You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FDNY and NYC Firehouses and Fire Companies - 2nd Section

- Thread starter mack

- Start date

365 JAY STREET FORMER FIREHOUSE

Brooklyn Fire Headquarters

By Dan Brenner

Posted on June 5, 2019

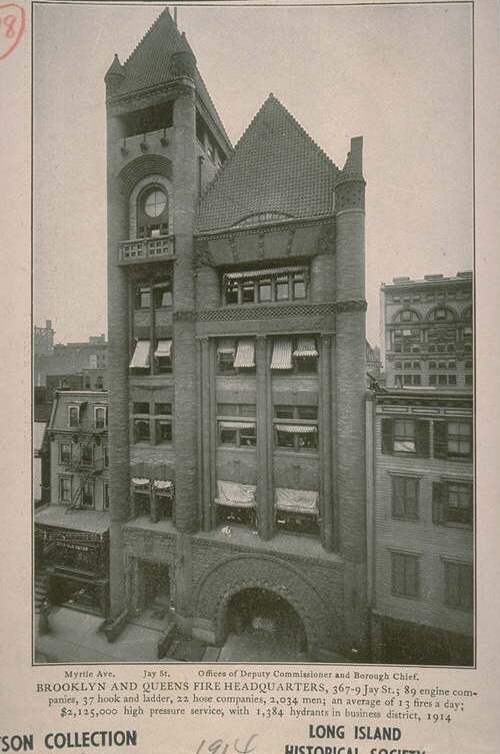

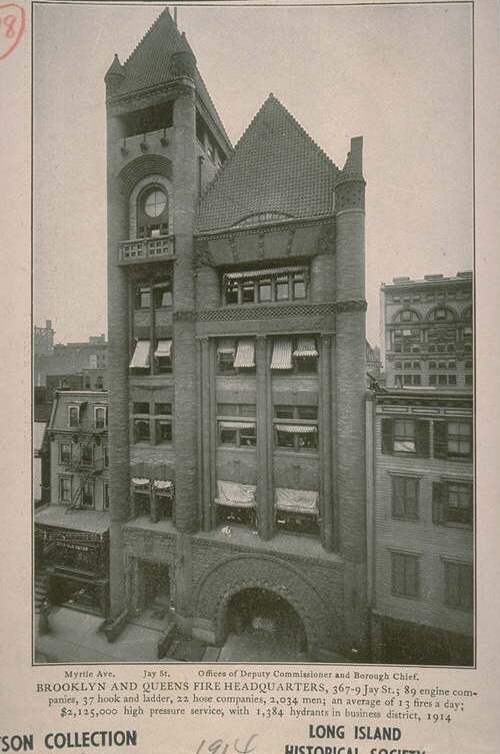

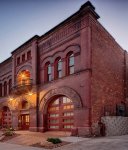

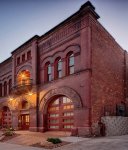

In 1892, the Brooklyn Fire Department opened its headquarters at 365-67 Jay Street, located between Myrtle Avenue and Willoughby Street in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights. The building was designed by renowned Richardsonian Romanesque Style (and later, Neoclassical) architect Frank Freeman, also known for such brilliant works as the Herman Behr Mansion in Brooklyn Heights, and the Eagle Warehouse in the DUMBO neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Six years after it’s opening, the Brooklyn Fire Department would be no more due to the consolidation of all five boroughs into the City of Greater New York on January 1, 1898. No longer being an independent city requiring its own fire department headquarters, Brooklyn’s 365-67 Jay Street station was absorbed into the newly incorporated Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY).

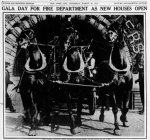

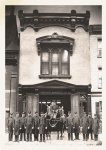

At the time the photograph above was taken, the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens had a total of 89 engine companies who employed 2,089 workers, with an average of thirteen fires daily. The Rescue 2 unit of the FDNY occupied the building on Jay Street in 1929 where they remained until 1946. The building continued to function as a working firehouse until the 1970s, when it was leased out to Brooklyn Polytechnic University for classroom space amidst severe state budgetary cuts in education at the time.

365-67 Jay Street was designated for landmark status in 1966 by the recently formed Landmark Preservation Commission of NYC and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. In 1987, the firehouse was converted into affordable housing apartments for local residents who were being displaced by construction for the newly-developed MetroTech Center, a sixteen-acre academic and industrial research park.

www.brooklynhistory.org

www.brooklynhistory.org

Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters

Brooklyn Fire Headquarters, c.1910

Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters is located in New York City

General information

Type Originally a fire station, now residential apartments

Architectural style Richardsonian Romanesque

Address 365-367 Jay Street

Brooklyn, New York City

Design and construction

Architect Frank Freeman

U.S. National Register of Historic Places

NYC Landmark

Coordinates 40°41′34″N 73°59′13″WCoordinates: 40°41′34″N 73°59′13″W

Built 1892

The Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters is a historic building located at 365-67 Jay Street near Willoughby Street in Downtown Brooklyn, New York City. Designed by Frank Freeman in the Richardsonian Romanesque Revival style and built in 1892 for the Brooklyn Fire Department, it was used as a fire station until the 1970s, after which it was converted into residential apartments. The building, described as "one of New York's best and most striking architectural compositions", was made a New York City landmark in 1966, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

Construction and use

Around 1890, the Brooklyn Fire Department began planning for the construction of a new fire headquarters with a tall lookout tower. A plot of land was eventually purchased for the purpose on Jay Street, adjacent to the quarters of Engine Company 17, for $15,000. At this point, a dispute arose as to the choice of architect. Fire Commissioner John Ennis favored a protégé of local Democratic Party leader Hugh "Boss" McLaughlin, but the city works commissioner, John P. Adams, preferred another firm. Eventually, a compromise candidate was selected—Frank Freeman, a leading exponent of the Richardsonian Romanesque style, who had recently completed the Thomas Jefferson Association Building for the Kings County Democrats.

The new building was completed in 1892, although the fire department did not occupy the building until March 1894. Though originally intended as the department's headquarters, it served in this role for only six years, when the City of Brooklyn was incorporated as a borough into the City of New York, after which the building became "simply, the most splendid neighborhood firehouse in Greater New York."

The building was retained as a firehouse by the New York City Fire Department until the 1970s, serving as the home of various units including Ladder 110 and 118, Engine 207, and from 1947 to 1971, Battalion 31. In the 1930s, it also served as the HQ of Searchlight 2, a unit which utilized a Packard sedan modified to carry searchlights, in an era before fire engines were fitted with their own searchlights. In 1966, the building was designated as a New York City landmark, and in 1972, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Subsequent use

The building in 2012

After the Fire Department vacated the premises, it was leased for a time by Polytechnic University. In 1987, the Board of Estimate proposed a conversion of the then-vacant building into 18 apartments for low-income and elderly people with the MetroTech Center. The plan was met with considerable resistance in some quarters. However, the conversion subsequently went ahead in 1989, partly on the grounds that continued use would prevent the building from falling into decay.

The Black United Fund of New York took over the building from the 1990s until 2005, when ownership returned to the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. However, the deterioration continued and, in 2006, the New York Times said that the building had a "musty, neglected air" and was in need of maintenance, with parts of its roofing having disintegrated.

In 2008, the Pratt Area Community Council received a budget allocation of $400,000 toward the renovation of the Jay Street firehouse. Nomad Architecture subsequently started a project to convert the building to residential use. he project began in spring 2011 and was completed in 2015.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Brooklyn Fire Headquarters

By Dan Brenner

Posted on June 5, 2019

In 1892, the Brooklyn Fire Department opened its headquarters at 365-67 Jay Street, located between Myrtle Avenue and Willoughby Street in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights. The building was designed by renowned Richardsonian Romanesque Style (and later, Neoclassical) architect Frank Freeman, also known for such brilliant works as the Herman Behr Mansion in Brooklyn Heights, and the Eagle Warehouse in the DUMBO neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Six years after it’s opening, the Brooklyn Fire Department would be no more due to the consolidation of all five boroughs into the City of Greater New York on January 1, 1898. No longer being an independent city requiring its own fire department headquarters, Brooklyn’s 365-67 Jay Street station was absorbed into the newly incorporated Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY).

At the time the photograph above was taken, the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens had a total of 89 engine companies who employed 2,089 workers, with an average of thirteen fires daily. The Rescue 2 unit of the FDNY occupied the building on Jay Street in 1929 where they remained until 1946. The building continued to function as a working firehouse until the 1970s, when it was leased out to Brooklyn Polytechnic University for classroom space amidst severe state budgetary cuts in education at the time.

365-67 Jay Street was designated for landmark status in 1966 by the recently formed Landmark Preservation Commission of NYC and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. In 1987, the firehouse was converted into affordable housing apartments for local residents who were being displaced by construction for the newly-developed MetroTech Center, a sixteen-acre academic and industrial research park.

Brooklyn Fire Headquarters - Center for Brooklyn History | Center for Brooklyn History

In 1892, the Brooklyn Fire Department opened its headquarters at 365-67 Jay Street...

Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters

Brooklyn Fire Headquarters, c.1910

Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters is located in New York City

General information

Type Originally a fire station, now residential apartments

Architectural style Richardsonian Romanesque

Address 365-367 Jay Street

Brooklyn, New York City

Design and construction

Architect Frank Freeman

U.S. National Register of Historic Places

NYC Landmark

Coordinates 40°41′34″N 73°59′13″WCoordinates: 40°41′34″N 73°59′13″W

Built 1892

The Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters is a historic building located at 365-67 Jay Street near Willoughby Street in Downtown Brooklyn, New York City. Designed by Frank Freeman in the Richardsonian Romanesque Revival style and built in 1892 for the Brooklyn Fire Department, it was used as a fire station until the 1970s, after which it was converted into residential apartments. The building, described as "one of New York's best and most striking architectural compositions", was made a New York City landmark in 1966, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

Construction and use

Around 1890, the Brooklyn Fire Department began planning for the construction of a new fire headquarters with a tall lookout tower. A plot of land was eventually purchased for the purpose on Jay Street, adjacent to the quarters of Engine Company 17, for $15,000. At this point, a dispute arose as to the choice of architect. Fire Commissioner John Ennis favored a protégé of local Democratic Party leader Hugh "Boss" McLaughlin, but the city works commissioner, John P. Adams, preferred another firm. Eventually, a compromise candidate was selected—Frank Freeman, a leading exponent of the Richardsonian Romanesque style, who had recently completed the Thomas Jefferson Association Building for the Kings County Democrats.

The new building was completed in 1892, although the fire department did not occupy the building until March 1894. Though originally intended as the department's headquarters, it served in this role for only six years, when the City of Brooklyn was incorporated as a borough into the City of New York, after which the building became "simply, the most splendid neighborhood firehouse in Greater New York."

The building was retained as a firehouse by the New York City Fire Department until the 1970s, serving as the home of various units including Ladder 110 and 118, Engine 207, and from 1947 to 1971, Battalion 31. In the 1930s, it also served as the HQ of Searchlight 2, a unit which utilized a Packard sedan modified to carry searchlights, in an era before fire engines were fitted with their own searchlights. In 1966, the building was designated as a New York City landmark, and in 1972, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Subsequent use

The building in 2012

After the Fire Department vacated the premises, it was leased for a time by Polytechnic University. In 1987, the Board of Estimate proposed a conversion of the then-vacant building into 18 apartments for low-income and elderly people with the MetroTech Center. The plan was met with considerable resistance in some quarters. However, the conversion subsequently went ahead in 1989, partly on the grounds that continued use would prevent the building from falling into decay.

The Black United Fund of New York took over the building from the 1990s until 2005, when ownership returned to the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. However, the deterioration continued and, in 2006, the New York Times said that the building had a "musty, neglected air" and was in need of maintenance, with parts of its roofing having disintegrated.

In 2008, the Pratt Area Community Council received a budget allocation of $400,000 toward the renovation of the Jay Street firehouse. Nomad Architecture subsequently started a project to convert the building to residential use. he project began in spring 2011 and was completed in 2015.

Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Last edited:

Future New York

From Future New YorkRare Gems: 12 Firehouses turned residences throughout NYC

www.cityrealty.com

www.cityrealty.com

From Future New YorkRare Gems: 12 Firehouses turned residences throughout NYC

Rare Gems: 12 Firehouses turned residences throughout NYC

160 Chambers Street, Tribeca : The COVID-19 pandemic is the undoubtedly the first experience of its kind for many New Yorkers. However, from the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire of

8 Repurposed Fire Stations in NYC

8 Repurposed Fire Stations in NYC - Untapped New York

Eight fire stations in NYC that have been converted into great uses, including a television station, the NYC Fire Museum, a spa and the home of Anderson Cooper

Former firehouse in New York City. Circa 1900. $21,800,000

Former firehouse in New York City. Circa 1900. $21,800,000 - The Old House Life

This former firehouse has been transformed into a private residence. And boy, that price tag! This was built in 1900. It is located in New York City, New York. It is situated in the heart of West Village. The bottom floor has been transformed into a four car garage. Three bedrooms, six...

theoldhouselife.com

theoldhouselife.com

Rent Andy Warhol’s former firehouse home in NYC

Andy Warhol’s converted firehouse home is up for rent in New York’s Chelsea for $33,000.

Spanning 4,600 sq ft, the duplex – on the market via Elissa Slan of Douglas Elliman – sits within the Old Chelsea Firehouse, built around 1865. Though its stint as a firehouse was short (by 1875 it was already given over to domestic use), it has a long creative legacy.

In the early 1900s, John Yeats lived in the New York property and 1930s dancer Franziska Marie Boa set up a studio on the building’s second floor. Her roommates? Andy Warhol and Philip Pearlstein, who lived there until they were evicted.

Visitors step through the engine-red doors at 323 West 21st Street into a private garage. From here, the duplex’s entry passage is laid with original cobblestone floors, and a decorative period fireplace.

Courtesy of Douglas Elliman

The converted firehouse has an enormous family living space with floor-to-ceiling windows that open onto a double-height winter garden. A carved staircase leads up to bedrooms on the upper floor, as well as a library and study.

You can rent the four bedroom New York apartment from 1 April.

thespaces.com

thespaces.com

Andy Warhol’s converted firehouse home is up for rent in New York’s Chelsea for $33,000.

Spanning 4,600 sq ft, the duplex – on the market via Elissa Slan of Douglas Elliman – sits within the Old Chelsea Firehouse, built around 1865. Though its stint as a firehouse was short (by 1875 it was already given over to domestic use), it has a long creative legacy.

In the early 1900s, John Yeats lived in the New York property and 1930s dancer Franziska Marie Boa set up a studio on the building’s second floor. Her roommates? Andy Warhol and Philip Pearlstein, who lived there until they were evicted.

Visitors step through the engine-red doors at 323 West 21st Street into a private garage. From here, the duplex’s entry passage is laid with original cobblestone floors, and a decorative period fireplace.

Courtesy of Douglas Elliman

The converted firehouse has an enormous family living space with floor-to-ceiling windows that open onto a double-height winter garden. A carved staircase leads up to bedrooms on the upper floor, as well as a library and study.

You can rent the four bedroom New York apartment from 1 April.

Rent a converted firehouse in NYC once home to Andy Warhol

Converted firehouse, home to artists Andy Warhol and Philip Pearlstein in 1949, is now up for rent in New York’s Chelsea – at $33,000 per month

thespaces.com

thespaces.com

Attachments

-

house-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol--100x100.jpg4.7 KB · Views: 3

house-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol--100x100.jpg4.7 KB · Views: 3 -

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-2-100x100.jpg3.7 KB · Views: 3

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-2-100x100.jpg3.7 KB · Views: 3 -

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-4-100x100.jpg4.3 KB · Views: 2

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-4-100x100.jpg4.3 KB · Views: 2 -

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-5-100x100.jpg4.3 KB · Views: 2

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-5-100x100.jpg4.3 KB · Views: 2 -

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-6-100x100.jpg5.6 KB · Views: 2

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-6-100x100.jpg5.6 KB · Views: 2 -

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-7-100x100.jpg4.7 KB · Views: 3

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-7-100x100.jpg4.7 KB · Views: 3 -

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-9-100x100.jpg4.9 KB · Views: 3

ouse-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-9-100x100.jpg4.9 KB · Views: 3 -

use-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-10-100x100.jpg5.3 KB · Views: 3

use-for-rent-former-home-of-Andy-Warhol-10-100x100.jpg5.3 KB · Views: 3

$5.5M converted firehouse could be Long Island City’s most expensive sale

POSTED ON THU, MAY 17, 2018BY MICHELLE COHEN

VIEW PHOTO IN GALLERY

A listing broker for this 1848 former local firehouse told the Wall Street Journal that its $5.5 million asking price was “aspirational,” but the neighborhood certainly has changed since its owner purchased the three-story, 3,500 square-foot converted townhouse in 1981 for $115,000. Long Island City turned fancy and this Federal-style firehouse got an architect-led overhaul that gave it three bedrooms, a 17-foot vaulted ceiling, a home office/library, a garden, a terrace, a garage, an elevator, and a sliding glass wall.

Back when she purchased the quaint red-brick building in the Dutch Kills section of Long Island City, neighbors told the owner it was worth even less than the $100K she paid for it; the broker called it a “white elephant.” The ensuing decades saw the area become a favorite with young professionals for its proximity to Manhattan, its cool industrial vibe, and great city views. If the house sells for its current ask, it will set a new neighborhood record, currently held by the $4 million sale of a three-story townhouse in Hunters Point in 2015.

The building is currently configured as a two-family dwelling with a spacious garden apartment on the ground floor ready to generate market rate income. Or you can keep the ground floor space with an adjacent 700-square-foot garden courtyard as a gorgeous work or living space. Mixed-use zoning means you can run a business on the downstairs level; The building also comes with nearly 3,800 additional square feet of development rights.

The second floor is where you’ll find the dining area with vaulted 17-foot ceilings, a Danish-designed wood-burning stove, and a chef’s kitchen with two stainless Dacor ovens.

A generous master suite boasts a home office or library, a large walk-in closet and a master bath with radiant heat limestone floors and Toto toilets. A white marble and limestone guest bathroom sits off this floor’s hallway.

Up on the third floor is a third bedroom and an architect-designed living space with sliding glass walls that open onto a terrace for indoor/outdoor living. The interior living space also offers a marble wet-bar, a limestone wood-burning fireplace, dishwasher, and refrigerator. A limestone terrace off the living room includes a gas grill and built-in hot tub and beautiful views of LIC and Manhattan.

The building’s basement level offers additional storage, more work space, a full-sized laundry area and building mechanicals. It is accessible by elevator or stairs.

www.6sqft.com

www.6sqft.com

POSTED ON THU, MAY 17, 2018BY MICHELLE COHEN

VIEW PHOTO IN GALLERY

A listing broker for this 1848 former local firehouse told the Wall Street Journal that its $5.5 million asking price was “aspirational,” but the neighborhood certainly has changed since its owner purchased the three-story, 3,500 square-foot converted townhouse in 1981 for $115,000. Long Island City turned fancy and this Federal-style firehouse got an architect-led overhaul that gave it three bedrooms, a 17-foot vaulted ceiling, a home office/library, a garden, a terrace, a garage, an elevator, and a sliding glass wall.

Back when she purchased the quaint red-brick building in the Dutch Kills section of Long Island City, neighbors told the owner it was worth even less than the $100K she paid for it; the broker called it a “white elephant.” The ensuing decades saw the area become a favorite with young professionals for its proximity to Manhattan, its cool industrial vibe, and great city views. If the house sells for its current ask, it will set a new neighborhood record, currently held by the $4 million sale of a three-story townhouse in Hunters Point in 2015.

The building is currently configured as a two-family dwelling with a spacious garden apartment on the ground floor ready to generate market rate income. Or you can keep the ground floor space with an adjacent 700-square-foot garden courtyard as a gorgeous work or living space. Mixed-use zoning means you can run a business on the downstairs level; The building also comes with nearly 3,800 additional square feet of development rights.

The second floor is where you’ll find the dining area with vaulted 17-foot ceilings, a Danish-designed wood-burning stove, and a chef’s kitchen with two stainless Dacor ovens.

A generous master suite boasts a home office or library, a large walk-in closet and a master bath with radiant heat limestone floors and Toto toilets. A white marble and limestone guest bathroom sits off this floor’s hallway.

Up on the third floor is a third bedroom and an architect-designed living space with sliding glass walls that open onto a terrace for indoor/outdoor living. The interior living space also offers a marble wet-bar, a limestone wood-burning fireplace, dishwasher, and refrigerator. A limestone terrace off the living room includes a gas grill and built-in hot tub and beautiful views of LIC and Manhattan.

The building’s basement level offers additional storage, more work space, a full-sized laundry area and building mechanicals. It is accessible by elevator or stairs.

$5.5M converted firehouse could be Long Island City’s most expensive sale | 6sqft

A listing broker for this 1848 former local firehouse told the Wall Street Journal that its $5.5 million asking price was “aspirational,” but the neighborhood certainly has changed since its owner purchased the three-story, 3,500 square-foot converted townhouse in 1981 for $100,000.

This rental's on fire: Live in a converted firehouse in Williamsburg

JULY 12, 2016 - 9:59AM

BY ALANNA SCHUBACH

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

SHARE

SHARE

TWEET

TWEET

COMMENT

COMMENT

PRINT

PRINT

MORE

MORE

It can't be easy to maintain an edge over your neighbors in always on-trend Williamsburg, but renting this 5,000-square-foot property, listed by Citi Habitats for $15,000/month, should help. 246 Frost Street is a two-story, converted 19th-century firehouse, and its unique history also means rare and enticing perks. The building is zoned for both residential and commercial use, for instance, which makes it a great spot for artists or musicians who want to use the ground floor for performance or gallery space. And as with carriage houses, there's an in-home garage where you can park your ride, which you'll likely want to use once the nearby L train shuts down.

The second floor—large enough for separate living and dining areas—makes a striking impression, with its high ceilings, dark slate flooring, exposed brick, large windows, and skylight that helps illuminate the space. You'll also find two working fireplaces and built-in cabinetry; there's a bathroom and closet on this level as well.

The kitchen is outfitted for serious home cooks, with custom cabinetry and stainless steel appliances. You can make a feast on the double stoves, and the long granite counters offer tons of room for prep.

The kitchen opens onto a private roof deck with a Jacuzzi; room for a grill and seating means the space is primed for summer barbecues. On the ground floor, the parking garage makes it a breeze to pull right into your home and unload the groceries.

The floorplan reveals a family room past the garage, followed by the master bedroom and home office space; there's also a sleeping loft above the living area. Since these aren't pictured in the listing, prospective renters should do their due diligence before making a move. That said, a resourceful, creative type would have a lot to work with here, and would likely draw some inspiration from their stylish and historic surroundings.

www.brickunderground.com

www.brickunderground.com

JULY 12, 2016 - 9:59AM

BY ALANNA SCHUBACH

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

It can't be easy to maintain an edge over your neighbors in always on-trend Williamsburg, but renting this 5,000-square-foot property, listed by Citi Habitats for $15,000/month, should help. 246 Frost Street is a two-story, converted 19th-century firehouse, and its unique history also means rare and enticing perks. The building is zoned for both residential and commercial use, for instance, which makes it a great spot for artists or musicians who want to use the ground floor for performance or gallery space. And as with carriage houses, there's an in-home garage where you can park your ride, which you'll likely want to use once the nearby L train shuts down.

The second floor—large enough for separate living and dining areas—makes a striking impression, with its high ceilings, dark slate flooring, exposed brick, large windows, and skylight that helps illuminate the space. You'll also find two working fireplaces and built-in cabinetry; there's a bathroom and closet on this level as well.

The kitchen is outfitted for serious home cooks, with custom cabinetry and stainless steel appliances. You can make a feast on the double stoves, and the long granite counters offer tons of room for prep.

The kitchen opens onto a private roof deck with a Jacuzzi; room for a grill and seating means the space is primed for summer barbecues. On the ground floor, the parking garage makes it a breeze to pull right into your home and unload the groceries.

The floorplan reveals a family room past the garage, followed by the master bedroom and home office space; there's also a sleeping loft above the living area. Since these aren't pictured in the listing, prospective renters should do their due diligence before making a move. That said, a resourceful, creative type would have a lot to work with here, and would likely draw some inspiration from their stylish and historic surroundings.

This rental's on fire: Live in a converted firehouse in Williamsburg

A historic firehouse has been updated for artist-friendly living.

Village Firehouse Architecture is HOT

POSTED AUGUST 13, 2019

BY DYLAN GARCIA

The city might feel like its been on fire this record-breaking summer, but there have been times in the past when it has been. In the 1970s the Bronx was burning and Lower East Side was also suffering from fires and abandoned buildings. Before that, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire became one of the worst workplace tragedies to ever occur. In the late 19th century, the booming population of the city brought with it a great need for fire protection. During that time, some beautiful firehouses were built and served a crucial function for the city, both before and after the creation of the Fire Department of New York (FDNY).

Today we’re going to tour some of these beautiful historic buildings in Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo.

Empire Hose Company No. 40, 70 Barrow Street

One of the oldest firehouses in New York, this structure was built in 1852, before there even was an organized Fire Department of New York. In 1865, the city created the Metropolitan Fire Department (MFD) which managed all of the city’s fire responses. Before that, firehouses were operated by volunteers who formed groups and petitioned the city to build them a firehouse and provide them with the materials. Most firehouse members were blue-collar workers, volunteering any extra time they had. At 70 Barrow street, a volunteer group called Empire Hose Company No. 40 had around 30 members until it was disbanded after the act of 1865. The original firehouse doorway has been bricked over partially, but its classic look is still legible.

Our friend Tom Miller at the Daytonian in Manhattan blog noted “The carved, faceted keystones at street level and the third floor were an added touch of sophistication to the handsome four-story structure. Unusually tall windows, deft brickwork, and a deeply-overhanging cornice set the firehouse apart from the norm” (see all of Tom’s fascinating blog posts about buildings within the Greenwich Village Historic District, including this one, on our Greenwich Village Historic District 1969-2019 Map and Tour at www.gvshp.org/GVHD50tour).

Fire Patrol No. 2, 31 Great Jones Street

Nos 31 (left) and 33 Great Jones Street. Image from Daytonian in Manhattan

Nos 31 (left) and 33 Great Jones Street. Image from Daytonian in Manhattan

Built in 1871 and designed by architect W.E. Waring, this firehouse… wasn’t exactly a firehouse. In 1835 the Association of Fire Insurance Companies formed a group called the New York Fire Patrol. This group wasn’t responsible for extinguishing fires, but rather for salvaging valuables and minimizing the damage to the building itself once the fire had been fought. The Patrol existed before the creation of the unified fire department and continued to operate after its formation, so its functions have changed over the years. This became their Fire Patrol House No. 2.

Funnily enough, the property next door at 33 Great Jones was purchased by Willcox & Gibbs Sewing Machine Company and their designer, Charles Wright, created an exact replica of the firehouse building next door. Fire Patrol No. 2 left No. 31 in 1907 for a new location (see 84 West 3rd Street, below), and now an upscale restaurant by the name of Vic’s occupies the ground floor.

Engine Co. No. 33, 44 Great Jones

A little further down Great Jones Street sits a truly remarkable firehouse. Since 1898, Engine Co. 33 has occupied this building, designed by famed New York City architects Ernest Flagg and W.B. Chambers. The stunning French Beaux-Arts styled facade immediately grabs the attention of passersby, which still features the classic red doors, central windows, and grand archways characteristic of firehouses. The building’s landmark designation report, written in 1968, says: “This utilitarian building has a flamboyance that is particularly appropriate to the function of the hazardous profession engaged in by its occupants.”

A Village Preservation blog post notes that it could be considered double-landmarked since it was first an individual landmark, then later became a part of the NoHo Historic District Extension (read the NoHo Historic District Designation Report here). With its exceptional beauty, 44 Great Jones clearly deserves double recognition (and preservation).

Fire Patrol No. 2, 84 West 3rd Street

This is the location that the Fire Patrol moved to when it vacated 31 Great Jones Street. This new location is the 5th and last built for the Patrol. Constructed in 1907 and designed by architect Franklin Baylies, it has an immediately recognizable classic-firehouse look. The Patrol stayed in that building for almost a hundred years, saving damaged goods and chugging along as the only insurance supported salvage company. The Fire Patrol was suddenly disbanded in 2006 and the building put up for sale, sparking Village Preservation to seek to landmark it as quickly as possible. In 2010 news anchor Anderson Cooper bought the building, but lucky for us, he kept the character of it intact while renovating it to fit the needs of a private residence (for a peek at what it looked like pre-renovation, check out our collection of images of the building and its interior from our historic image archive). Village Preservation secured landmark status for the building in 2013 as part of the South Village Historic District. See more about this here.

Columbia Hook and Ladder Co., 102 Charles Street

Another pre-Metropolitan Fire Department company, the Columbia Hook and Ladder Company occupied this firehouse and volunteered their time to protect the neighborhood. The Building was originally constructed as a home for accountant Samuel D. Chase in 1854. The city purchased the home just one year later and converted it to the Hook and Ladder Company. When the city switched to its paid, unified system, the Fire Department took over the building. Unusually, the Department moved out of the building in the 1960s when a flea infestation from some stray cats became unmanageable. Fleas can be more powerful than even fires! Now, the building is home to a street-level storefront with residences above.

Engine Company 18, 132 West 10th Street

This quintessential firehouse was designed by the great New York Firehouse architect Napoleon Lebrun. From the time he was made the lead architect in 1879 for the Fire Department, Lebrun designed a total of 42 firehouses as well as some other fire department structures throughout New York City, mostly in Manhattan (which of course was New York City until 1898). Engine Company 18 was built in 1892 when the city’s population rapidly increasing and new firehouses were direly needed. This company on West 10th Street was one of the many that responded to the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911, and to the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2001. The firehouse still stands in the heart of the Greenwich Village Historic District. Read on for more information on the architect Napoleon Lebrun.

Former Engine Co. 30, Now the New York City Fire Museum, 278 Spring Street

Just on the edge of Village Preservation’s neighborhoods, this historic firehouse is especially unique because of its size. When it was being built in 1904, the New York Times said it would become “one of the largest fire engine houses in the city.” Designed by architect Edward P. Casey, the iconic large rusticated limestone base supports a beautiful brick facade and elegant windows. In 1987 the city decided the location was no longer needed as an active firehouse. When considering what to do with the building, the Department decided that, because of its size, it would be a perfect home for their museum, then located at 100 Duane Street, which was growing too large for its space. And so they relocated the New York City Fire Museum to Spring Street and opened on July 6th of that year.

Perry Hose Company, 48 Horatio Street

Another old-timer of the collection, the volunteer-based Perry Hose Company fought off fires in the time before the creation of the Metropolitan Fire Department. The company’s name honors Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who commanded several ships in the Mexican-American War and the War of 1812, and whose remains were, for a while at least, interred in the graveyard of St. Mark’s in the Bowery Church. The present building dates to 1856, having replaced the Company’s original firehouse which had been located on the site. The firehouse’s services didn’t continue after the 1865 act, but the colonial character and distinct firetruck archway were preserved in the building’s conversion to a private residence.

Former Engine House No. 28, 604 East 11th Street

This three-story firehouse was built in 1879 and designed by Napoleon LeBrun as Engine House No. 28 — one of LeBrun’s first firehouses after becoming the FDNY’s lead architect. The building utilizes a simple Neo-classical cornice and sandstone trim to ornament the facade. It has projections at the ends, acting like pilasters joining the ornamentation for the ground floor up to the brackets on the cornice. The ground floor still retains its original configuration, however, part of the large center door has been infilled with glass block. The building was converted to three floor-through residences, which in 2012 were asking $22,000/month in rent. More about the building can be found on our East Village Building Blocks website here.

Engine Company No. 5, 340 East 14th Street

Unlike the nearly-identical 604 East 11th Street just a few blocks away, this firehouse still functions as an FDNY fire company. Like its near-twin, it was designed by architect Napoleon LeBrun, completed just a year later in 1880, making it also one of LeBrun’s earliest FDNY creations, in which he first created the template for these firehouse designs. In 1889 a new steel floor was installed and the rear elevation was extended, but other than that, the building looks more or less as it did one hundred forty years ago when it began fighting fires. Read and see more about the building on our East Village Building Blocks website here.

Former Engine 24, 78 Morton Street

Built in 1864 as the ‘Howard Engine Company No. 34,” known affectionately as “Red Rover,” this engine company was first organized in 1807 as a volunteer fire-fighting company. It was eventually absorbed by the FDNY and became Engine No. 24. In 1975 in the middle of the city’s financial crisis it was decommissioned, and lay empty for many years. Much of the facade’s ornament was stripped away, but ealier this decade the elaborate detailing over and around the building’s windows were restored. The building now contains a residence.

Hook and Ladder Company No. 3, 108 East 13th Street

Built in 1928, this is the relative newbie in this list, and along with the 1907 former Engine Company No. 30 at 278 Spring Street, the only entry not from the 19th century. Unlike it’s Spring Street counterpart, however Ladder Co. No. 3 very much still functions out of this building just east of 4th Avenue. And it has a storied history; as the plaques on its exterior attest, it lost most of its men responding to the September 11th attacks, making it one of the hardest-hit firehouses in the entire city. Perhaps somewhat sadly, the company was first organized on September 11, 1865, originally located just west of here on 13th Street. On a less somber note, another plaque on the firehouses facade from its opening in 1929 proudly proclaims that it was commissioned by then-Mayor James J. (“Gentleman Jim”) Walker, one of New York’s most colorful mayors. Read and see more about the building on our East Village Building Blocks website here.

Oceanus Engine Co. No. 11/FDNY Engine Co. 13/Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse, 99 Wooster Street

The former Engine Co. 13 at 99 Wooster has had quite an interesting history. Another dating back to the pre-MFD, it was originally the volunteer Oceanus Engine Co. 11. When the Firehouses unified, the previously mentioned Lebrun & Sons made renovations, and in 1881 gave the building its classic Lebrun firehouse look which it retains to today.

Fire response wasn’t the only community service to be offered out of this space, however. From April 1971 until October 1974, the Gay Activist Alliance operated its headquarters here. In 2014, Village Preservation proposed this and three other sites connected to LGBT history for landmark designation, including the Stonewall Inn and the LGBT Community Center, all three of which have now been landmarked. Regarding 99 Wooster’s time in the early 1970s as the GAA Firehouse, a recent Village Preservation blog notes, “During this era SoHo was a lively hub of creative energy and activity. Loft living in former commercial buildings by certified artists was legalized by the Board of Estimate in January 1971 and there were a growing number of commercial art galleries, cooperative galleries, and alternative (non-profit) spaces.” The GAA began looking for a “community center” towards the end of 1970 and leased 99 Wooster Street as their community center. Now, the former firehouse and home of important LGBT cultural history is a storefront and single-family home.

Jefferson Market Fire Lookout

Jefferson Market Library. NYPL

Jefferson Market Library. NYPL

While the Jefferson Market Library is known for its beautiful architecture and history as a courthouse, less well-known is that the clocktower also served as a fire watchtower for many years in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Constructed in 1877, it was one of the tallest structures in the city at the time. At 172 feet tall, it was an ideal lookout. The watchman would ring the bells in the tower to alert volunteer firefighters. The tower was used until 1945 when the building became a police academy. It became the library we know today in 1967.

The telltale 19th-century Firehouse architecture – the arches, the red doors, the sets of windows – are easily recognizable, whether the building still functions as an FDNY firehouse, or has become a museum, a home, or a store. The reuse of these buildings highlights the layered uses of protected buildings in the Village, full of histories of literal lifesaving.

www.villagepreservation.org

www.villagepreservation.org

POSTED AUGUST 13, 2019

BY DYLAN GARCIA

The city might feel like its been on fire this record-breaking summer, but there have been times in the past when it has been. In the 1970s the Bronx was burning and Lower East Side was also suffering from fires and abandoned buildings. Before that, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire became one of the worst workplace tragedies to ever occur. In the late 19th century, the booming population of the city brought with it a great need for fire protection. During that time, some beautiful firehouses were built and served a crucial function for the city, both before and after the creation of the Fire Department of New York (FDNY).

Today we’re going to tour some of these beautiful historic buildings in Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo.

Empire Hose Company No. 40, 70 Barrow Street

One of the oldest firehouses in New York, this structure was built in 1852, before there even was an organized Fire Department of New York. In 1865, the city created the Metropolitan Fire Department (MFD) which managed all of the city’s fire responses. Before that, firehouses were operated by volunteers who formed groups and petitioned the city to build them a firehouse and provide them with the materials. Most firehouse members were blue-collar workers, volunteering any extra time they had. At 70 Barrow street, a volunteer group called Empire Hose Company No. 40 had around 30 members until it was disbanded after the act of 1865. The original firehouse doorway has been bricked over partially, but its classic look is still legible.

Our friend Tom Miller at the Daytonian in Manhattan blog noted “The carved, faceted keystones at street level and the third floor were an added touch of sophistication to the handsome four-story structure. Unusually tall windows, deft brickwork, and a deeply-overhanging cornice set the firehouse apart from the norm” (see all of Tom’s fascinating blog posts about buildings within the Greenwich Village Historic District, including this one, on our Greenwich Village Historic District 1969-2019 Map and Tour at www.gvshp.org/GVHD50tour).

Fire Patrol No. 2, 31 Great Jones Street

Nos 31 (left) and 33 Great Jones Street. Image from Daytonian in Manhattan

Nos 31 (left) and 33 Great Jones Street. Image from Daytonian in ManhattanBuilt in 1871 and designed by architect W.E. Waring, this firehouse… wasn’t exactly a firehouse. In 1835 the Association of Fire Insurance Companies formed a group called the New York Fire Patrol. This group wasn’t responsible for extinguishing fires, but rather for salvaging valuables and minimizing the damage to the building itself once the fire had been fought. The Patrol existed before the creation of the unified fire department and continued to operate after its formation, so its functions have changed over the years. This became their Fire Patrol House No. 2.

Funnily enough, the property next door at 33 Great Jones was purchased by Willcox & Gibbs Sewing Machine Company and their designer, Charles Wright, created an exact replica of the firehouse building next door. Fire Patrol No. 2 left No. 31 in 1907 for a new location (see 84 West 3rd Street, below), and now an upscale restaurant by the name of Vic’s occupies the ground floor.

Engine Co. No. 33, 44 Great Jones

A little further down Great Jones Street sits a truly remarkable firehouse. Since 1898, Engine Co. 33 has occupied this building, designed by famed New York City architects Ernest Flagg and W.B. Chambers. The stunning French Beaux-Arts styled facade immediately grabs the attention of passersby, which still features the classic red doors, central windows, and grand archways characteristic of firehouses. The building’s landmark designation report, written in 1968, says: “This utilitarian building has a flamboyance that is particularly appropriate to the function of the hazardous profession engaged in by its occupants.”

A Village Preservation blog post notes that it could be considered double-landmarked since it was first an individual landmark, then later became a part of the NoHo Historic District Extension (read the NoHo Historic District Designation Report here). With its exceptional beauty, 44 Great Jones clearly deserves double recognition (and preservation).

Fire Patrol No. 2, 84 West 3rd Street

This is the location that the Fire Patrol moved to when it vacated 31 Great Jones Street. This new location is the 5th and last built for the Patrol. Constructed in 1907 and designed by architect Franklin Baylies, it has an immediately recognizable classic-firehouse look. The Patrol stayed in that building for almost a hundred years, saving damaged goods and chugging along as the only insurance supported salvage company. The Fire Patrol was suddenly disbanded in 2006 and the building put up for sale, sparking Village Preservation to seek to landmark it as quickly as possible. In 2010 news anchor Anderson Cooper bought the building, but lucky for us, he kept the character of it intact while renovating it to fit the needs of a private residence (for a peek at what it looked like pre-renovation, check out our collection of images of the building and its interior from our historic image archive). Village Preservation secured landmark status for the building in 2013 as part of the South Village Historic District. See more about this here.

Columbia Hook and Ladder Co., 102 Charles Street

Another pre-Metropolitan Fire Department company, the Columbia Hook and Ladder Company occupied this firehouse and volunteered their time to protect the neighborhood. The Building was originally constructed as a home for accountant Samuel D. Chase in 1854. The city purchased the home just one year later and converted it to the Hook and Ladder Company. When the city switched to its paid, unified system, the Fire Department took over the building. Unusually, the Department moved out of the building in the 1960s when a flea infestation from some stray cats became unmanageable. Fleas can be more powerful than even fires! Now, the building is home to a street-level storefront with residences above.

Engine Company 18, 132 West 10th Street

This quintessential firehouse was designed by the great New York Firehouse architect Napoleon Lebrun. From the time he was made the lead architect in 1879 for the Fire Department, Lebrun designed a total of 42 firehouses as well as some other fire department structures throughout New York City, mostly in Manhattan (which of course was New York City until 1898). Engine Company 18 was built in 1892 when the city’s population rapidly increasing and new firehouses were direly needed. This company on West 10th Street was one of the many that responded to the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911, and to the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2001. The firehouse still stands in the heart of the Greenwich Village Historic District. Read on for more information on the architect Napoleon Lebrun.

Former Engine Co. 30, Now the New York City Fire Museum, 278 Spring Street

Just on the edge of Village Preservation’s neighborhoods, this historic firehouse is especially unique because of its size. When it was being built in 1904, the New York Times said it would become “one of the largest fire engine houses in the city.” Designed by architect Edward P. Casey, the iconic large rusticated limestone base supports a beautiful brick facade and elegant windows. In 1987 the city decided the location was no longer needed as an active firehouse. When considering what to do with the building, the Department decided that, because of its size, it would be a perfect home for their museum, then located at 100 Duane Street, which was growing too large for its space. And so they relocated the New York City Fire Museum to Spring Street and opened on July 6th of that year.

Perry Hose Company, 48 Horatio Street

Another old-timer of the collection, the volunteer-based Perry Hose Company fought off fires in the time before the creation of the Metropolitan Fire Department. The company’s name honors Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who commanded several ships in the Mexican-American War and the War of 1812, and whose remains were, for a while at least, interred in the graveyard of St. Mark’s in the Bowery Church. The present building dates to 1856, having replaced the Company’s original firehouse which had been located on the site. The firehouse’s services didn’t continue after the 1865 act, but the colonial character and distinct firetruck archway were preserved in the building’s conversion to a private residence.

Former Engine House No. 28, 604 East 11th Street

This three-story firehouse was built in 1879 and designed by Napoleon LeBrun as Engine House No. 28 — one of LeBrun’s first firehouses after becoming the FDNY’s lead architect. The building utilizes a simple Neo-classical cornice and sandstone trim to ornament the facade. It has projections at the ends, acting like pilasters joining the ornamentation for the ground floor up to the brackets on the cornice. The ground floor still retains its original configuration, however, part of the large center door has been infilled with glass block. The building was converted to three floor-through residences, which in 2012 were asking $22,000/month in rent. More about the building can be found on our East Village Building Blocks website here.

Engine Company No. 5, 340 East 14th Street

Unlike the nearly-identical 604 East 11th Street just a few blocks away, this firehouse still functions as an FDNY fire company. Like its near-twin, it was designed by architect Napoleon LeBrun, completed just a year later in 1880, making it also one of LeBrun’s earliest FDNY creations, in which he first created the template for these firehouse designs. In 1889 a new steel floor was installed and the rear elevation was extended, but other than that, the building looks more or less as it did one hundred forty years ago when it began fighting fires. Read and see more about the building on our East Village Building Blocks website here.

Former Engine 24, 78 Morton Street

Built in 1864 as the ‘Howard Engine Company No. 34,” known affectionately as “Red Rover,” this engine company was first organized in 1807 as a volunteer fire-fighting company. It was eventually absorbed by the FDNY and became Engine No. 24. In 1975 in the middle of the city’s financial crisis it was decommissioned, and lay empty for many years. Much of the facade’s ornament was stripped away, but ealier this decade the elaborate detailing over and around the building’s windows were restored. The building now contains a residence.

Hook and Ladder Company No. 3, 108 East 13th Street

Built in 1928, this is the relative newbie in this list, and along with the 1907 former Engine Company No. 30 at 278 Spring Street, the only entry not from the 19th century. Unlike it’s Spring Street counterpart, however Ladder Co. No. 3 very much still functions out of this building just east of 4th Avenue. And it has a storied history; as the plaques on its exterior attest, it lost most of its men responding to the September 11th attacks, making it one of the hardest-hit firehouses in the entire city. Perhaps somewhat sadly, the company was first organized on September 11, 1865, originally located just west of here on 13th Street. On a less somber note, another plaque on the firehouses facade from its opening in 1929 proudly proclaims that it was commissioned by then-Mayor James J. (“Gentleman Jim”) Walker, one of New York’s most colorful mayors. Read and see more about the building on our East Village Building Blocks website here.

Oceanus Engine Co. No. 11/FDNY Engine Co. 13/Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse, 99 Wooster Street

The former Engine Co. 13 at 99 Wooster has had quite an interesting history. Another dating back to the pre-MFD, it was originally the volunteer Oceanus Engine Co. 11. When the Firehouses unified, the previously mentioned Lebrun & Sons made renovations, and in 1881 gave the building its classic Lebrun firehouse look which it retains to today.

Fire response wasn’t the only community service to be offered out of this space, however. From April 1971 until October 1974, the Gay Activist Alliance operated its headquarters here. In 2014, Village Preservation proposed this and three other sites connected to LGBT history for landmark designation, including the Stonewall Inn and the LGBT Community Center, all three of which have now been landmarked. Regarding 99 Wooster’s time in the early 1970s as the GAA Firehouse, a recent Village Preservation blog notes, “During this era SoHo was a lively hub of creative energy and activity. Loft living in former commercial buildings by certified artists was legalized by the Board of Estimate in January 1971 and there were a growing number of commercial art galleries, cooperative galleries, and alternative (non-profit) spaces.” The GAA began looking for a “community center” towards the end of 1970 and leased 99 Wooster Street as their community center. Now, the former firehouse and home of important LGBT cultural history is a storefront and single-family home.

Jefferson Market Fire Lookout

Jefferson Market Library. NYPL

Jefferson Market Library. NYPLWhile the Jefferson Market Library is known for its beautiful architecture and history as a courthouse, less well-known is that the clocktower also served as a fire watchtower for many years in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Constructed in 1877, it was one of the tallest structures in the city at the time. At 172 feet tall, it was an ideal lookout. The watchman would ring the bells in the tower to alert volunteer firefighters. The tower was used until 1945 when the building became a police academy. It became the library we know today in 1967.

The telltale 19th-century Firehouse architecture – the arches, the red doors, the sets of windows – are easily recognizable, whether the building still functions as an FDNY firehouse, or has become a museum, a home, or a store. The reuse of these buildings highlights the layered uses of protected buildings in the Village, full of histories of literal lifesaving.

Village Firehouses Past and Present - Village Preservation

The city might at times feel like its on fire during the summer, but there have been times in the past when it has actually been. In the 1970s the Bronx was burning and Lower East Side was also suffering from fires and abandoned buildings. Before that, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire became...

124 Dekalb Avenue, Brooklyn, NY

Year Built: 1925Bedrooms/ Baths: 9 roomsSquare Footage: 5,775Price: $3,300,000

Photo: Trulia.com

Year Built: 1925

Bedrooms/ Baths: 9 rooms

Square Footage: 5,775

Price: $3,300,000

The former Engine Company 256 is another example of a firehouse divided into a two-family residence. It was once the site of Brooklyn filmmaker Spike Lee’s Forty Acres & a Mule production company, in the era of the films Jungle Fever, Do The Right Thing, Mo’ Better Blues, X, and Crooklyn.

www.cnbc.com

www.cnbc.com

Year Built: 1925Bedrooms/ Baths: 9 roomsSquare Footage: 5,775Price: $3,300,000

Photo: Trulia.com

Year Built: 1925

Bedrooms/ Baths: 9 rooms

Square Footage: 5,775

Price: $3,300,000

The former Engine Company 256 is another example of a firehouse divided into a two-family residence. It was once the site of Brooklyn filmmaker Spike Lee’s Forty Acres & a Mule production company, in the era of the films Jungle Fever, Do The Right Thing, Mo’ Better Blues, X, and Crooklyn.

Fabulous Firehouse Homes

It was recently announced that the Tribeca firehouse famous for starring in Ghostbusters is about to get vacated (along with 19 others) due to budget cuts. With news like this in New York City, thoughts turn immediately to real estate: what can be done with this newly available space? Here are...

The Little Black Firehouse

The history of this Boerum Hill renovation starts with the Civil War and ends with a rooftop archery range and soaking tub.

By Wendy Goodman Photographs by Joshua McHugh

DESIGN HUNTING

Design editor Wendy Goodman takes you inside the city's most exciting homes and design studios.

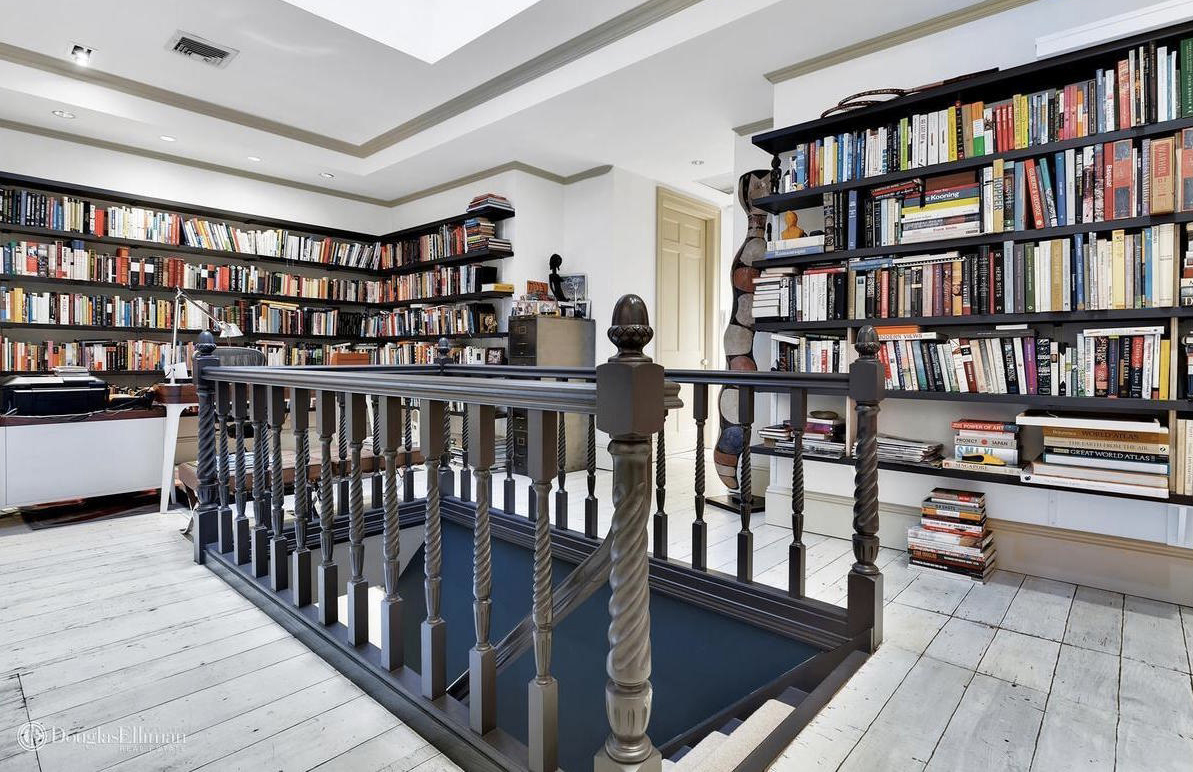

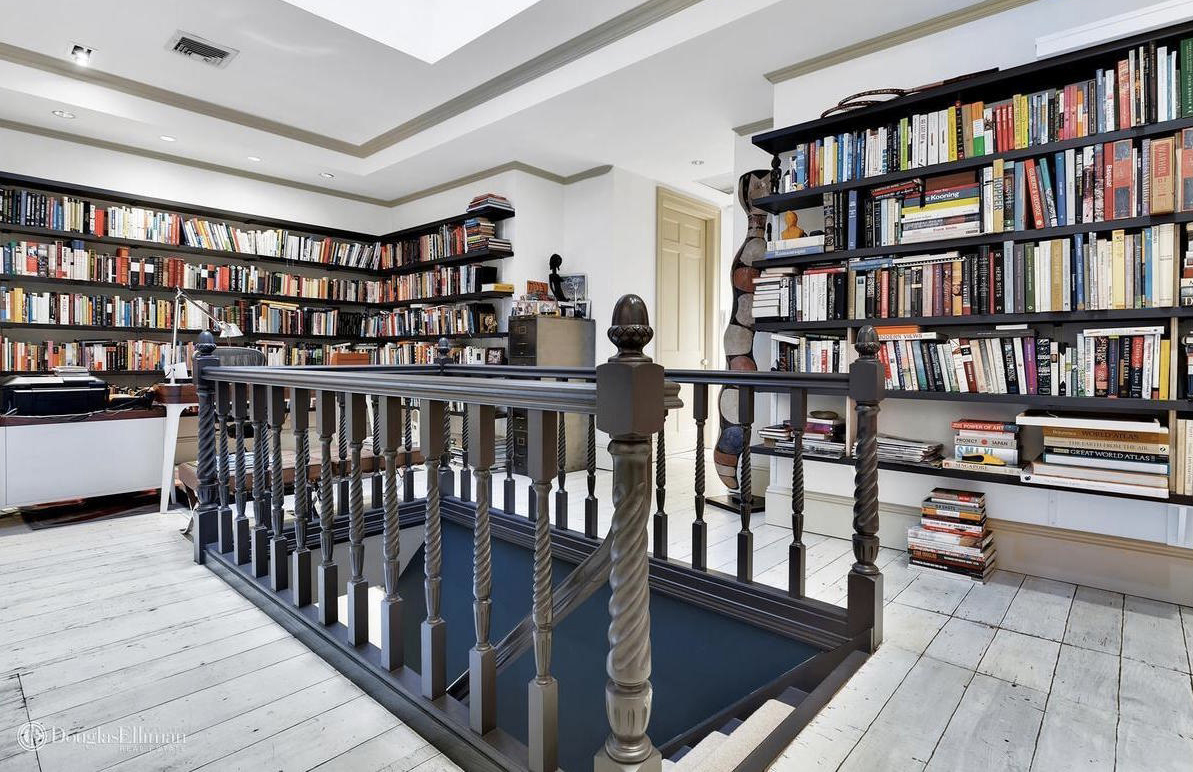

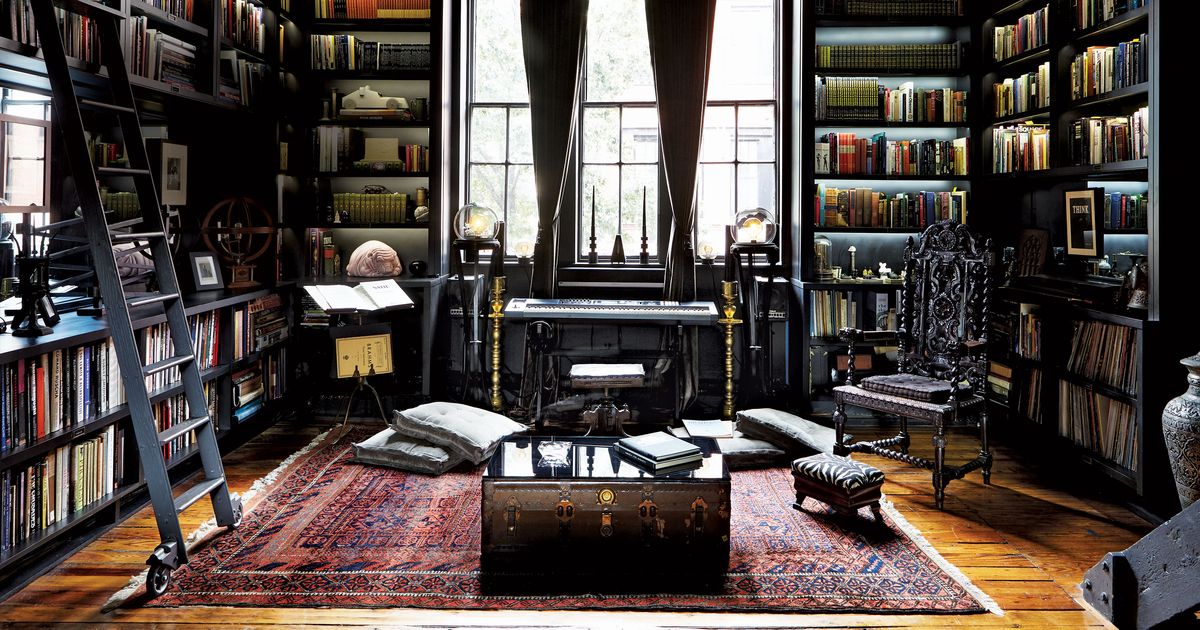

The living-room library. Photo: Joshua McHugh

Yes, the books on the occult occupy a large portion of our shelves,” says set designer Erica Hohf of the library within the mid-19th-century firehouse she shares with her husband, artist and designer Julian LaVerdiere. It’s here, nestled among the casework shelves, where their all-white leucistic boa, Phanes (who’s currently only inches long but should ultimately be six feet), will also soon hole up. “She’ll have her own custom Wardian-style case with live plants,” says LaVerdiere.

The Façade: The men of Empire Engine Company No. 19 in the 1860s. Photo: Courtesy of the homeowners

The firehouse’s original occupant, the pro-Union independent fire company Empire Engine No. 19, sent some members to serve in the Civil War (LaVerdiere and Hohf have adopted the name for their film- and commercial-design company). More than a century later, in 1984, LaVerdiere’s mother purchased the place, and her son spent his high-school years there before returning to take it over in 2014. One of his first moves was to paint much of the interior space black, which added a surprising coziness to the open plan of the kitchen, dining/work space, and library. But before anything could get under way, lots of serious structural work had to be done, including reinforcing the roof outside the kitchen and the interiors with steel. Brooklyn-based studio Dameron Architecture helped bring the couple’s ideas to life. The couple took out loans in order to bring the building up to code and lure a ground-floor tenant. It paid off: Stumptown Coffee Roasters moved in, allowing them to maximize the opportunities of inheriting this historic building.

This included the dream addition of a rooftop garden — accessed by a wall of kitchen windows containing a French door — that features an archery range, reflecting pool, and Japanese ofuro soaking tub. “It was one of those things that we always really wanted,” Hohf says. “It is traditionally used more for therapy and reflection, not partying, like an American hot tub.”

In the living-room library, above, the bookshelves were designed by owners Erica Hohf and Julian LaVerdiere and built by Bart Hutton, who worked on the casework for the recent “Heavenly Bodies” exhibition at the Met. “The only thing you focus on [in the all-black environment] are the illuminated book spines,” says LaVerdiere. “It does have a jewel-box effect,” Hohf adds. “Especially at night.”

The Kitchen: “It was formerly a very dark space,” Hohf says. “There were only a few windows, so we wanted to blow light into the house.” The wall of windows with a door to the garden beyond does just that. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Dining/Work Space: Hohf and LaVerdiere designed the massive 16-foot-long dining table after a monastery refectory table, using a plank of mahogany that had been kept for decades in LaVerdiere’s family. “It’s a serious work space,” Hohf says, “so that’s why we designed it so very long.” Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Dining-Room Wall: The Empire Engine 19 sign is a set piece made to resemble what Hohf and LaVerdiere imagined the original might look like. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Wall of Art Near Staircase: The Wieboldt’s sign on the lower left is the original plaque from a department store in Chicago owned by Hohf’s family. The painting of a gentleman is by LaVerdiere’s grandmother, who was an artist, and the Spanish maiden was in his grandmother’s collection. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Roof Garden: The soaking tub, or ofuro, as it is called in Japan, sits under the pergola at the back of the garden; in front is a skylight in the middle of the roof that doubles as a reflecting pool. Photo: Joshua McHugh

Hohf and LaVerdiere also enjoy archery in the garden and shoot at a target spinning over the ofuro. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Master Bedroom: The framed 19th-century Japanese portraits (three more hang on the opposite wall) were gifts to LaVerdiere’s great-great-grandfather, who was an emissary to Japan in 1909. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Walk-In Closet: Both Hohf’s and LaVerdiere’s wardrobes are primarily black. “I don’t even think about it anymore,” Hohf says about her choice of color. “It’s just a lifestyle.” Photo: Joshua McHugh

www.thecut.com

www.thecut.com

The history of this Boerum Hill renovation starts with the Civil War and ends with a rooftop archery range and soaking tub.

By Wendy Goodman Photographs by Joshua McHugh

DESIGN HUNTING

Design editor Wendy Goodman takes you inside the city's most exciting homes and design studios.

The living-room library. Photo: Joshua McHugh

Yes, the books on the occult occupy a large portion of our shelves,” says set designer Erica Hohf of the library within the mid-19th-century firehouse she shares with her husband, artist and designer Julian LaVerdiere. It’s here, nestled among the casework shelves, where their all-white leucistic boa, Phanes (who’s currently only inches long but should ultimately be six feet), will also soon hole up. “She’ll have her own custom Wardian-style case with live plants,” says LaVerdiere.

The Façade: The men of Empire Engine Company No. 19 in the 1860s. Photo: Courtesy of the homeowners

The firehouse’s original occupant, the pro-Union independent fire company Empire Engine No. 19, sent some members to serve in the Civil War (LaVerdiere and Hohf have adopted the name for their film- and commercial-design company). More than a century later, in 1984, LaVerdiere’s mother purchased the place, and her son spent his high-school years there before returning to take it over in 2014. One of his first moves was to paint much of the interior space black, which added a surprising coziness to the open plan of the kitchen, dining/work space, and library. But before anything could get under way, lots of serious structural work had to be done, including reinforcing the roof outside the kitchen and the interiors with steel. Brooklyn-based studio Dameron Architecture helped bring the couple’s ideas to life. The couple took out loans in order to bring the building up to code and lure a ground-floor tenant. It paid off: Stumptown Coffee Roasters moved in, allowing them to maximize the opportunities of inheriting this historic building.

This included the dream addition of a rooftop garden — accessed by a wall of kitchen windows containing a French door — that features an archery range, reflecting pool, and Japanese ofuro soaking tub. “It was one of those things that we always really wanted,” Hohf says. “It is traditionally used more for therapy and reflection, not partying, like an American hot tub.”

In the living-room library, above, the bookshelves were designed by owners Erica Hohf and Julian LaVerdiere and built by Bart Hutton, who worked on the casework for the recent “Heavenly Bodies” exhibition at the Met. “The only thing you focus on [in the all-black environment] are the illuminated book spines,” says LaVerdiere. “It does have a jewel-box effect,” Hohf adds. “Especially at night.”

The Kitchen: “It was formerly a very dark space,” Hohf says. “There were only a few windows, so we wanted to blow light into the house.” The wall of windows with a door to the garden beyond does just that. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Dining/Work Space: Hohf and LaVerdiere designed the massive 16-foot-long dining table after a monastery refectory table, using a plank of mahogany that had been kept for decades in LaVerdiere’s family. “It’s a serious work space,” Hohf says, “so that’s why we designed it so very long.” Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Dining-Room Wall: The Empire Engine 19 sign is a set piece made to resemble what Hohf and LaVerdiere imagined the original might look like. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Wall of Art Near Staircase: The Wieboldt’s sign on the lower left is the original plaque from a department store in Chicago owned by Hohf’s family. The painting of a gentleman is by LaVerdiere’s grandmother, who was an artist, and the Spanish maiden was in his grandmother’s collection. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Roof Garden: The soaking tub, or ofuro, as it is called in Japan, sits under the pergola at the back of the garden; in front is a skylight in the middle of the roof that doubles as a reflecting pool. Photo: Joshua McHugh

Hohf and LaVerdiere also enjoy archery in the garden and shoot at a target spinning over the ofuro. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Master Bedroom: The framed 19th-century Japanese portraits (three more hang on the opposite wall) were gifts to LaVerdiere’s great-great-grandfather, who was an emissary to Japan in 1909. Photo: Joshua McHugh

The Walk-In Closet: Both Hohf’s and LaVerdiere’s wardrobes are primarily black. “I don’t even think about it anymore,” Hohf says about her choice of color. “It’s just a lifestyle.” Photo: Joshua McHugh

A 19th-Century Firehouse Converted Into a Sleek, Modern Home

The history of this three-story renovation in Boerum Hill starts with the Civil War and ends with a rooftop archery range and Japanese soaking tub.

20 Beautiful New Uses for Old Firehouses You Have to See

WHAT'S OLD IS NEW AGAIN—AND LOOKS GREAT, TOO!

By ASHLEY MOOR

SEPTEMBER 17, 2018

At a certain point, as sure as rain, a city just runs out of space. And when that inevitability comes to pass, architects and city planners are faced with are two options: demolish-and-start-from-scratch, or work within the existing framework to come up with an updated, fresh-feeling design (what's known as a gut renovation, or "gut reno," among the design elite). While your city might be doing a whole lot of the former, there's one type of building that seems to be a prime and frequent candidate for the latter: midcentury firehouses.

Yes, these 20th-century relics—which were once-defunct but now serve as everything from hotels to art galleries to, depending on the depths of one's coffers, private residences—are exemplary displays of how to take the past and bring it swinging, with breathtaking beauty, into the present. For a taste of some serious architectural ingenuity and creative reconstruction, we've compiled the 20 most stunning new uses for bygone-era firehouses here. And for more jaw-dropping architecture to digest, be sure to visit these 17 American Towns So Beautiful You'll Think You're in Europe.

1

San Francisco Fire House No. 33

117 Broad St., San Francisco, California

Built in 1906, this firehouse is now privately owned by SFFD Historical Society members and "flamboyant fire buffs" Robert and Marilyn Katzman.

2

Duluth's historic Fire House No. 1

ADVERTISING

128 E. 4th St., Duluth, Minnesota

This former historic firehouse in Duluth, Minnesota has been converted into a desirable loft-living residential unit—now called the Firehouse Flats. And for more design inspiration, check out these 10 Palaces More Opulent Than Buckingham Palace.

Image via Zillow

3

Logan Circle Engine House No. 7

931 R Street NW, Washington, DC

Logan Circle Engine House No. 7 is one of the original firehouses established in Washington, D.C., in the 19th century. Now, the renovated firehouse is a $2.6 million estate, and comes complete with original furnishings, like a brass fireman's pole, wooden lockers, a roof deck, and exposed brick masonry.

Image via Sotheby's

4

East Boston fire station

64 Marion St., Boston, Massachusetts

Constructed in 1860, this firehouse is a true historical landmark in East Boston—and is now the home of a few very lucky tenants. And if you're hitting the tarmac this summer, check out The 10 Worst U.S. Airports for Summer Travel.

5

New Orleans Historic Engine 24 Firehouse

2711 Dauphine St, New Orleans, Louisiana

From a truly unique stay, book a room at The Historic Engine 24 Firehouse, located near the French Quarter in New Orleans. With many of the original furnishings still intact—not to mention a private bar—this sprawling firehouse is great for parties and events as well.

Image via Rent by Owner

6

Sailor's loft in Newport historic firehouse

Downtown, Newport, Rhode Island

With hidden rooms, an expansive bell tower, and 20th-century inspired décor, staying at this property is like taking a step back in time.

Image via Airbnb

7

Lambertville, New Jersey 19th-century firehouse

12 North Main St., Lambertville, New Jersey

This two-bedroom converted firehouse is more than just a place to rest your head at night. It's a destination complete with quirky collectibles and inimitable design.

Image via Airbnb

8

Detroit Foundation Hotel

250 W Larned St, Detroit, Michigan

For a little over a year, the former Detroit Fire Department Headquarters have undergone a staggering transformation. Now, you can book your room at the newly minted Detroit Foundation Hotel, which boasts an impressive restaurant and gorgeous views of the city.

Image via Facebook

9

Downtown Community Television Center

87 Lafayette Street, New York, New York

Founded in 1972, the Downtown Community Television Center in Manhattan, formerly a New York City firehouse, hosts a number of filmmaking events and workshops throughout the year.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

10

Anderson Cooper's Greenwich Village home

84 West 3rd St., New York, New York

The CNN anchor spent a lot of time and effort making sure his Greenwich Village home, formerly a New York City firehouse, a perfect mix of vintage and new-age—and it looks stunning. And for more awe-inspiring feats of architecture, check out these 23 Castles So Jaw-Dropping You Won't Believe They're in the U.S.

WHAT'S OLD IS NEW AGAIN—AND LOOKS GREAT, TOO!

By ASHLEY MOOR

SEPTEMBER 17, 2018

At a certain point, as sure as rain, a city just runs out of space. And when that inevitability comes to pass, architects and city planners are faced with are two options: demolish-and-start-from-scratch, or work within the existing framework to come up with an updated, fresh-feeling design (what's known as a gut renovation, or "gut reno," among the design elite). While your city might be doing a whole lot of the former, there's one type of building that seems to be a prime and frequent candidate for the latter: midcentury firehouses.

Yes, these 20th-century relics—which were once-defunct but now serve as everything from hotels to art galleries to, depending on the depths of one's coffers, private residences—are exemplary displays of how to take the past and bring it swinging, with breathtaking beauty, into the present. For a taste of some serious architectural ingenuity and creative reconstruction, we've compiled the 20 most stunning new uses for bygone-era firehouses here. And for more jaw-dropping architecture to digest, be sure to visit these 17 American Towns So Beautiful You'll Think You're in Europe.

1

San Francisco Fire House No. 33

117 Broad St., San Francisco, California

Built in 1906, this firehouse is now privately owned by SFFD Historical Society members and "flamboyant fire buffs" Robert and Marilyn Katzman.

2

Duluth's historic Fire House No. 1

ADVERTISING

128 E. 4th St., Duluth, Minnesota

This former historic firehouse in Duluth, Minnesota has been converted into a desirable loft-living residential unit—now called the Firehouse Flats. And for more design inspiration, check out these 10 Palaces More Opulent Than Buckingham Palace.

Image via Zillow

3

Logan Circle Engine House No. 7

931 R Street NW, Washington, DC

Logan Circle Engine House No. 7 is one of the original firehouses established in Washington, D.C., in the 19th century. Now, the renovated firehouse is a $2.6 million estate, and comes complete with original furnishings, like a brass fireman's pole, wooden lockers, a roof deck, and exposed brick masonry.

Image via Sotheby's

4

East Boston fire station

64 Marion St., Boston, Massachusetts

Constructed in 1860, this firehouse is a true historical landmark in East Boston—and is now the home of a few very lucky tenants. And if you're hitting the tarmac this summer, check out The 10 Worst U.S. Airports for Summer Travel.

5

New Orleans Historic Engine 24 Firehouse

2711 Dauphine St, New Orleans, Louisiana

From a truly unique stay, book a room at The Historic Engine 24 Firehouse, located near the French Quarter in New Orleans. With many of the original furnishings still intact—not to mention a private bar—this sprawling firehouse is great for parties and events as well.

Image via Rent by Owner

6

Sailor's loft in Newport historic firehouse

Downtown, Newport, Rhode Island

With hidden rooms, an expansive bell tower, and 20th-century inspired décor, staying at this property is like taking a step back in time.

Image via Airbnb

7

Lambertville, New Jersey 19th-century firehouse

12 North Main St., Lambertville, New Jersey

This two-bedroom converted firehouse is more than just a place to rest your head at night. It's a destination complete with quirky collectibles and inimitable design.

Image via Airbnb

8

Detroit Foundation Hotel

250 W Larned St, Detroit, Michigan

For a little over a year, the former Detroit Fire Department Headquarters have undergone a staggering transformation. Now, you can book your room at the newly minted Detroit Foundation Hotel, which boasts an impressive restaurant and gorgeous views of the city.

Image via Facebook

9

Downtown Community Television Center

87 Lafayette Street, New York, New York

Founded in 1972, the Downtown Community Television Center in Manhattan, formerly a New York City firehouse, hosts a number of filmmaking events and workshops throughout the year.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

10

Anderson Cooper's Greenwich Village home

84 West 3rd St., New York, New York

The CNN anchor spent a lot of time and effort making sure his Greenwich Village home, formerly a New York City firehouse, a perfect mix of vintage and new-age—and it looks stunning. And for more awe-inspiring feats of architecture, check out these 23 Castles So Jaw-Dropping You Won't Believe They're in the U.S.

11

Black Ocean offices

611 Broadway, New York, New York

This converted firehouse, built in 1895, now serves as the avant-garde headquarters for multi-faceted tech startup Black Ocean, in Manhattan.

Image via Instagram

12

Sanford Fire Station

This Sanford, Florida restored firehouse, now an opulent home, sold for more than half a million dollars.

Image via Zillow

13

Firehouse Brewing Co.

553 Philadelphia St., Indiana, Pennsylvania 15701

South Dakota's first brewpub, Firehouse Brewing Co., is housed in one Rapid City's oldest buildings—a firehouse built in 1915.

Image via Instagram

14

Waterwitch Hook and Ladder Company Nbr. 1.

33 East Street, Annapolis, Maryland

First constructed in 1885 as one of Annapolis' firehouses, then as the headquarters of Waterwitch Hook and Ladder Company Nbr. 1., this architecturally stunning building is now home to the luxurious Waterwitch Condominiums.

Image via Facebook

15

Old Firehouse No. 6

2200 Harrison Avenue Muskegon, Michigan 49441

This Muskegon firehouse-turned-home is truly unique—and only sold for $199,000 just last year.

Image via Coldwell Banker

16

Engine No. 44

3816 22nd Street, San Francisco, California

Built in 1909, the Chemical Engine House 44 in San Francisco has been real estate candy since it was renovated into this $5.7 million-dollar home.

Image via Instagram

17

Cumberland fire station home

Rolling Mill, Cumberland, Maryland

This renovated fire station in Cumberland, Maryland, has stood the test of time—along with a few changes, including the addition of beautifully wood-paneled garage doors and a pair of artistic wrought iron balconies.

18

Station 3 wedding venue

1919 Houston Ave, Houston, Texas

Fire Station 3 is Houston's original firehouse, built in 1903. Now, the fire station has been turned into an event space.

Image via Instagram

19

Plaza Fire House Museum

501 N. Los Angeles St, Los Angeles, California

The Old Plaza Firehouse is the oldest firehouse in Los Angeles—and it's is currently being used as a museum to house firefighting artifacts.

20