You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

FDNY and NYC Firehouses and Fire Companies - 2nd Section

- Thread starter mack

- Start date

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 MEDAL

PETER J. EISEMANN FF. LAD. 110 NOV. 11, 1957 1958 JOHNSTON

FF Eisemann, Ladder 110, was awarded the Johnson Medal for heroism while rescuing a man from the upper story from a tenement fire November 11, 1957.

MEDAL DAY 1958

LADDER 110 MEDAL

PETER J. EISEMANN FF. LAD. 110 NOV. 11, 1957 1958 JOHNSTON

FF Eisemann, Ladder 110, was awarded the Johnson Medal for heroism while rescuing a man from the upper story from a tenement fire November 11, 1957.

MEDAL DAY 1958

Last edited:

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 MEDAL

KEVIN C. KANE FF. LAD. 110 SEP. 12, 1991 1992 BROOKLYN CITIZENS

FF Kane, Ladder 110, was awarded the Brooklyn Citizens Medal posthumously for heroic duty performance at a fire on September 12, 1991.

LODD - FF KEVIN C. KANE SEPTEMBER 13, 1991

LADDER 110 MEDAL

KEVIN C. KANE FF. LAD. 110 SEP. 12, 1991 1992 BROOKLYN CITIZENS

FF Kane, Ladder 110, was awarded the Brooklyn Citizens Medal posthumously for heroic duty performance at a fire on September 12, 1991.

LODD - FF KEVIN C. KANE SEPTEMBER 13, 1991

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 MEDAL

ROBERT PAV CAPT. LAD. 110 2006 CINELLI

Residents of the borough of Brooklyn have come to know that when they sound an alarm for a fire or other emergency, the Fire Department of New York will respond in the shortest amount of time possible. Moreover, people have come to expect that the FDNY will handle the situation properly and professionally--with the protection of life as the top priority.

Such was the case with Ladder Company 110, when members were called to respond to an alarm for a fire at 417 Baltic Street. The combination of a great turnout, quick response and personal bravery exhibited by Captain Robert Pav proved responsible for saving a 73-year-old woman’s life.

On the morning of May 12, 2005, the members of Ladder 110 responded to fire alarm Box number 550 from their quarters on Tillary Street. While en-route to the Baltic Street address, the Department radio was coming alive with reports of people trapped.

Arriving at this 14-story, high-rise multiple dwelling, FFs Kevin Harvey with the extinguisher and Terence Brody with forcible entry tools, under the supervision of Captain Pav, made their way up to the 12th floor, the reported fire floor. Reaching the 12th floor, Ladder 110’s inside team was met with a severe smoke condition, as well as a radio communication from Battalion Chief Jack Oehm, Battalion 32 that a woman appeared at a smoke-filled window, threatening to jump. As Ladder 110 was forcing entry into the fire apartment (apartment 12D) and Engine 226 was preparing an attack on the fire with a 21/2-inch standpipe line, the members of Squad Company 1 were initiating a lifesaving rope rescue from the apartment directly over the fire apartment.

With little time to spare and a hose-line being stretched from the stairway, Captain Pav entered the fire apartment. Despite high heat and zero visibility, he was determined to save a life. Immediately on entering the apartment, the Captain was met with a free-burning living-room fire that was rolling over into the apartment hallway.

It was evident that the only way to get to the rear bedroom where the trapped occupant was located would be to crawl under and past the fire. After passing fire now being held back by FF Harvey with a fire extinguisher, Captain Pav was able to reach a rear bedroom and find Dorothy Bradford crouched behind the bed next to an open window. She was gasping for air. Removing his facepiece and putting it on the 73-year-old victim, Captain Pav dragged her past the living-room fire and into an adjacent apartment for safe refuge.

Captain Robert Pav of Ladder Company 110 conducted his search and rescue without the benefit of a charged hose-line. He passed a heavy body of fire to effect his lifesaving rescue. The trapped occupant, 73-year-old Dorothy Bradford, is alive and well, thanks to the deliberate and

calculated actions of Captain Pav. For these reasons, For these reasons, he is presented with the Dr. Albert A. Cinelli Medal.

LADDER 110 MEDAL

ROBERT PAV CAPT. LAD. 110 2006 CINELLI

Residents of the borough of Brooklyn have come to know that when they sound an alarm for a fire or other emergency, the Fire Department of New York will respond in the shortest amount of time possible. Moreover, people have come to expect that the FDNY will handle the situation properly and professionally--with the protection of life as the top priority.

Such was the case with Ladder Company 110, when members were called to respond to an alarm for a fire at 417 Baltic Street. The combination of a great turnout, quick response and personal bravery exhibited by Captain Robert Pav proved responsible for saving a 73-year-old woman’s life.

On the morning of May 12, 2005, the members of Ladder 110 responded to fire alarm Box number 550 from their quarters on Tillary Street. While en-route to the Baltic Street address, the Department radio was coming alive with reports of people trapped.

Arriving at this 14-story, high-rise multiple dwelling, FFs Kevin Harvey with the extinguisher and Terence Brody with forcible entry tools, under the supervision of Captain Pav, made their way up to the 12th floor, the reported fire floor. Reaching the 12th floor, Ladder 110’s inside team was met with a severe smoke condition, as well as a radio communication from Battalion Chief Jack Oehm, Battalion 32 that a woman appeared at a smoke-filled window, threatening to jump. As Ladder 110 was forcing entry into the fire apartment (apartment 12D) and Engine 226 was preparing an attack on the fire with a 21/2-inch standpipe line, the members of Squad Company 1 were initiating a lifesaving rope rescue from the apartment directly over the fire apartment.

With little time to spare and a hose-line being stretched from the stairway, Captain Pav entered the fire apartment. Despite high heat and zero visibility, he was determined to save a life. Immediately on entering the apartment, the Captain was met with a free-burning living-room fire that was rolling over into the apartment hallway.

It was evident that the only way to get to the rear bedroom where the trapped occupant was located would be to crawl under and past the fire. After passing fire now being held back by FF Harvey with a fire extinguisher, Captain Pav was able to reach a rear bedroom and find Dorothy Bradford crouched behind the bed next to an open window. She was gasping for air. Removing his facepiece and putting it on the 73-year-old victim, Captain Pav dragged her past the living-room fire and into an adjacent apartment for safe refuge.

Captain Robert Pav of Ladder Company 110 conducted his search and rescue without the benefit of a charged hose-line. He passed a heavy body of fire to effect his lifesaving rescue. The trapped occupant, 73-year-old Dorothy Bradford, is alive and well, thanks to the deliberate and

calculated actions of Captain Pav. For these reasons, For these reasons, he is presented with the Dr. Albert A. Cinelli Medal.

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 MEDAL

TERENCE F. BRODY FF. LAD. 110 2006 KANE

Firefighting is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world. Firefighters must enter burning structures. Once inside, they must search for victims, the source of the fire and then extinguish the fire. During this process, Firefighters are exposed to extreme heat, toxic smoke and

debilitating fatigue. Ultimately, firefighting is a physically demanding job. Firefighters carry 80 to 100 pounds of equipment, such as rolled hose, sledge hammers, axes, hydraulic rams and pressurized extinguishers, into and around the fire scene to rescue people and put out the

fire.

On the morning of May 12, 2005, the members of Ladder Company 110 responded to fire alarm Box number 550 from their quarters on Tillary Street. While en-route to the Baltic Street address, the Department radio crackled with reports of people trapped.

Arriving at the 14-story, highrise multiple dwelling, FFs Kevin Harvey with the extinguisher and Terence Brody with forcible entry tools, supervised by Captain Robert Pav, would have to extend their physical abilities almost to the breaking point as they were confronted with a fire on the 12th floor and a confirmed life hazard. They took the elevator to the 10th floor. After previous difficulty, the elevator opened. With time running out for a victim threatening to jump from a smoke-filled, 12th-floor window, the arriving rescuers began their painstaking run up to the fire floor, weighted down by a full complement of tools.

Arriving at apartment 12D, FF Brody’s job was just beginning. It was time to force entry and make a search, while simultaneously pushing past the physical fatigue. As FF Brody was forcing entry into the fire apartment and Engine Company 226 was preparing an attack on the fire with a 21/2-

inch line stretched off the building’s standpipe system, the members of Squad 1 were initiating a lifesaving rope rescue from the apartment directly over the fire apartment.

With no time to spare and a hose-line being stretched from the stairway, Captain Pav entered the fire apartment with his inside team, in spite of the high heat and zero visibility. Immediately on entering the apartment, the Captain and FF Brody were met with a free-burning living-room fire that was rolling over into the apartment hallway.

It became quite evident that the only way to get to the rear bedroom where the trapped occupant was located would be to crawl under and past the fire. After passing the fire now being held back by FF Harvey with a fire extinguisher, FF Brody managed to reach a rear bedroom and find

Jacqueline Bradford, age 35, crouched behind the bed next to an open window. She was gasping for air. The Firefighter told her to hold her breath as he shielded her with his body. They escaped past the living-room fire and into an adjacent apartment for safe refuge.

FF Terence F. Brody of Ladder Company 110 conducted his search and rescue without the benefit of a charged hoseline. He passed a heavy body of fire to accomplish his lifesaving task. The young woman who had been trapped by fire is alive and well today because of the individual bravery of FF

Brody. For these reasons, he is honored with the Firefighter Kevin C. Kane Medal.

CAPTAIN TERENCE BRODY - AUTHOR

ROSEWOOD BOOKS

Terence Brody

Terence Brody is an active captain on the FDNY, assigned to Ladder 10 in lower Manhattan. He has been writing screenplays for twenty years. Two of his feature scripts, Rescuing Madison and A Lesson in Romance, were produced and aired on the Hallmark Channel. His script, Renovate My Heart, will air on TV later this year. Renovate My Heart, the novel, co-written with author Lindy Miller, releases Sept 2020. Brody is currently writing the screenplay for the novella Snowed In by Lindy Miller (Nov 2020).

Brody loves being a New York firefighter, but his other passions are screenwriting and spending time with his wife and two children. They reside in Long Island, New York.

https://vesuvianmedia.com/terence-b...dy is an active,aired on the Hallmark Channel.

LADDER 110 MEDAL

TERENCE F. BRODY FF. LAD. 110 2006 KANE

Firefighting is one of the most dangerous occupations in the world. Firefighters must enter burning structures. Once inside, they must search for victims, the source of the fire and then extinguish the fire. During this process, Firefighters are exposed to extreme heat, toxic smoke and

debilitating fatigue. Ultimately, firefighting is a physically demanding job. Firefighters carry 80 to 100 pounds of equipment, such as rolled hose, sledge hammers, axes, hydraulic rams and pressurized extinguishers, into and around the fire scene to rescue people and put out the

fire.

On the morning of May 12, 2005, the members of Ladder Company 110 responded to fire alarm Box number 550 from their quarters on Tillary Street. While en-route to the Baltic Street address, the Department radio crackled with reports of people trapped.

Arriving at the 14-story, highrise multiple dwelling, FFs Kevin Harvey with the extinguisher and Terence Brody with forcible entry tools, supervised by Captain Robert Pav, would have to extend their physical abilities almost to the breaking point as they were confronted with a fire on the 12th floor and a confirmed life hazard. They took the elevator to the 10th floor. After previous difficulty, the elevator opened. With time running out for a victim threatening to jump from a smoke-filled, 12th-floor window, the arriving rescuers began their painstaking run up to the fire floor, weighted down by a full complement of tools.

Arriving at apartment 12D, FF Brody’s job was just beginning. It was time to force entry and make a search, while simultaneously pushing past the physical fatigue. As FF Brody was forcing entry into the fire apartment and Engine Company 226 was preparing an attack on the fire with a 21/2-

inch line stretched off the building’s standpipe system, the members of Squad 1 were initiating a lifesaving rope rescue from the apartment directly over the fire apartment.

With no time to spare and a hose-line being stretched from the stairway, Captain Pav entered the fire apartment with his inside team, in spite of the high heat and zero visibility. Immediately on entering the apartment, the Captain and FF Brody were met with a free-burning living-room fire that was rolling over into the apartment hallway.

It became quite evident that the only way to get to the rear bedroom where the trapped occupant was located would be to crawl under and past the fire. After passing the fire now being held back by FF Harvey with a fire extinguisher, FF Brody managed to reach a rear bedroom and find

Jacqueline Bradford, age 35, crouched behind the bed next to an open window. She was gasping for air. The Firefighter told her to hold her breath as he shielded her with his body. They escaped past the living-room fire and into an adjacent apartment for safe refuge.

FF Terence F. Brody of Ladder Company 110 conducted his search and rescue without the benefit of a charged hoseline. He passed a heavy body of fire to accomplish his lifesaving task. The young woman who had been trapped by fire is alive and well today because of the individual bravery of FF

Brody. For these reasons, he is honored with the Firefighter Kevin C. Kane Medal.

CAPTAIN TERENCE BRODY - AUTHOR

ROSEWOOD BOOKS

Terence Brody

Terence Brody is an active captain on the FDNY, assigned to Ladder 10 in lower Manhattan. He has been writing screenplays for twenty years. Two of his feature scripts, Rescuing Madison and A Lesson in Romance, were produced and aired on the Hallmark Channel. His script, Renovate My Heart, will air on TV later this year. Renovate My Heart, the novel, co-written with author Lindy Miller, releases Sept 2020. Brody is currently writing the screenplay for the novella Snowed In by Lindy Miller (Nov 2020).

Brody loves being a New York firefighter, but his other passions are screenwriting and spending time with his wife and two children. They reside in Long Island, New York.

https://vesuvianmedia.com/terence-b...dy is an active,aired on the Hallmark Channel.

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 MEDAL

ADAM C. BISHOP FF. LAD. 170 ASSIGNED - LAD. 110 DETAILED APRIL 12, 2014 2015 PULASKI

FF Adam C. Bishop, a six-and-a-half year veteran of the Department, is assigned to Ladder 170. On April 12, 2014, he found himself working a day tour as outside vent Firefighter in Ladder 110 on a balmy, 70-degree spring day. At 1008 hours, on his first run of the day, FF Bishop encountered a situation far more memorable than the nice weather.

The alarm was for a structural fire on Lafayette Avenue. A signal 10-75 was transmitted by Engine 210 for a working fire in a five-story brownstone building without a rear fire escape. First-due Ladder 105 was setting up their bucket in front of the building on Lafayette Avenue, as second-due Ladder 110 arrived via Vanderbilt Avenue, on the exposure #2 side of the fire building.

FF Bishop and Ladder 110’s chauffeur, FF Robert Ruggirello, saw a man hanging from a fifth-floor window at therear of the third building in from the corner. Heavy smoke was boiling from his fifth-floor window and from windows on the floor below him as he hung by his fingertips. The man had opened his hallway door in an attempt to escape from the building, inadvertently providing a flow path for the intensely hot fire gases into his apartment, forcing him into his current precarious location. FF Bishop knew that the man would not be able to maintain his position for long.

Racing against time, FFs Bishop and Ruggirello set up the truck to facilitate a ladder rescue. Due to the presence of a large tree and street obstructions, optimal positioning was not possible. To effect the rescue, FF Bishop had to operate on a ladder that was unsupported at the tip and reached only the fourth floor. Despite being aware of the dangerous strains placed on the ladder, FF Bishop, who is 6’8” and 280 lbs. without his gear, climbed the ladder up through tree branches, breaking large branches in his way to clear a path to the top rung of the ladder.

Standing on the top rung, FF Bishop braced himself against the building, but was unable to grasp the victim. He had to lean out, over the ladder’s tip and away from the building to reach the victim. Leaning out and no longer braced against the building, FF Bishop reached for and grasped the man and pulled him back and safely down onto the ladder.

FF Bishop began calming the distraught man who, panic-stricken, was frozen to the ladder rungs. Speaking quietly to the victim, the Firefighter reassured him that he was safe and encouraged him to start backing down the ladder. As he spoke, broken window glass began to rain down upon them and the rescuer shielded the victim with his body until it stopped. FF Bishop’s efforts to calm the man were successful and they both proceeded down the ladder. After ensuring that the victim was safely on the ground, FF Bishop continued to operate as Ladder 110’s outside vent Firefighter.

FF Bishop’s composed resourcefulness, his willingness to put himself in such an unstable position on the tip of a cantilever ladder and then to reach out over a four-story drop to retrieve the victim, demonstrates the bravery, initiative and capability deserving of this medal. The victim certainly would have, in a few short minutes, lost his tenuous grip on the window ledge and plummeted to his death, had it not been for FF Bishop’s extraordinary effort. FF Adam C. Bishop, well aware of the risks involved in his actions, performed professionally and is truly a credit to the Department. For these reasons, he is presented with the Pulaski Association Medal.

LADDER 110 MEDAL

ADAM C. BISHOP FF. LAD. 170 ASSIGNED - LAD. 110 DETAILED APRIL 12, 2014 2015 PULASKI

FF Adam C. Bishop, a six-and-a-half year veteran of the Department, is assigned to Ladder 170. On April 12, 2014, he found himself working a day tour as outside vent Firefighter in Ladder 110 on a balmy, 70-degree spring day. At 1008 hours, on his first run of the day, FF Bishop encountered a situation far more memorable than the nice weather.

The alarm was for a structural fire on Lafayette Avenue. A signal 10-75 was transmitted by Engine 210 for a working fire in a five-story brownstone building without a rear fire escape. First-due Ladder 105 was setting up their bucket in front of the building on Lafayette Avenue, as second-due Ladder 110 arrived via Vanderbilt Avenue, on the exposure #2 side of the fire building.

FF Bishop and Ladder 110’s chauffeur, FF Robert Ruggirello, saw a man hanging from a fifth-floor window at therear of the third building in from the corner. Heavy smoke was boiling from his fifth-floor window and from windows on the floor below him as he hung by his fingertips. The man had opened his hallway door in an attempt to escape from the building, inadvertently providing a flow path for the intensely hot fire gases into his apartment, forcing him into his current precarious location. FF Bishop knew that the man would not be able to maintain his position for long.

Racing against time, FFs Bishop and Ruggirello set up the truck to facilitate a ladder rescue. Due to the presence of a large tree and street obstructions, optimal positioning was not possible. To effect the rescue, FF Bishop had to operate on a ladder that was unsupported at the tip and reached only the fourth floor. Despite being aware of the dangerous strains placed on the ladder, FF Bishop, who is 6’8” and 280 lbs. without his gear, climbed the ladder up through tree branches, breaking large branches in his way to clear a path to the top rung of the ladder.

Standing on the top rung, FF Bishop braced himself against the building, but was unable to grasp the victim. He had to lean out, over the ladder’s tip and away from the building to reach the victim. Leaning out and no longer braced against the building, FF Bishop reached for and grasped the man and pulled him back and safely down onto the ladder.

FF Bishop began calming the distraught man who, panic-stricken, was frozen to the ladder rungs. Speaking quietly to the victim, the Firefighter reassured him that he was safe and encouraged him to start backing down the ladder. As he spoke, broken window glass began to rain down upon them and the rescuer shielded the victim with his body until it stopped. FF Bishop’s efforts to calm the man were successful and they both proceeded down the ladder. After ensuring that the victim was safely on the ground, FF Bishop continued to operate as Ladder 110’s outside vent Firefighter.

FF Bishop’s composed resourcefulness, his willingness to put himself in such an unstable position on the tip of a cantilever ladder and then to reach out over a four-story drop to retrieve the victim, demonstrates the bravery, initiative and capability deserving of this medal. The victim certainly would have, in a few short minutes, lost his tenuous grip on the window ledge and plummeted to his death, had it not been for FF Bishop’s extraordinary effort. FF Adam C. Bishop, well aware of the risks involved in his actions, performed professionally and is truly a credit to the Department. For these reasons, he is presented with the Pulaski Association Medal.

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 LODDS

FIREFIGHTER JOHN J. CAREY LADDER 110 SEPTEMBER 28, 1907

Brooklyn Box 33-155

FF Carey, Ladder 60 (Ladder 110) was killed in a collision with Engine 126 (Engine 226) at 7:20 PM responding to Brooklyn Box 33-155 for a fire in a grocery store cellar. The collision was at the intersection of Smith Street and Atlantic Avenue. The companies were responding in heavy rain.

FIREFIGHTER FRANCIS V.A. MAHER LADDER 110 DECEMBER 23, 1909

He died as a result of injuries sustained while responding to an alarm on April 26th.

CAPTAIN JAMES A. HAGEN LADDER 110 NOVEMBER 3, 1911

Foreman James A. Hagen of Engine 107 (now Engine 207) fell through the skylight of the Veneer Barrel Company at 62 Water Street. The Foreman’s motto was “I will not send my men where I will not go myself.” Hagen was on the roof with his men in dense smoke when he tripped over the baseboard of the skylight, which sent him through it. He fell thirty feet and struck some beams on the way down, fracturing his skull. Death was instantaneous. He was in the Department for ten years and rose through the ranks quickly. He was to celebrate his third wedding anniversary in two days. Beside his wife, he left behind a sixteen-month-old daughter. He was thirty-four years old. -from "The Last Alarm

FUNERAL - FOREMAN HOGAN

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

LADDER 110 LODDS

FIREFIGHTER JOHN J. CAREY LADDER 110 SEPTEMBER 28, 1907

Brooklyn Box 33-155

FF Carey, Ladder 60 (Ladder 110) was killed in a collision with Engine 126 (Engine 226) at 7:20 PM responding to Brooklyn Box 33-155 for a fire in a grocery store cellar. The collision was at the intersection of Smith Street and Atlantic Avenue. The companies were responding in heavy rain.

FIREFIGHTER FRANCIS V.A. MAHER LADDER 110 DECEMBER 23, 1909

He died as a result of injuries sustained while responding to an alarm on April 26th.

CAPTAIN JAMES A. HAGEN LADDER 110 NOVEMBER 3, 1911

Foreman James A. Hagen of Engine 107 (now Engine 207) fell through the skylight of the Veneer Barrel Company at 62 Water Street. The Foreman’s motto was “I will not send my men where I will not go myself.” Hagen was on the roof with his men in dense smoke when he tripped over the baseboard of the skylight, which sent him through it. He fell thirty feet and struck some beams on the way down, fracturing his skull. Death was instantaneous. He was in the Department for ten years and rose through the ranks quickly. He was to celebrate his third wedding anniversary in two days. Beside his wife, he left behind a sixteen-month-old daughter. He was thirty-four years old. -from "The Last Alarm

FUNERAL - FOREMAN HOGAN

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

Last edited:

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

ENGINE 207 LODD

CAPTAIN JOSEPH FITZGERALD ENGINE 207 DECEMBER 18, 1918

Captain Fitzgerald, Engine 207, was killed when he was knocked off a ladder from the 3rd floor by a falling window while operating at a fire.

FIRE BUILDING 301-303 ADAMS STREET

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

ENGINE 207 LODD

CAPTAIN JOSEPH FITZGERALD ENGINE 207 DECEMBER 18, 1918

Captain Fitzgerald, Engine 207, was killed when he was knocked off a ladder from the 3rd floor by a falling window while operating at a fire.

FIRE BUILDING 301-303 ADAMS STREET

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

Last edited:

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

ENGINE 207 LODD

FIREFIGHTER MICHAEL J. MULVEY ENGINE 207 MARCH 7, 1937

Fireman Michael J. Mulvey of Engine 207 was overcome by smoke while battling a three-alarm fire in a nine-story building. The fire in a tinware factory was confined to paints and chemicals on the first and second floors. Fireman Mulvey and several other members of Engine 207 were on a landing when they were forced back by heavy smoke. Once they regrouped they found that Mulvey was missing. Two members of Rescue 2, wearing air-masks, entered the building and after several minutes brought the lifeless body of Mulvey out. They worked over him for over half an hour with an inhalator but failed to revive him. He was a member of the Department for eighteen years. -from "The Last Alarm"

FUNERAL - FF MULVEY

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

ENGINE 207 LODD

FIREFIGHTER MICHAEL J. MULVEY ENGINE 207 MARCH 7, 1937

Fireman Michael J. Mulvey of Engine 207 was overcome by smoke while battling a three-alarm fire in a nine-story building. The fire in a tinware factory was confined to paints and chemicals on the first and second floors. Fireman Mulvey and several other members of Engine 207 were on a landing when they were forced back by heavy smoke. Once they regrouped they found that Mulvey was missing. Two members of Rescue 2, wearing air-masks, entered the building and after several minutes brought the lifeless body of Mulvey out. They worked over him for over half an hour with an inhalator but failed to revive him. He was a member of the Department for eighteen years. -from "The Last Alarm"

FUNERAL - FF MULVEY

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 LODD

FIREFIGHTER KEVIN C. KANE LADDER 110 SEPTEMBER 13, 1991

NYC Fire Wire

September 12, 2013 · Atlantic Beach, NY ·

September 12th, 1991, FF Kevin C Kane L-110 made the ultimate sacrifice, on September 13th, 1991 he succumbed to his injuries.

Shortly before dawn on Sept. 12, 1991, smoke poured from an apartment in an abandoned building in the East New York section of Brooklyn. At the apartment's entrance, firefighters with Ladder Company 110 passed members of Engine Company 236, who had directed their hose into the apartment.

Engine 236 was working with four instead of five firefighters because of staff reductions. As a result, the firefighter holding the nozzle of the hose cautioned the ladder company, Engine 236 did not have enough hose line on hand to reach the back room where the ladder team was headed.

But the search for victims could not wait, and the ladder company disappeared into the darkness. Moments later, a fiery section of the bedroom ceiling came crashing down on Firefighter Kevin Kane, 31. His screams anguished firefighters who tried, but failed, to make their way past the burning timbers.

Engine 236 rushed to pull up additional lengths of hose so that the stream of water could reach the back room. When Firefighter Kane leaped from a window minutes later into the bucket of a tower ladder, he had severe burns over 80 percent of his body. He died the next day.

Story courtesy of NY Times Archives

FIREBOAT KEVIN C. KANE

The fireboat was commissioned in 1993 and named the Kevin C. Kane, in honor of a probationary firefighter who died in the line of duty in 1991. According to New York Fire Department literature, the Kane will hit 28 knots (approximately 32 mph) and its water cannons could pump 6,400 gallons a minute. The Kane served the NYC Fire Department Marine Division for 20 years before being replaced by a bigger, faster fireboat, but during that time she went from a supplementary vessel to the principal fireboat assigned to Marine Co. 6 in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. It was one of the responders to U.S. Airways Flight 1549 on January 15, 2009, when that craft struck a flock of Canada geese and lost engine power, forcing the pilots to ditch the plane in the Hudson River, an incident known as the “Miracle on the Hudson.”

The Kevin C. Kane was formerly an FDNY fireboat and is currently being refitted as a long-haul tugboat. She was commissioned in 1992, participated in two high-profile events: responding to al Qaeda's attack on the World Trade Center, on September 11, 2001; the rescue of airline passengers from the airliner that landed on the Hudson River. She was auctioned off after she incurred damage during Hurricane Sandy. The vessel was named after a firefighter who lost his life in the line of duty.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kevin_C._Kane

January 14, 2015

Firefighters at Marine 6 Present Special Gifts to Family of Fallen FF Kevin Kane

Members of Marine 6 with the Kane family. They are holding the sideboard, portrait of Kevin Kane and framed poem.

Probationary Firefighter Kevin Kane, from Ladder 110, was 30-years-old and had only 10 months on the job when he was killed at a fire in East New York on Sept. 12, 1991.

The following year, a new fireboat was dedicated and named to honor the hero – the ‘Kevin C. Kane.’

“It was a solid, very reliable boat,” Capt. Louis Guzzo, Marine 6, said. “It would always just keep going – it never stopped or failed us.”

The boat was 50-by-16 feet with a four foot draft. It reached speeds of 30 to 35 knots and could pump 5,000 gallons of water a minute – the equivalent of five fire engines.

During its 20-year tenure, the boat responded to many multiple-alarm fires throughout New York City and was integral in the response to US Airways flight 1549 (dubbed the Miracle on the Hudson) in January 2009.

Yet on Oct. 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy hit New York City and flooded the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

“The boat was flooded and irreversibly damaged,” Capt. Guzzo said.

It was eventually decommissioned and sold, but the man for whom the boat was named was never forgotten. So in January, the members of Marine 6 invited the Kane family to quarters for a special presentation.

Members of the firehouse gave his family one of the boat’s sideboards, bearing the name of the hero (the other now hangs in the quarters of Marine 6). Firefighter Mark Barrett, Marine 6, also painted a portrait of Firefighter Kane, with his namesake fireboat operating in the background.

And they reminded the family that Firefighter Kane will never be forgotten.

“When you work on a boat, you always want to make sure you do the right thing at an emergency,” Capt. Guzzo said. “Not only because you’re a part of the FDNY, but also to honor whom boat is named after.”

The firefighter’s brother, Raymond Kane, also presented the members with a special poem honoring the event, which now hangs prominently at Marine 6.

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

LADDER 110 LODD

FIREFIGHTER KEVIN C. KANE LADDER 110 SEPTEMBER 13, 1991

NYC Fire Wire

September 12, 2013 · Atlantic Beach, NY ·

September 12th, 1991, FF Kevin C Kane L-110 made the ultimate sacrifice, on September 13th, 1991 he succumbed to his injuries.

Shortly before dawn on Sept. 12, 1991, smoke poured from an apartment in an abandoned building in the East New York section of Brooklyn. At the apartment's entrance, firefighters with Ladder Company 110 passed members of Engine Company 236, who had directed their hose into the apartment.

Engine 236 was working with four instead of five firefighters because of staff reductions. As a result, the firefighter holding the nozzle of the hose cautioned the ladder company, Engine 236 did not have enough hose line on hand to reach the back room where the ladder team was headed.

But the search for victims could not wait, and the ladder company disappeared into the darkness. Moments later, a fiery section of the bedroom ceiling came crashing down on Firefighter Kevin Kane, 31. His screams anguished firefighters who tried, but failed, to make their way past the burning timbers.

Engine 236 rushed to pull up additional lengths of hose so that the stream of water could reach the back room. When Firefighter Kane leaped from a window minutes later into the bucket of a tower ladder, he had severe burns over 80 percent of his body. He died the next day.

Story courtesy of NY Times Archives

FIREBOAT KEVIN C. KANE

The fireboat was commissioned in 1993 and named the Kevin C. Kane, in honor of a probationary firefighter who died in the line of duty in 1991. According to New York Fire Department literature, the Kane will hit 28 knots (approximately 32 mph) and its water cannons could pump 6,400 gallons a minute. The Kane served the NYC Fire Department Marine Division for 20 years before being replaced by a bigger, faster fireboat, but during that time she went from a supplementary vessel to the principal fireboat assigned to Marine Co. 6 in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. It was one of the responders to U.S. Airways Flight 1549 on January 15, 2009, when that craft struck a flock of Canada geese and lost engine power, forcing the pilots to ditch the plane in the Hudson River, an incident known as the “Miracle on the Hudson.”

The Kevin C. Kane was formerly an FDNY fireboat and is currently being refitted as a long-haul tugboat. She was commissioned in 1992, participated in two high-profile events: responding to al Qaeda's attack on the World Trade Center, on September 11, 2001; the rescue of airline passengers from the airliner that landed on the Hudson River. She was auctioned off after she incurred damage during Hurricane Sandy. The vessel was named after a firefighter who lost his life in the line of duty.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kevin_C._Kane

January 14, 2015

Firefighters at Marine 6 Present Special Gifts to Family of Fallen FF Kevin Kane

Members of Marine 6 with the Kane family. They are holding the sideboard, portrait of Kevin Kane and framed poem.

Probationary Firefighter Kevin Kane, from Ladder 110, was 30-years-old and had only 10 months on the job when he was killed at a fire in East New York on Sept. 12, 1991.

The following year, a new fireboat was dedicated and named to honor the hero – the ‘Kevin C. Kane.’

“It was a solid, very reliable boat,” Capt. Louis Guzzo, Marine 6, said. “It would always just keep going – it never stopped or failed us.”

The boat was 50-by-16 feet with a four foot draft. It reached speeds of 30 to 35 knots and could pump 5,000 gallons of water a minute – the equivalent of five fire engines.

During its 20-year tenure, the boat responded to many multiple-alarm fires throughout New York City and was integral in the response to US Airways flight 1549 (dubbed the Miracle on the Hudson) in January 2009.

Yet on Oct. 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy hit New York City and flooded the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

“The boat was flooded and irreversibly damaged,” Capt. Guzzo said.

It was eventually decommissioned and sold, but the man for whom the boat was named was never forgotten. So in January, the members of Marine 6 invited the Kane family to quarters for a special presentation.

Members of the firehouse gave his family one of the boat’s sideboards, bearing the name of the hero (the other now hangs in the quarters of Marine 6). Firefighter Mark Barrett, Marine 6, also painted a portrait of Firefighter Kane, with his namesake fireboat operating in the background.

And they reminded the family that Firefighter Kane will never be forgotten.

“When you work on a boat, you always want to make sure you do the right thing at an emergency,” Capt. Guzzo said. “Not only because you’re a part of the FDNY, but also to honor whom boat is named after.”

The firefighter’s brother, Raymond Kane, also presented the members with a special poem honoring the event, which now hangs prominently at Marine 6.

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

Attachments

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 LODD

FIREFIGHTER KEVIN C. KANE LADDER 110 SEPTEMBER 13, 1991

A Firefighter's Death as a Rallying Cry; Fatal Blaze in '91 Comes to Symbolize Dangers of Cutbacks

By Michelle O'Donnell

June 2, 2003

Shortly before dawn on Sept. 12, 1991, smoke poured from an apartment in an abandoned building in the East New York section of Brooklyn. At the apartment's entrance, firefighters with Ladder Company 110 passed members of Engine Company 236, who had directed their hose into the apartment.

Engine 236 was working with four instead of five firefighters because of staff reductions. As a result, the firefighter holding the nozzle of the hose cautioned the ladder company, Engine 236 did not have enough hose line on hand to reach the back room where the ladder team was headed.

But the search for victims could not wait, and the ladder company disappeared into the darkness. Moments later, a fiery section of the bedroom ceiling came crashing down on Firefighter Kevin Kane, 31. His screams anguished firefighters who tried, but failed, to make their way past the burning timbers.

Engine 236 rushed to pull up additional lengths of hose so that the stream of water could reach the back room. When Firefighter Kane leaped from a window minutes later into the bucket of a tower ladder, he had severe burns over 80 percent of his body. He died the next day.

To many firefighters, the 1991 fire has become known as the Kevin Kane fire, emblematic of the dangers of reducing engine staffing. Each time the city broaches the subject of formally reducing all engine crews to four members, as it has in recent months, the story of the Kevin Kane fire is retold in firehouses around the city.

But the story of the fire, like the issue it has come to symbolize, is complicated, deeply emotional and, in truth, not well understood.

The city, for instance, has always rebutted the claim that having one firefighter fewer in the crew of Engine 236 that day played a role in Firefighter Kane's death. Indeed, the question of how many firefighters can safely work in engine crews has been a thorny one for decades.

Firefighters say that, in one sense, no number of crew members can ensure complete safety. They believe that any reduction is reckless, and they argue that the move by the city in recent months to reduce the last 53 engines operating with five firefighters to four is intolerable.

City officials, including senior members of the Fire Department, have called such complaints little more than fear-mongering. They note emphatically that 150 engines operating out of firehouses across the city have been working with four crew members for years, and that no meaningful evidence exists that lives have been risked or lost.

Additionally, they note that the fire union that is now so vehemently objecting to reductions in the remaining engines agreed to the earlier reductions as part of bargaining on a contract in 1996.

Union officials say those negotiations were handled by different leadership, during a time of reorganization when the union was forced to make concessions.

The dispute is destined to go on, and a recent effort by firefighters to go to court to prevent the reductions is in danger of foundering after a Brooklyn judge last week ordered the union to post a multimillion-dollar bond to proceed with its action.

Still, the Kevin Kane fire offers a useful example for appreciating not only what firefighters do once they jump off the trucks that go screaming through the city streets every day, but also how few formal standards exist across the country for determining how many crew members are needed to safely battle fires.

While federal safety guidelines exist for protective gear and exposure to hazardous materials, staffing levels are left for cities to decide.

While Boston and Chicago already use four- and even three-member crews, that fact does not convince many New York firefighters that they could safely operate with the same number.

''America's fire is a one-story fire,'' said Vincent Dunn, who retired as a deputy chief from the Fire Department. ''That's where most people die. You look at Chicago, Philadelphia or Boston, where their poor live -- where fires happen -- and it's all two- and three-story row houses. But in New York City, our buildings are bigger. We have five- and six- and seven-story tenements, so our stretches are greater.''

It is the very act of stretching a hose line, the fundamental step in any firefighting effort, that is most hampered by a reduction in crew size, firefighters say. While ladder trucks ventilate fires and search for victims, an engine's function is to put out a blaze with a quick and steady force of water. The hose that must swiftly be put in place is cumbersome. It is pulled off the back of engines, dragged across sidewalks and hauled into buildings up often narrow and dark stairwells.

In a five-person engine company, there are five positions: the nozzle, backup, control, doorman and chauffeur (or driver) as they are called in New York. (There is also an officer leading each company, but that position is not included in the tally.)

At a fire, the nozzle, the backup and the control firefighters leap off the rig and begin carrying 50-foot lengths of hose into the building. The chauffeur opens the hydrant. The doorman opens the valves of the pump on the engine so that water can course through the line, and also helps carry up the hose line, checks it for kinks and feeds up additional lengths of hose.

The doorman is the fifth firefighter. In four-member companies that do not have a doorman, the control firefighter must stay outside to activate the engine's pump. There is one less set of hands to carry hose into the building, which can leave a company short when it comes to aggressively pushing into a fire, a quality that has distinguished the city's department nationally.

The department's official procedure with four-member engines is to send a second four-member engine company to assist with stretching the hose into a building.

But firefighters say this strategy is inefficient. They say that they often must wait critical minutes for the second engine to arrive, and that this goes against a central tenet of firefighting: early containment. They would be better served, they say, using a five-member crew on one hose line, rather than two four-member crews to move the same single line.

And they point to a 1987 department study that found that four-member crews took longer to stretch hose lines and tired twice as quickly as those with five members.

At the 1991 fire that killed Firefighter Kane, Engine 236 was, in fact, expected to help Engine Company 290 stretch its hose line into a burning apartment. But when Lt. Tony Variale of Engine 290 sized up the flames pouring out of the windows, he told Engine 236 not to assist his company, but to begin stretching its own line into a smoke-filled adjoining apartment.

''When I see that much fire, I need a backup line,'' recalled Mr. Variale, now a captain with Engine 24 in Greenwich Village. ''I mean, that's basic firefighting procedure. Because if there should be a problem with that first line, the second line is there to save you.''

It was not easy for either company to bring up its hose. The stairwell of the abandoned building was filled with furniture that squatters had dragged inside. A hole gaped in the stairs. The crews needed to drop extra hose line out a landing window -- an accepted practice, firefighters say -- so that more length would be available to press into back rooms, like the one that Firefighter Kane, a former paratrooper and the son of a retired assistant fire chief, entered.

But when the room suddenly filled with flames, Engine 236's hose was still hanging out the landing window. The company desperately tried to pull the hose line, but it was heavy with water and hard to pull without a doorman on the landing to help.

''I remember looking back and seeing this line like a Band-Aid, stretched,'' Captain Variale recalled.

Firefighters eventually succeeded in pulling up more hose and putting out the blaze. But those who heard Firefighter Kane's screams remain haunted by the thought that his death might have been prevented. Engine 236's control man, Greg Fagan, went on to Squad 1, which lost 12 men on Sept. 11, 2001, a fact that Mr. Fagan, now retired, recounted mournfully but dry-eyed in the garage of his Long Island home, surrounded by his Harley-Davidson motorcycles.

But when Mr. Fagan recalled Firefighter Kane's screams, his lower lip trembled and he wept. Mr. Fagan said he carried a profound sense of guilt for the death of Firefighter Kane. ''I remember everything about it,'' he said. ''I could still tell you the layout of the building.''

Captain Variale said a re-enactment soon after the fire showed that the 20 to 25 seconds that Firefighter Kane had been burned without water could have been cut to five to seven seconds if Engine 236 had had a fifth firefighter.

''If we were in a position to have pulled more hose, we could have saved him to a point where he wouldn't die,'' said Charlie LaSala, now retired, who was Engine 236's backup firefighter. ''It was a long, long hallway. You have to make turns, and it takes time to do that with a charged hose line in heavy smoke conditions. But we might have been there sooner to knock it down so he didn't burn so severely.''

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/06/02/...laze-91-comes-symbolize-dangers-cutbacks.html

FDNY REPORT ON FATAL FIRE SEPTEMBER 13, 1991

LADDER 110 LODD

FIREFIGHTER KEVIN C. KANE LADDER 110 SEPTEMBER 13, 1991

A Firefighter's Death as a Rallying Cry; Fatal Blaze in '91 Comes to Symbolize Dangers of Cutbacks

By Michelle O'Donnell

June 2, 2003

Shortly before dawn on Sept. 12, 1991, smoke poured from an apartment in an abandoned building in the East New York section of Brooklyn. At the apartment's entrance, firefighters with Ladder Company 110 passed members of Engine Company 236, who had directed their hose into the apartment.

Engine 236 was working with four instead of five firefighters because of staff reductions. As a result, the firefighter holding the nozzle of the hose cautioned the ladder company, Engine 236 did not have enough hose line on hand to reach the back room where the ladder team was headed.

But the search for victims could not wait, and the ladder company disappeared into the darkness. Moments later, a fiery section of the bedroom ceiling came crashing down on Firefighter Kevin Kane, 31. His screams anguished firefighters who tried, but failed, to make their way past the burning timbers.

Engine 236 rushed to pull up additional lengths of hose so that the stream of water could reach the back room. When Firefighter Kane leaped from a window minutes later into the bucket of a tower ladder, he had severe burns over 80 percent of his body. He died the next day.

To many firefighters, the 1991 fire has become known as the Kevin Kane fire, emblematic of the dangers of reducing engine staffing. Each time the city broaches the subject of formally reducing all engine crews to four members, as it has in recent months, the story of the Kevin Kane fire is retold in firehouses around the city.

But the story of the fire, like the issue it has come to symbolize, is complicated, deeply emotional and, in truth, not well understood.

The city, for instance, has always rebutted the claim that having one firefighter fewer in the crew of Engine 236 that day played a role in Firefighter Kane's death. Indeed, the question of how many firefighters can safely work in engine crews has been a thorny one for decades.

Firefighters say that, in one sense, no number of crew members can ensure complete safety. They believe that any reduction is reckless, and they argue that the move by the city in recent months to reduce the last 53 engines operating with five firefighters to four is intolerable.

City officials, including senior members of the Fire Department, have called such complaints little more than fear-mongering. They note emphatically that 150 engines operating out of firehouses across the city have been working with four crew members for years, and that no meaningful evidence exists that lives have been risked or lost.

Additionally, they note that the fire union that is now so vehemently objecting to reductions in the remaining engines agreed to the earlier reductions as part of bargaining on a contract in 1996.

Union officials say those negotiations were handled by different leadership, during a time of reorganization when the union was forced to make concessions.

The dispute is destined to go on, and a recent effort by firefighters to go to court to prevent the reductions is in danger of foundering after a Brooklyn judge last week ordered the union to post a multimillion-dollar bond to proceed with its action.

Still, the Kevin Kane fire offers a useful example for appreciating not only what firefighters do once they jump off the trucks that go screaming through the city streets every day, but also how few formal standards exist across the country for determining how many crew members are needed to safely battle fires.

While federal safety guidelines exist for protective gear and exposure to hazardous materials, staffing levels are left for cities to decide.

While Boston and Chicago already use four- and even three-member crews, that fact does not convince many New York firefighters that they could safely operate with the same number.

''America's fire is a one-story fire,'' said Vincent Dunn, who retired as a deputy chief from the Fire Department. ''That's where most people die. You look at Chicago, Philadelphia or Boston, where their poor live -- where fires happen -- and it's all two- and three-story row houses. But in New York City, our buildings are bigger. We have five- and six- and seven-story tenements, so our stretches are greater.''

It is the very act of stretching a hose line, the fundamental step in any firefighting effort, that is most hampered by a reduction in crew size, firefighters say. While ladder trucks ventilate fires and search for victims, an engine's function is to put out a blaze with a quick and steady force of water. The hose that must swiftly be put in place is cumbersome. It is pulled off the back of engines, dragged across sidewalks and hauled into buildings up often narrow and dark stairwells.

In a five-person engine company, there are five positions: the nozzle, backup, control, doorman and chauffeur (or driver) as they are called in New York. (There is also an officer leading each company, but that position is not included in the tally.)

At a fire, the nozzle, the backup and the control firefighters leap off the rig and begin carrying 50-foot lengths of hose into the building. The chauffeur opens the hydrant. The doorman opens the valves of the pump on the engine so that water can course through the line, and also helps carry up the hose line, checks it for kinks and feeds up additional lengths of hose.

The doorman is the fifth firefighter. In four-member companies that do not have a doorman, the control firefighter must stay outside to activate the engine's pump. There is one less set of hands to carry hose into the building, which can leave a company short when it comes to aggressively pushing into a fire, a quality that has distinguished the city's department nationally.

The department's official procedure with four-member engines is to send a second four-member engine company to assist with stretching the hose into a building.

But firefighters say this strategy is inefficient. They say that they often must wait critical minutes for the second engine to arrive, and that this goes against a central tenet of firefighting: early containment. They would be better served, they say, using a five-member crew on one hose line, rather than two four-member crews to move the same single line.

And they point to a 1987 department study that found that four-member crews took longer to stretch hose lines and tired twice as quickly as those with five members.

At the 1991 fire that killed Firefighter Kane, Engine 236 was, in fact, expected to help Engine Company 290 stretch its hose line into a burning apartment. But when Lt. Tony Variale of Engine 290 sized up the flames pouring out of the windows, he told Engine 236 not to assist his company, but to begin stretching its own line into a smoke-filled adjoining apartment.

''When I see that much fire, I need a backup line,'' recalled Mr. Variale, now a captain with Engine 24 in Greenwich Village. ''I mean, that's basic firefighting procedure. Because if there should be a problem with that first line, the second line is there to save you.''

It was not easy for either company to bring up its hose. The stairwell of the abandoned building was filled with furniture that squatters had dragged inside. A hole gaped in the stairs. The crews needed to drop extra hose line out a landing window -- an accepted practice, firefighters say -- so that more length would be available to press into back rooms, like the one that Firefighter Kane, a former paratrooper and the son of a retired assistant fire chief, entered.

But when the room suddenly filled with flames, Engine 236's hose was still hanging out the landing window. The company desperately tried to pull the hose line, but it was heavy with water and hard to pull without a doorman on the landing to help.

''I remember looking back and seeing this line like a Band-Aid, stretched,'' Captain Variale recalled.

Firefighters eventually succeeded in pulling up more hose and putting out the blaze. But those who heard Firefighter Kane's screams remain haunted by the thought that his death might have been prevented. Engine 236's control man, Greg Fagan, went on to Squad 1, which lost 12 men on Sept. 11, 2001, a fact that Mr. Fagan, now retired, recounted mournfully but dry-eyed in the garage of his Long Island home, surrounded by his Harley-Davidson motorcycles.

But when Mr. Fagan recalled Firefighter Kane's screams, his lower lip trembled and he wept. Mr. Fagan said he carried a profound sense of guilt for the death of Firefighter Kane. ''I remember everything about it,'' he said. ''I could still tell you the layout of the building.''

Captain Variale said a re-enactment soon after the fire showed that the 20 to 25 seconds that Firefighter Kane had been burned without water could have been cut to five to seven seconds if Engine 236 had had a fifth firefighter.

''If we were in a position to have pulled more hose, we could have saved him to a point where he wouldn't die,'' said Charlie LaSala, now retired, who was Engine 236's backup firefighter. ''It was a long, long hallway. You have to make turns, and it takes time to do that with a charged hose line in heavy smoke conditions. But we might have been there sooner to knock it down so he didn't burn so severely.''

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/06/02/...laze-91-comes-symbolize-dangers-cutbacks.html

FDNY REPORT ON FATAL FIRE SEPTEMBER 13, 1991

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

LADDER 110 LODD

LIEUTENANT PAUL MITCHELL LADDER 110 SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

Paul Mitchell, 46, fire lieutenant affectionately called 'Big Daddy'

By Staten Island Advance

Date of Death 9/11/2001

By Michael J. Paquette

Advance staff writer

Tuesday, 10/30/2001

STATEN ISLAND, N.Y. — The firefighters at Ladder Co. 110 looked up to "Big Daddy," and it wasn't only because of his towering physique.

Lt. Paul Mitchell was also a respected leader, a strong man with a caring and generous spirit.

He took probies under his wing, offering tips on safety and preparedness. And he gave guidance to all who asked, dispensing counsel on everything from golfing to how to get grants to pay for a kid's education.

Everybody relied on "Big Daddy."

"Even chiefs came to him for advice. Paul had an answer for everything," said Firefighter Christopher Gunn, Mr. Mitchell's longtime friend at Brooklyn's Ladder Co. 110. "Just like with his family, he was Superman to them. Well, he was Superman to us. That's how we looked up to him."

Early on the morning of Sept. 11, Mr. Mitchell was ending a 24-hour shift at Engine Co. 5 in Manhattan, where he had been temporarily assigned.

He was heading home to Annadale when the first plane hit the World Trade Center sometime during the trip down the FDR Drive, and he quickly made his way to Ladder Co. 110 on Tillary Street, where he began his firefighting career in 1987.

"It was his home. He was always there," said his wife, the former Maureen Brown. "He was a very large presence on Tillary Street."

By the time Mr. Mitchell arrived at the Brooklyn firehouse, his brothers had already left for Lower Manhattan, so he grabbed some gear and hopped in a Fire Department van that followed a chief's car to the scene. He was last seen near Tower 2.

Mr. Mitchell remains among the thousands missing in the terrorist attacks. He was 46.

"He just loved being a fireman," said Mrs. Mitchell. "He wanted a job where he could help people and do something worthwhile."

Mr. Mitchell, who stood 6 feet 4 inches tall, earned the name "Big Daddy" at Ladder Co. 110, where he spent most of his Fire Department career until he was promoted to lieutenant last October and assigned to Manhattan's 1st Battalion. As with all first-year lieutenants, he covered shifts where needed throughout the city. But his heart was always stationed at Tillary Street.

"His last run was that run (on Sept. 11), and he left from our quarters," said Mr. Gunn. "It's not coincidence that that's where he left from. It was meant to be."

Mr. Mitchell was born in Brooklyn, and taken to Meiers Corners as a child. He graduated from St. Peter's Boys High School. In 1978, he settled in Annadale. For 11 years, he worked as a dock foreman at General Motors in Linden, N.J., but found his calling in the FDNY.

"You could tell that the job and the man were made for each other," said Gary Barton of Bulls Head, Mr. Mitchell's close friend for the past decade.

"He considered the firemen his family," said Mrs. Mitchell, a third- and fourth-grade special education teacher at PS 30 in Westerleigh. "We went on vacation with other firemen every summer. He ran the golf outing. He ran the annual dinner-dance. He was a leader."

Mr. Mitchell was an avid golfer, and served as assistant golf coach at Notre Dame Academy while his daughter, Jennifer, an Advance All-Star, was a student there.

He was a parishioner of Our Lady Star of the Sea R.C. Church, Huguenot, and coached girls' basketball and soccer at the parish school, beginning when his daughters were students there.

"Even after my girls graduated from there, he coached basketball there," said Mrs. Mitchell. "He used to help the girls, particularly at Notre Dame. He used to encourage them to go to regional tournaments."

Mr. Mitchell was "extremely proud" of his daughters' academic and sports' accomplishments, his wife said.

His younger daughter, Christine, was an Advance All-Star in volleyball. Both young women now attend Boston College. Jennifer is a 20-year-old junior and a valued member of the golf team. Christine, 18, is a freshman who recently decided to serve as a Eucharistic minister at school.

Jennifer and Christine last saw their dad the week before Sept. 11, when their parents drove them to Boston and Mr. Mitchell helped build bookcases for their rooms.

But Mr. Mitchell's reputation for helping others extended well beyond his family and friends to neighbors, acquaintances and strangers.

A skilled woodworker, he enjoyed making plaques for firefighters when they were promoted or retired, and one of his biggest thrills was hosting a "pasta night" for local firefighters during the couple's annual retreat to Cape Cod.

"Everybody loved him. He was always helping people. He was always extending himself for people, going out of his way," said Mrs. Mitchell. "He made people feel very warm and comfortable. So many people have been touched by him."

"Never, in all my years of knowing Paul, did I ever hear him say no to anybody," Mr. Barton said. "If you needed a hand, somehow Big Daddy was always there." In addition to his wife, Maureen, and his daughters, Jennifer and Christine, survivors include his mother, Rosemary, and his sisters, Marie Mitchell and Susan McCormick.

A memorial mass is scheduled for Friday at 11 a.m. in Our Lady Star of the Sea Church.

https://www.silive.com/september-11/2010/09/paul_mitchell_46_fire_lieutena.html

ROLL OF HONOR

Paul Thomas Mitchell

Lieutenant

Fire Department City of New York

New York

Age: 46

Year of Death: 2001

Husband of Maureen. Father of two daughters (Jennifer age 20 and Christine age 18) 46 years old at time of death

Community Involvement – Coach of Girls Soccer for eight years‚ Girls Basketball Coach for eight years‚ HS Golf Coach for four years

Received three prior citations for valor

15 years with FDNY

He is also survived by his mother‚ Rosemary Mitchell and sisters‚ Susan McCormick and Marie Mitchell

https://katv.com/archive/remembering-911-widow-of-nyc-firefighter-shares-story

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

LADDER 110 LODD

LIEUTENANT PAUL MITCHELL LADDER 110 SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

Paul Mitchell, 46, fire lieutenant affectionately called 'Big Daddy'

By Staten Island Advance

Date of Death 9/11/2001

By Michael J. Paquette

Advance staff writer

Tuesday, 10/30/2001

STATEN ISLAND, N.Y. — The firefighters at Ladder Co. 110 looked up to "Big Daddy," and it wasn't only because of his towering physique.

Lt. Paul Mitchell was also a respected leader, a strong man with a caring and generous spirit.

He took probies under his wing, offering tips on safety and preparedness. And he gave guidance to all who asked, dispensing counsel on everything from golfing to how to get grants to pay for a kid's education.

Everybody relied on "Big Daddy."

"Even chiefs came to him for advice. Paul had an answer for everything," said Firefighter Christopher Gunn, Mr. Mitchell's longtime friend at Brooklyn's Ladder Co. 110. "Just like with his family, he was Superman to them. Well, he was Superman to us. That's how we looked up to him."

Early on the morning of Sept. 11, Mr. Mitchell was ending a 24-hour shift at Engine Co. 5 in Manhattan, where he had been temporarily assigned.

He was heading home to Annadale when the first plane hit the World Trade Center sometime during the trip down the FDR Drive, and he quickly made his way to Ladder Co. 110 on Tillary Street, where he began his firefighting career in 1987.

"It was his home. He was always there," said his wife, the former Maureen Brown. "He was a very large presence on Tillary Street."

By the time Mr. Mitchell arrived at the Brooklyn firehouse, his brothers had already left for Lower Manhattan, so he grabbed some gear and hopped in a Fire Department van that followed a chief's car to the scene. He was last seen near Tower 2.

Mr. Mitchell remains among the thousands missing in the terrorist attacks. He was 46.

"He just loved being a fireman," said Mrs. Mitchell. "He wanted a job where he could help people and do something worthwhile."

Mr. Mitchell, who stood 6 feet 4 inches tall, earned the name "Big Daddy" at Ladder Co. 110, where he spent most of his Fire Department career until he was promoted to lieutenant last October and assigned to Manhattan's 1st Battalion. As with all first-year lieutenants, he covered shifts where needed throughout the city. But his heart was always stationed at Tillary Street.

"His last run was that run (on Sept. 11), and he left from our quarters," said Mr. Gunn. "It's not coincidence that that's where he left from. It was meant to be."

Mr. Mitchell was born in Brooklyn, and taken to Meiers Corners as a child. He graduated from St. Peter's Boys High School. In 1978, he settled in Annadale. For 11 years, he worked as a dock foreman at General Motors in Linden, N.J., but found his calling in the FDNY.

"You could tell that the job and the man were made for each other," said Gary Barton of Bulls Head, Mr. Mitchell's close friend for the past decade.

"He considered the firemen his family," said Mrs. Mitchell, a third- and fourth-grade special education teacher at PS 30 in Westerleigh. "We went on vacation with other firemen every summer. He ran the golf outing. He ran the annual dinner-dance. He was a leader."

Mr. Mitchell was an avid golfer, and served as assistant golf coach at Notre Dame Academy while his daughter, Jennifer, an Advance All-Star, was a student there.

He was a parishioner of Our Lady Star of the Sea R.C. Church, Huguenot, and coached girls' basketball and soccer at the parish school, beginning when his daughters were students there.

"Even after my girls graduated from there, he coached basketball there," said Mrs. Mitchell. "He used to help the girls, particularly at Notre Dame. He used to encourage them to go to regional tournaments."

Mr. Mitchell was "extremely proud" of his daughters' academic and sports' accomplishments, his wife said.

His younger daughter, Christine, was an Advance All-Star in volleyball. Both young women now attend Boston College. Jennifer is a 20-year-old junior and a valued member of the golf team. Christine, 18, is a freshman who recently decided to serve as a Eucharistic minister at school.

Jennifer and Christine last saw their dad the week before Sept. 11, when their parents drove them to Boston and Mr. Mitchell helped build bookcases for their rooms.

But Mr. Mitchell's reputation for helping others extended well beyond his family and friends to neighbors, acquaintances and strangers.

A skilled woodworker, he enjoyed making plaques for firefighters when they were promoted or retired, and one of his biggest thrills was hosting a "pasta night" for local firefighters during the couple's annual retreat to Cape Cod.

"Everybody loved him. He was always helping people. He was always extending himself for people, going out of his way," said Mrs. Mitchell. "He made people feel very warm and comfortable. So many people have been touched by him."

"Never, in all my years of knowing Paul, did I ever hear him say no to anybody," Mr. Barton said. "If you needed a hand, somehow Big Daddy was always there." In addition to his wife, Maureen, and his daughters, Jennifer and Christine, survivors include his mother, Rosemary, and his sisters, Marie Mitchell and Susan McCormick.

A memorial mass is scheduled for Friday at 11 a.m. in Our Lady Star of the Sea Church.

https://www.silive.com/september-11/2010/09/paul_mitchell_46_fire_lieutena.html

ROLL OF HONOR

Paul Thomas Mitchell

Lieutenant

Fire Department City of New York

New York

Age: 46

Year of Death: 2001

Husband of Maureen. Father of two daughters (Jennifer age 20 and Christine age 18) 46 years old at time of death

Community Involvement – Coach of Girls Soccer for eight years‚ Girls Basketball Coach for eight years‚ HS Golf Coach for four years

Received three prior citations for valor

15 years with FDNY

He is also survived by his mother‚ Rosemary Mitchell and sisters‚ Susan McCormick and Marie Mitchell

https://katv.com/archive/remembering-911-widow-of-nyc-firefighter-shares-story

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

Last edited:

ENGINE 207/LADDER 110/SATELLITE 6/BATTALION 31/DIVISION 11 (CONTINUED)

ENGINE 207 LODD

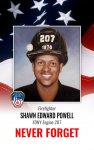

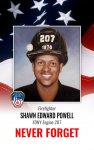

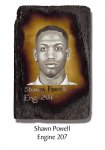

FIREFIGHTER SHAWN POWELL ENGINE 207 SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

His Glass Was Full

Shawn E. Powell was the firefighter with the light touch. Whether working at Engine Company 207 in downtown Brooklyn, at home in Crown Heights, or camping with his 5- year-old son, Joshua, he had a way of lifting spirits. "If there wasn't any fun going on, he would find a way," said Matthew Dwyer, a fellow firefighter. "With Shawn, the glass was half full, never half empty."

Firefighter Powell, 32, brought unusual skills to the Fire Department. An artist and woodcarver, he had built props and volunteered at several New York City theaters, including the Apollo Theater, and studied architecture at New York Technical College.

At Engine Company 207 — where the slogan is "The House of Misfit Toys" because of the company's specialized, somewhat bizarre-looking fire-fighting equipment — Mr. Powell made the point in comic relief with a poster that includes a square- wheeled fire engine.

Firefighter Powell and his wife, Jean, who had been teenage sweethearts in Brooklyn, married in 1989 and moved immediately to Germany, where he served four years in the Army.

This year, Firefighter Powell's passion had been camping with Joshua.

On several trips to lakes and state parks in New Jersey, he was teaching the boy to make a campfire and put up a tent and had planned another father-son outing soon after Sept. 11.

https://obits.lohud.com/obituaries/lohud/obituary.aspx?n=shawn-edward-powell&pid=146402

Our 9/11 Bravest ॥ Never Forget

Today is the birthday of FDNY firefighter Shawn Powell. He was born on June 28, 1969 and would have been 51 years old today. We will never forget the ultimate sacrifice that he made on September 11, 2001.

To the Powell family: Shawn and I were in the same FDNY Academy Class (class 3 of '96). We both were from Brooklyn, so we often drove to The Rock together. We shared a love of music, motorcycles, and life. Shawn's memorial service was the most touching one I attended, everyone came- even his scoutmasters. Shawn was/is Christlike: Strong and quiet, with dignity and grace beaming from that big beautiful smile. I miss him. - Christopher Connor, Brooklyn, NY

Shawn is one of my closest friends, and I say "is" because he will always be with me in my heart. In a group of great men shawn stood out as the greatest, someone you could always count on, always there for you. I have fond memories of the camping trips we would go on. The nicest guy you could ever meet. I send my deepest sympathy to Jean, Joshua and the Powell family. We love you Shawn. Skiter Freeman, New York, NY

I have SGT Powell's picture hanging in my classroom next to the US flag at Hillcrest High School as a constant reminder of his sacrifice. I thank him and you, his family, for all he accomplished. It is a comfort to be serving in the US Army in Germany in response to this tragedy. Once again, my sincere sympathy, and may God bless you and comfort you.

SSG James G Sylvester, Huntington Station, NY

My condolences to the Powell Family. I had the pleasure of knowing a great individual. Shawn and I lived on the same block Monroe St. and attended P. S. 308. Shawn was a people person and loved helping others. He always put himself last. I am glad to know that he was able to do what he loved. I know that you are in heaven looking down and smiling at us. Shawn's smile could brighten any and every day of all the people's life's that he touched. . My prayers are and will always be with the family. GOD BLESS. Michele Malloy, Lithonia, GA

Shawn and I served in the same Army Reserve Unit, the 343rd Combat Support Hospital, for several years. He was always a good friend, at work and at home. Engine 207 serves my neighborhood so sometimes I would hear him calling out as I ran by the station house or as their truck drove by. I have a memorial card from his service on my refrigerator, so his smile greets me constantly. The motto for the 343rd was "The Best of the Best". HE WAS. SGT Invera Woodson-Tabor, Brooklyn, NY

Shawn was a member of my Army Reserve Unit, and was never without a smile for someone. I attended the memorial service where Shawn was honored and the love of Shawn, by family friends and members of his reserve unit, demonstrated how much he is loved. We will always remember that wonderful smile you had for us all. COL Patricia Affe, 4220th USAH - Shoreham, NY

Sergeant Shawn Powell, who had thirteen years of military service, was a firefighter assigned to Engine Company 207 in Brooklyn. Sergeant Powell served four years on active duty with the Army before joining the Army Reserve. He completed the combat medic course and emergency medical technician course, and was serving as a medical assistant at the 4220th U.S.

Army Hospital.

RIP. NEVER FORGET.

ENGINE 207 LODD

FIREFIGHTER SHAWN POWELL ENGINE 207 SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

His Glass Was Full

Shawn E. Powell was the firefighter with the light touch. Whether working at Engine Company 207 in downtown Brooklyn, at home in Crown Heights, or camping with his 5- year-old son, Joshua, he had a way of lifting spirits. "If there wasn't any fun going on, he would find a way," said Matthew Dwyer, a fellow firefighter. "With Shawn, the glass was half full, never half empty."

Firefighter Powell, 32, brought unusual skills to the Fire Department. An artist and woodcarver, he had built props and volunteered at several New York City theaters, including the Apollo Theater, and studied architecture at New York Technical College.

At Engine Company 207 — where the slogan is "The House of Misfit Toys" because of the company's specialized, somewhat bizarre-looking fire-fighting equipment — Mr. Powell made the point in comic relief with a poster that includes a square- wheeled fire engine.

Firefighter Powell and his wife, Jean, who had been teenage sweethearts in Brooklyn, married in 1989 and moved immediately to Germany, where he served four years in the Army.

This year, Firefighter Powell's passion had been camping with Joshua.

On several trips to lakes and state parks in New Jersey, he was teaching the boy to make a campfire and put up a tent and had planned another father-son outing soon after Sept. 11.

https://obits.lohud.com/obituaries/lohud/obituary.aspx?n=shawn-edward-powell&pid=146402

Our 9/11 Bravest ॥ Never Forget

Today is the birthday of FDNY firefighter Shawn Powell. He was born on June 28, 1969 and would have been 51 years old today. We will never forget the ultimate sacrifice that he made on September 11, 2001.

To the Powell family: Shawn and I were in the same FDNY Academy Class (class 3 of '96). We both were from Brooklyn, so we often drove to The Rock together. We shared a love of music, motorcycles, and life. Shawn's memorial service was the most touching one I attended, everyone came- even his scoutmasters. Shawn was/is Christlike: Strong and quiet, with dignity and grace beaming from that big beautiful smile. I miss him. - Christopher Connor, Brooklyn, NY

Shawn is one of my closest friends, and I say "is" because he will always be with me in my heart. In a group of great men shawn stood out as the greatest, someone you could always count on, always there for you. I have fond memories of the camping trips we would go on. The nicest guy you could ever meet. I send my deepest sympathy to Jean, Joshua and the Powell family. We love you Shawn. Skiter Freeman, New York, NY

I have SGT Powell's picture hanging in my classroom next to the US flag at Hillcrest High School as a constant reminder of his sacrifice. I thank him and you, his family, for all he accomplished. It is a comfort to be serving in the US Army in Germany in response to this tragedy. Once again, my sincere sympathy, and may God bless you and comfort you.

SSG James G Sylvester, Huntington Station, NY

My condolences to the Powell Family. I had the pleasure of knowing a great individual. Shawn and I lived on the same block Monroe St. and attended P. S. 308. Shawn was a people person and loved helping others. He always put himself last. I am glad to know that he was able to do what he loved. I know that you are in heaven looking down and smiling at us. Shawn's smile could brighten any and every day of all the people's life's that he touched. . My prayers are and will always be with the family. GOD BLESS. Michele Malloy, Lithonia, GA