terminal, Stapleton - 400,000 sq ft of storage space and tracks for 250 railroad cars

- Floyd Bennett Field, Jamaica Bay - 750 weekly flights of military personnel and cargo

- North River terminal, 12th Ave and 46th St - 7 large piers for embarcation (troop departure) and debarcation (troop return)

- Craven Point NJ - ammunitions and explosive storage

- Howland Hook terminal, Staten Island - petroleum storage to support war

- Fort Hamilton, Fort Wadsworth, Fort Totten, Governor's Island, Miller Field and other NYC military bases located along NYC waterfront

12. Many serious incidents, collisions, barge fires and ship fires ocurred with little publicity due to war security

13. FDNY fireboats were called outside NYC harbor area to assist with fires, explosions and emergencies - a submarine net was in place across the entrance to the harbor - fireboats had to pass through security check points to enter and leave

14. FDNY crews were shorthanded during WW II with large number of members serving in military

1. Following Pearl Harbor, NYC fireboats patrolled the harbor area 24/7. They only returned to their berths to change crews and fuel.

2. Per US Navy guidance, fireboats were painted over in Navy gray

3. Fireboats assisted in U Boat harbor security screens

4. Vessel codes were used to dispatch fireboats to incidents related to large troop and cargo ship incidents - reports were completed by phone after jobs - radio silence was enforced for security.

5. Most of the logistical support for the war came from NYC harbor areas - for security, the busy harbor operated in black-out restrictions at night

6. Half our troops and 1/3 of all war supplies departed through NYC harbor - ammunition ships, fuel supply ships were constant major incident threat - numerous ship fires took place and were down-played for security reasons

7. The SS El Estro fire, for example, a "potential atom bomb, was defused by FDNY fireboat crews and the US Navy - all crewmembers were decorated

8. A Manhattan Beach summer resort area was taken over by the Coast Guard, during WW II part of the US Navy, and 180,000 were stationed there by 1942 with 24 fireboats to assist FDNY

9. Ship convoys leaving for Europe were "spread-loaded" due to submarine attacks - the result was that all cargo ships could be loaded with explosives, ammunition and other hazardous materials without markings

10. Frequently, ships in the vicinity of NYC with on-board fires would head for NY harbor for FDNY and Coast Guard help

11. NYC military facilities to protect included:

- NY Port of Embarkation (NYPE) facilities and piers, which moved over 3,000,000 troops and 63,000,000 tons of supplies. NYPE had its own fire units.

- Brooklyn Army Base, 1st Ave and 58th St Bklyn - "largest warehouse in the world" - 48 acres of logistical supplies

- Brooklyn Navy Yard

- Bush Terminal - 29th St to 46th St Bklyn - 100s of ships, 1000s of railroad cars and trucks were unloaded weekly

- Staten Island Terminal, Stapleton - 400,000 sq ft of storage space and tracks for 250 railroad cars

- Floyd Bennett Field, Jamaica Bay - 750 weekly flights of military personnel and cargo

- North River terminal, 12th Ave and 46th St - 7 large piers for embarcation (troop departure) and debarcation (troop return)

- Craven Point NJ - ammunitions and explosive storage

- Howland Hook terminal, Staten Island - petroleum storage to support war

- Fort Hamilton, Fort Wadsworth, Fort Totten, Governor's Island, Miller Field and other NYC military bases located along NYC waterfront

12. Many serious incidents, collisions, barge fires and ship fires ocurred with little publicity due to war security

13. FDNY fireboats were called outside NYC harbor area to assist with fires, explosions and emergencies - a submarine net was in place across the entrance to the harbor - fireboats had to pass through security check points to enter and leave

14. FDNY crews were shorthanded during WW II with large number of members serving in military

Engine 51 (Marine) Manhattan, Staten Island BECAME MARINE 9

Engine 51 organized Pier 42 East River 1883

Engine 51 moved foot of W 13th Street Hudson River 1884

Engine 51 moved foot of Bloomfield Street Hudson River 1892

Engine 51 moved foot of 99th Street Harlem River 1903

Engine 51 moved St. George Staten Island 1908

Engine 51 disbanded 1916

Engine 51 reorganized foot of Hyatt Street 1922

Engine 51 disbanded 1934

Engine 51 reorganized foot of Hyatt Street 1938

Engine 51 moved foot of Hannah Street 1947

Engine 51 disbanded 1948

Engine 51 reorganized Pier 6 Hannah Street 1949

Engine 51 disbanded to form Marine 9 1959

Engine 51 fireboats:

"Zophar Mills"

1883-1934

120' x 25' x 12'

6000 GPM

Built by Prusey and Jones Ship Building Company Wilmington, Delaware

Zophar Mills was named after volunteer firefighter who did not miss a fire in 45 years of service

"William L. Strong"

1938-1948

100' x 24' x 12.6'

6500 GPM

Designed by H deB Parsons

Built by J. H. Dialogue & Son

Steel hull

203 gross tons

10 knots

Coal Fired

"George B. McClellan"

1949-1953

117' x 24' x 9'6"

7000 GPM

Built by New York Shipping Co., Camden, NJ

Steel hull

Coal fired

3 deck pipes

16 discharges

"Cornelius W. Lawrence"

1953-1954

104'6" x 23'6" x 9'

7000 GPM

Built by Alexander Miller & Bros, Jersey City, NJ

Coal fired

Steam turbine driven pumps

Lower profile super structure

No tower mast

"William J. Gaynor"

1954-1958

118' x 25' x 13.4'

7000 GPM

Built by John W. Sullivan & Company, Elizabethport, NJ

Last coal fired NY fireboat built

14 knots

Converted from coal to oil in 1937

"H. Sylvia A. H. G. Wilks"

1958-1959

105'6" x 27' x 9'

8000 GPM

Built by John Mathis Shipyards, Camden, NJ

5 deck monitors

500 gallon foam tank

Engine 51 - General Slocum Disaster June 15, 1904:

Engine 51 responded to General Slocum steamship fire and performed firefighting, rescue and recovery work. 1021 perished.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/a-spectacle-of-horror-the-burning-of-the-general-slocum-104712974/

http://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2017/06/remembering-general-slocum-disaster-june-15-1904.html

Engine 51 Medals:

WILLIAM H. ASBROCK FF. ENG. 51 APR. 24, 1943 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

Engine 51 organized Pier 42 East River 1883

Engine 51 moved foot of W 13th Street Hudson River 1884

Engine 51 moved foot of Bloomfield Street Hudson River 1892

Engine 51 moved foot of 99th Street Harlem River 1903

Engine 51 moved St. George Staten Island 1908

Engine 51 disbanded 1916

Engine 51 reorganized foot of Hyatt Street 1922

Engine 51 disbanded 1934

Engine 51 reorganized foot of Hyatt Street 1938

Engine 51 moved foot of Hannah Street 1947

Engine 51 disbanded 1948

Engine 51 reorganized Pier 6 Hannah Street 1949

Engine 51 disbanded to form Marine 9 1959

Engine 51 fireboats:

"Zophar Mills"

1883-1934

120' x 25' x 12'

6000 GPM

Built by Prusey and Jones Ship Building Company Wilmington, Delaware

Zophar Mills was named after volunteer firefighter who did not miss a fire in 45 years of service

"William L. Strong"

1938-1948

100' x 24' x 12.6'

6500 GPM

Designed by H deB Parsons

Built by J. H. Dialogue & Son

Steel hull

203 gross tons

10 knots

Coal Fired

"George B. McClellan"

1949-1953

117' x 24' x 9'6"

7000 GPM

Built by New York Shipping Co., Camden, NJ

Steel hull

Coal fired

3 deck pipes

16 discharges

"Cornelius W. Lawrence"

1953-1954

104'6" x 23'6" x 9'

7000 GPM

Built by Alexander Miller & Bros, Jersey City, NJ

Coal fired

Steam turbine driven pumps

Lower profile super structure

No tower mast

"William J. Gaynor"

1954-1958

118' x 25' x 13.4'

7000 GPM

Built by John W. Sullivan & Company, Elizabethport, NJ

Last coal fired NY fireboat built

14 knots

Converted from coal to oil in 1937

"H. Sylvia A. H. G. Wilks"

1958-1959

105'6" x 27' x 9'

8000 GPM

Built by John Mathis Shipyards, Camden, NJ

5 deck monitors

500 gallon foam tank

Engine 51 - General Slocum Disaster June 15, 1904:

Engine 51 responded to General Slocum steamship fire and performed firefighting, rescue and recovery work. 1021 perished.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/a-spectacle-of-horror-the-burning-of-the-general-slocum-104712974/

http://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2017/06/remembering-general-slocum-disaster-june-15-1904.html

Engine 51 Medals:

WILLIAM H. ASBROCK FF. ENG. 51 APR. 24, 1943 1943 1944 DEPARTMENT

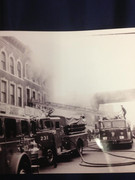

Fire fought by Engine 51 - Staten Island, NY Ferry Terminal Fire, Richmond Box 5-5-13, June 25, 1946

WNYF OCTOBER 1946:

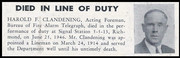

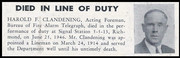

LODD:

HAROLD F. CLANDENING, ACTING FOREMAN, BUREAU OF FIRE ALARM TELEGRAPH, RICHMOND BOX 5-5-13, JUNE 25, 1946

RIP. Never forget.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9oYXTbVEbU

2 DEAD IN FIRE ON STATEN ISLE, LOSS 2 MILLION, 34 PERSONS HURT, ST. GEORGE FERRY HOUSE DESTROYED.

Submitted by Stu Beitler New York | Fires | 1946

New York, (AP) -- Two persons burned to death and 34 were overcome or injured yesterday in a nine-alarm, $2,000,000 blaze which engulfed Staten Island's St. George ferry terminal shortly after it had been emptied of 500 passengers.

The dead were MRS. CORNELIUS WHITE, a ticket agent, and Fireman HAROLD CLENDENING, 59. Both lived on Staten Island.

Sparks from a short-circuit on a Staten Island electric train started the fire, about 2 p.m., said Assistant District Attorney Herman Methfessel.

Within five minutes the 40-year-old rambling wooden structure was a mass of flames, fed by paint, oil and grease in a basement shop. Giant billows of white smoke poured from the building.

CLENDENING was trapped by the fast-spreading flames when he tried to rescue MRS. WHITE.

Fourteen persons were injured and 20 others, mostly firemen, police and ferry employes, were overcome by smoke and heat. It was two hours before the fire was brought under control.

Five hundred passengers had just boarded a Manhattan-bound ferry and the station was nearly empty when the first cry of "fire" echoed thru the high-ceilinged, three and a half story ferry house.

Two other ferries, idling in their slips, had time to pull away before the ferryhouse and all four slips were destroyed.

The flames spread a block down-shore to the main platform of the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad. Twenty coaches were destroyed.

The thousands of commuters who daily use the Staten Island ferries from Manhattan, the largest ferry boats in service in the city, were forced to seek other means of transportation home.

Coast guards and fire department boats fought the blaze from Upper New York bay while fire apparatus from Brooklyn, Manhattan and Richmond Boros responded to nine alarms sounded within half an hour after the fire broke out.

Manhattan fire companies raced thru Holland tunnel to the Jersey side of the Hudson River and reached the scene via the Bayonne-Staten Island bridge.

Other fire fighting equipment moved to the blaze by the electric ferry from Brooklyn.

Meanwhile, dense columns of smoke and tongues of flame over the Lower Manhattan horizon attracted thousands of pedestrians and motorists, snarling traffic. Police loudspeakers were set up at the Battery and South Ferry districts to control crowds.

Staten Island ferry service to South Ferry, Manhatten, and 39th in Brooklyn, was temporarily suspended. Between 35,000 and 50,000 commuters daily use the ferry service on Staten Island, which has a population of 183,000. The St. George ferry house was built in 1906. Methfessel estimated damage at more than $2,000,000.

One hundred telephones in two Staten Island exchanges were out of order due to a burned out cable, the New York Telephone Co. said.

- FROM GENDISASTERS.COM http://www.gendisasters.com/new-york/19090/staten-island-ny-ferry-terminal-fire-june-1946

STATEN ISLAND ADVANCE - https://www.silive.com/specialreports/index.ssf/2011/03/deadly_fire_destroys_staten_is.html

WNYF OCTOBER 1946:

LODD:

HAROLD F. CLANDENING, ACTING FOREMAN, BUREAU OF FIRE ALARM TELEGRAPH, RICHMOND BOX 5-5-13, JUNE 25, 1946

RIP. Never forget.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9oYXTbVEbU

2 DEAD IN FIRE ON STATEN ISLE, LOSS 2 MILLION, 34 PERSONS HURT, ST. GEORGE FERRY HOUSE DESTROYED.

Submitted by Stu Beitler New York | Fires | 1946

New York, (AP) -- Two persons burned to death and 34 were overcome or injured yesterday in a nine-alarm, $2,000,000 blaze which engulfed Staten Island's St. George ferry terminal shortly after it had been emptied of 500 passengers.

The dead were MRS. CORNELIUS WHITE, a ticket agent, and Fireman HAROLD CLENDENING, 59. Both lived on Staten Island.

Sparks from a short-circuit on a Staten Island electric train started the fire, about 2 p.m., said Assistant District Attorney Herman Methfessel.

Within five minutes the 40-year-old rambling wooden structure was a mass of flames, fed by paint, oil and grease in a basement shop. Giant billows of white smoke poured from the building.

CLENDENING was trapped by the fast-spreading flames when he tried to rescue MRS. WHITE.

Fourteen persons were injured and 20 others, mostly firemen, police and ferry employes, were overcome by smoke and heat. It was two hours before the fire was brought under control.

Five hundred passengers had just boarded a Manhattan-bound ferry and the station was nearly empty when the first cry of "fire" echoed thru the high-ceilinged, three and a half story ferry house.

Two other ferries, idling in their slips, had time to pull away before the ferryhouse and all four slips were destroyed.

The flames spread a block down-shore to the main platform of the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad. Twenty coaches were destroyed.

The thousands of commuters who daily use the Staten Island ferries from Manhattan, the largest ferry boats in service in the city, were forced to seek other means of transportation home.

Coast guards and fire department boats fought the blaze from Upper New York bay while fire apparatus from Brooklyn, Manhattan and Richmond Boros responded to nine alarms sounded within half an hour after the fire broke out.

Manhattan fire companies raced thru Holland tunnel to the Jersey side of the Hudson River and reached the scene via the Bayonne-Staten Island bridge.

Other fire fighting equipment moved to the blaze by the electric ferry from Brooklyn.

Meanwhile, dense columns of smoke and tongues of flame over the Lower Manhattan horizon attracted thousands of pedestrians and motorists, snarling traffic. Police loudspeakers were set up at the Battery and South Ferry districts to control crowds.

Staten Island ferry service to South Ferry, Manhatten, and 39th in Brooklyn, was temporarily suspended. Between 35,000 and 50,000 commuters daily use the ferry service on Staten Island, which has a population of 183,000. The St. George ferry house was built in 1906. Methfessel estimated damage at more than $2,000,000.

One hundred telephones in two Staten Island exchanges were out of order due to a burned out cable, the New York Telephone Co. said.

- FROM GENDISASTERS.COM http://www.gendisasters.com/new-york/19090/staten-island-ny-ferry-terminal-fire-june-1946

STATEN ISLAND ADVANCE - https://www.silive.com/specialreports/index.ssf/2011/03/deadly_fire_destroys_staten_is.html

Staten Island Ferry Terminal Fire (Manhattan terminal)- 4th Alarm - 9/8/91

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrJ08WtQnUI

NY TIMES - BIG FIRE DESTROYS TERMINAL OF FERRY TO STATEN ISLAND

By ROBERT D. MCFADDEN

The New York Times Archives

A spectacular fire of suspicious origin destroyed the ceiling and roof of the Staten Island ferry's cavernous Manhattan terminal yesterday morning, disrupting service for thousands of riders on a commuter workhorse that is one of New York City's most glamorous sightseeing attractions.

As flaming chunks of asbestos-laden ceiling debris cascaded onto the passenger concourse and dense clouds of dark smoke billowed over New York Harbor just after 8 A.M., scores of early-morning riders and shopkeepers fled the terminal in panic, and a quiet Sunday amid the ghostly empty skyscrapers of lower Manhattan was turned into a war zone of wailing sirens and firefighting apparatus.

With the terminal temporarily unusable, authorities shifted ferry operations to a Coast Guard slip next door and promised reduced, but free, service to 70,000 weekday riders starting with this morning's rush. Three boats an hour instead of four will make the 20-minute harbor crossing between Manhattan and Staten Island. The ride normally costs 50 cents. More Time and No Cars

No cars will be carried on the ferries and, with highways expected to be crowded because of construction work and heavy traffic associated with the Jewish New Year, Staten Island commuters were urged to allow up to 45 minutes more to cope with confusion and delays.

It is unclear how long the stopgap measures will be needed. Lucius J. Riccio, the city's Transportation Commissioner, said the undamaged lower level of the ferry terminal, where the boats enter the slips and take on cars and some passengers, might be available for use within days if no asbestos dangers are found and docking mechanisms are undamaged.

But he warned that it would be "months, perhaps years" before the roof and ceiling of the normally bustling upper-level passenger concourse could be replaced and normal service restored to the terminal, where orange boats take blase commuters and captivated tourists across a busy harbor that features dramatic skyline views, Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty.

Fire marshals had no proof of arson but called the fire suspicious because the flames seemed to burst into a conflagration within minutes.

As yesterday's blaze raked one of the city's best-known terminals, at least 20 people were injured, most of them firefighters and police officers who suffered smoke inhalation. Environmental officials said that asbestos insulation tumbling from the burning cockloft apparently contaminated the huge waiting room and the clothing and equipment of scores of firefighters.

Witnesses told of first smelling smoke on the upper-level concourse, then sudden panic as flames burst from the ceiling 30 feet overhead and chunks of burning ceiling began to rain down. "Everybody was pushing and running," said Siva Wignaragah, a vendor at the newsstand in the terminal.

Out on the harbor aboard an incoming ferryboat, Hasan Djelshevic, a pizza vendor going to work, stared with awe and apprehension at the enormous cloud of smoke rising ahead. "A lot of people were scared -- me too," he said after his ferry docked at the Coast Guard slip. Already, firefighters were swarming over the scene, and flames were shooting skyward from the terminal's roof.

Within minutes, four alarms had been transmitted because of the wide, swift spread of the flames. Eventually, more than 200 firefighters battled the blaze, using nearly 40 trucks, including four tower ladders that rose 75 to 90 feet into the air to shoot water down on the flames, and three fireboats that pulled up at dockside and shot enormous streams of harbor water into the burning building.

The fire, first reported at 8:12 A.M., was declared under control shortly before noon, but firefighters continued to struggle all afternoon with pockets of fire in nooks and crannies of the cockloft -- the space between ceiling and roof that was filled with heating, ventilating and air-conditioning ducts, electrical wiring, asbestos and structural supports. Asbestos Tests Close IRT Stop

Although no other toxic chemicals were reported, Albert F. Appleton, the city's Commissioner of Environmental Protection, said several hundred pounds of asbestos had been wrapped around heating ducts and had been scattered by the fire and the water used to fight it.

Inspectors were conducting tests to determine the extent of the danger, but scores of firefighters were decontaminated as a precaution and the IRT subway stop under the terminal was closed pending a study of asbestos dangers.

City officials said it might take months to repair the terminal, an architecturally undistinguished, sea-green, concrete-and-glass building erected a half-century ago on the site of ferry operations that date to Cornelius Vanderbilt's original enterprise in the early 19th century.

The four-hour fire left the terminal temporarily unusable, a dripping, debris-clogged shell that was evidently structurally sound but had gaping holes open to the sky above the passenger and shop concourse. But even as firefighters battled the stubborn blaze with powerful streams of water, city transportation officials shifted arriving ferries to the Coast Guard slip and said they would use that terminal for the immediate future.

Bracing for a chaotic morning rush today, officials said the Staten Island ferry, which normally runs four trips an hour at the busiest times -- two carrying 6,000 riders each and two carrying 3,500 each, plus cars -- would cut service to three boats an hour, with departures every 20 minutes instead of every 15.

The Coast Guard slip is big enough to accommodate Staten Island ferryboats and their large passenger loads, but because of anticipated congestion it was decided to ban cars.

City officials said that to relieve some of the congestion at the Coast Guard slip, they were considering using Pier 11, just south of Wall Street on the East River, as an additional ferry terminal, if soundings show the water is deep enough and engineers approve the pier as structurally sound.

The fire was yet another hardship for the city's troubled mass transit system, which saw five subway riders killed and 200 injured on Aug. 28 when a train -- driven by a motorman authorities said was drunk -- derailed near Union Square, snarling traffic on Manhattan's only East Side line for a week.

The Staten Island Ferry, a major link in the city's transportation system, carries 22 million riders a year between Battery Park in Manhattan and St. George Terminal on Staten Island. St. George Terminal was heavily damaged by a fire in 1946.

The Manhattan terminal, first built in 1907 and rebuilt and enlarged in 1957, is a two-level, 200-feet-long building that for all the nostalgia of the ferry it serves, is a down-at-the-heels place with scarred benches and small shops: fast-foot outlets, newsstands, a florist, and other businesses. Troubadours sometimes offer music or poetry, but homeless people and panhandlers are often found amid the passing crowds.

The city's Fire Commissioner, Carlos M. Rivera, said fire marshals were still trying to determine the cause of the blaze and the precise spot where it began. But by day's end, officials said they believed it started in the cockloft on the water-side of the terminal.

Though the fire was labeled suspicious, fire marshals were not saying that it was necessarily the work of an arsonist. To start the fire, said Deputy Chief Robert Beier of the First Division in Lower Manhattan, somebody would have had to climb into the cockloft by one of several stairways, entering by doors that should have been locked.

The cockloft, Chief Beier said, was a maze of catwalks and ceiling supports criss-crossed with ducts that vent fumes and heat from the stoves of fast-food outlets in the terminal, that support heating and air-conditioning systems and carry electrical wiring. In addition, the cockloft is full of struts and supports for the ceiling panels.

It was somewhere in this maze, hidden behind the ceiling, that the flames started.Thirty feet below, waiting for a ferry to take her to work at a McDonald's restaurant on Staten Island, Lora Carmona, 20 years old, who has been staying with friends on Governor's Island, smelled something peculiar.

"I thought they were burning something, the cooks over there, and pretty soon they started saying 'Everyone out of here!'," she recalled. She said there were 200 people in the terminal, though others said there were fewer than 100.

"We thought it was pizza burning," said Robin Rahman, who works at the Kwik Stop Deli in the terminal. But suddenly, she added, "We looked up and we saw it in the roof."

Flames seemed to be rolling under the ceiling, spreading rapidly, and billows of smoke were pouring out.

"Some people were shouting, 'Fire!' and all the people started running," said another man. Then, pieces of the ceiling began to fall in flames onto the concourse, and fear turned to panic.

A woman who gave her name only as Carmela said she was just walking up a ramp to enter the terminal, heading for Staten Island to visit her granddaugthter when she heard the cries.

"A policeman came screaming, 'Get off the ramp! Get off the ramp!' " she said. "There was terrible smoke, like Hiroshima with that mushroom cloud. It was all big black billowing smoke. Then the flames came. They started big. Masses of humanity were here.

The first firemen to arrive saw a pillar of smoke rising into the sky. "When we got here at 8:15, we went straight up on the roof," said a firefighter, Jim Esposito. "When we tried to pull off a panel to vent the smoke, we saw large flames beneath it. We had to evacuate right away."