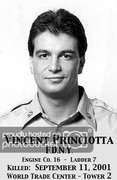

Engine 16/Ladder 7 (continued)

Engine 16 history:

Wednesday, October 11, 2017 Engine Company 16 - 223 East 25th Street - Daytonian in Manhattan

When the loose network of volunteer fire companies was disbanded in 1865 as the professional Metropolitan District fire department was formed, it was a melancholy day for many of the veteran "laddies." Among the 41 members of the Lexington Engine Company, No. 7 were a barber, two butchers, a ship-joiner, a horse shoer, and a carriage maker. On September 18, 1865 the fire department announced that their old fire house at No. 223 East 25th Street would become home to the newly-formed Metropolitan Steam Fire Engine Company No. 16.

When Engine Company 16 took over the building the Kips Bay area was still relatively undeveloped. But the flurry of construction in the first years following the Civil War brought tenements, stores and small factory buildings. In the early 1880s the fire department was scrambling to build new firehouses and update or replace the old ones to keep up with the expanding city.

In 1879 Napoleon Le Brun had become the official architect for the fire department. The following year his son, Pierre, joined him to create N. Le Brun & Son. The firm filed plans on August 1, 1882 for a replacement fire house for Engine Company 16. The three-story structure was projected to cost $18,000, or in the neighborhood of $436,000 today.

The completed structure followed the typical fire house pattern. The cast iron base was dominated by the central truck bay. The two upper floors were clad in red brick. As was often the case with their less opulent fire houses, N. Le Brun & Son relied on terra cotta and creative brickwork for decorative effect. A knobby quilt of terra cotta tiles filled the spandrels above the second and third floors, and the dog-tooth pattern brick filled the arches of the top floor openings. Above a frieze of floral terra cotta tiles was an unusually deep bracketed cast metal cornice.

As with all fire companies, No. 16 responded to an array of calls. The fire on the night of July 10, 1899 was especially memorable. It broke out in the Infants' Pavilion of Bellevue Hospital, described by The New York Times as "ramshackle."

Around 11:00 Miss Abbe, the head of the four nurses in the ward, entered the darkened room to check on a sick baby. The hospital's location near the East River and the summer heat necessitated the cribs being covered in mosquito netting. While Miss Abbe tended to the baby, her candle fell over setting fire to the netting.

The Times reported "With a puff the whole netting burst into flames. The blaze jumped to either side, ran along from crib to crib, and caught the bed linen. Miss Abbe stood her ground heroically and pulled at the blazing material until her hands were seriously burned."

By the time Engine Company 16 could respond the fire had spread to the adult wards. Here, too, the mosquito netting quickly caught fire and a civilian, Albert Stone who was a former fireman, rushed in to help, tearing down the netting as Engine Company 16 attacked the flames. Unfortunately some of the patients were burned. The Times reported "The injury to the patients may be serious."

The work of fire fighters, by nature, put their lives at risk. On May 3, 1903 Engine Company 16 responded to a fire in the four-story boarding house at First Avenue and 15th Street. When the truck arrived 50-year old Henry Williams was trapped on the upper floor and flames could be seen in his room from the street.

Twenty-four year old William McNally scaled a ladder to the window. The New-York Tribune reported "As McNally got to the top a sheet of flame burst out of the window." The fire fighter paused, then jumped inside. A few moments later he appeared with McWilliams in his arms. The crowd watching from the sidewalk broke into cheers.

Their jubilation was soon crushed. Just as McNally started to climb out of the window, he was overcome and both he and McWilliams fell back into the burning room as "another sheet of flame leaped from the window."

Firefighter James C. McEvoy clambered up the ladder. He reappeared in the window with McNally, half conscious, whom he managed to get to the ground. Now Engine Company 16's foreman, McGarrity, and firefighter Lang headed up for the other victim. They found McWilliams unconscious and dragged him to another window where there was a fire escape. On the way down, McGarrity's foot got wedged in a triangular space of the fire escape. Lang continued down with McWilliams while McGarrity struggled to escape as the flames closed in.

By the time firefighters freed his foot by using crowbars and hammers it was too late. McWilliams died on the way to Bellevue Hospital. Both McNally and McEvoy suffered severe burns.

McWilliams's widow would receive half his salary as a pension. But the following year there was a question about whether Mark Kelly's widow would receive the same compensation.

On February 7, 1904 fire broke out in the western part of downtown Baltimore. It quickly outstripped the abilities of the Baltimore Fire Department and calls for help were sent out to other cities. New York's Acting Fire Chief Kruger received a telephone call saying "that Baltimore's men were worn out and needed all the help they could get," according to the New-York Tribune.

Before dawn the following morning nine engines and a hook and ladder truck along with 105 firemen, including the men of Engine Company 16 headed south. The Tribune noted "It was the first time within the memory of old firemen when the department had been called on to send the fire fighters so far outside the city."

Battalion Chief Howe telegraphed Chief Kruger at 5:30 a.m. on February 9 saying "We are now combating the fire on the water front. All our firemen are in good condition and working hard."

Among those men was Engineer Mark Kelly, of Engine Company 16. The frigid February winds off the Baltimore harbor made the work even more grueling. The Evening World later pointed out "He had been on constant duty for twenty-two hours without being relieved at the Baltimore fire."

The inferno was finally extinguished; but not before 1,500 buildings and some 140 acres of Baltimore were destroyed. The men of Engine Company 16 returned home on the night of February 9. When they arrived Kelly was so ill he had to be helped home. He had contracted pneumonia due to exposure.

Kelly was already a hero who had distinguished himself in more than two dozen fires and was credited for saving several lives. His condition did not improve and on February 26, 1904 The Evening World ran the headline: NOTED FIRE HERO MARTYR TO DUTY.

Kelly received an impressive department funeral. But then his comrades turned their attention to his pension. Widows of firefighters who died of natural causes were eligible to $25 a month, as opposed to the one-half salary for line of duty deaths. Kelly earned $1,600 a year so the difference to his widow and three children would be significant.

The Times reported "Kelly's fellow-firemen believe that the widow will be allowed half his salary as a pension, since the disease he contracted was a direct result o his exposure while performing his duty." The nation responded as well, The Insurance Times noting "Few public funds created more sympathy or support than did that raised for the widow of the brave New York fireman, Mark Kelly, who lost his life through his hard work in connection with the Baltimore fire."

In July 1906 the department's architect Alexander Stevens filed plans to renovations to the 25th Street station house, including "new reinforced concrete floors and installing iron staircases." The $15,000 improvements were intended "to increase the floor stability."

The heavy engine of Company 16 was pulled by three strong horses. The firefighters riding on the front of the vehicle were expected to use what today would be called seat belts. The importance of the safety feature became tragically obvious on the afternoon of March 28, 1910.

Fireman Joseph White was the driver that afternoon when the company responded to a grocery store fire on First Avenue. In his haste, White failed to strap himself in. The engine headed east, but "when the wheels struck a deep rut at First avenue and 23d street White was pitched forward to the pavement between two of the three galloping horses and then crushed under the wheels of the engine." The horses galloped on until a group of civilians were able to bring them to a halt.

White never regained consciousness and died within ten minutes. Ironically, the fire, described by the New-York Tribune as "a trifling affair," caused a mere $25 in damages.

The rules of the Fire Department expressly prohibited drinking alcohol while on duty. Fireman Walter J. Hicks cleverly devised a way around the rules--for a while, anyway. His undoing cam when Captain Martin Morrison was talking to Assistant Foreman Slowey outside the fire house on August 10, 1911. They noticed a small boy with a can "such as is generally used to carry beer from saloons," as explained by The Times, go into the house next door to the station.

The newspaper reported that Morrison's suspicions were raised and he sneaked up to the top floor of the fire house with Slowey as a witness, "but stopped on the stairs when his head was on a level with the floor." Peeking through the banisters, he saw Hicks staring at the skylight. Suddenly the skylight opened and the can of beer was lowered down on a cord. "Hicks grasped it and drank its contents with signs of great satisfaction."

Morrison and Slowey quietly went downstairs, but returned later for the evidence. They confronted the imbibing firefighter who said he "knew nothing about the can." Nevertheless, The Times explained "the evidence was so strong against him that he was required to give up five day's pay."

The company's motorized truck can be glimpsed through the open bay doors around 1935. photographer unknown, from the collection of the Columbia University Libraries, Information Services:

Engine Company 16's horses had been replaced by a motorized truck by 1924, when the city was plagued by an arsonist. When they arrived at a blaze at 23rd Street and Second Avenue at 4:40 on the morning of August 20, it was the latest in more than 100 fires had been purposely set. The man leaning against the fire alarm box post at that hour of the morning raised the suspicions of Fire Captain Amanuel Goldsmith. He detained him, then turned him over to Patrolman Murphy.

The young man would not answer the question as to whether he had set the fire. Instead he rambled on about himself, saying his name was Kenneth Karick and was a horse trainer and former jockey. While he claimed he had just arrived from Saratoga "with a large sum of money," he had no cash on him "and was unable to tell them what had become of it," according to newspaper accounts.

After much questioning, he finally confessed. His name was actually George C. Custow, and he told a judge he had "an uncontrollable impulse to set fires" and that he "got a wonderful thrill" watching the firemen and fire apparatus. The 26-year old's father blamed his "aberrations" on "an attack of infantile paralysis which left him a cripple in 1916."

By the 1960s the old fire house was inadequate for modern equipment. In 1968 Engine Company 16 moved into the newly-built fire house at No. 234 East 29th Street with Hook and Ladder Company 7.

Five years later the city announced the 25th Street fire house would be sold at auction, with an opening bid of $24,000. The 500 bidders quickly drove the price up, until the Ninth Church of Christ, Scientist won it with a bid of $217,000. Even the city's Department of Real Estate was surprised, a spokesman saying "we never thought it would go as high as it did."

The second floor was slightly remodeled for worship space, leaving the original pressed tin ceiling intact. On the top floor one can envision Captain Morrison peeking through the banisters at a beer-drinking fireman. photographs via www.elliman.com

The church made expected renovations to the building, removing the truck bay doors and remodeling the interiors. The group remained in the building until 2017 when it offered the property for $7.3 million.

-http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2017/10/engine-company-16-223-east-25th-street.html

Ladder 7 history:

Napoleon Le Brun's Hook & Ladder No. 7 - 217 East 28th Street - Daytonian in Manhattan

The Washington Hook and Ladder 9 operated from its firehouse at No. 217 East 28th Street prior to 1865. One of many volunteer companies scattered throughout the city, its members were volunteers who lived in the neighborhood. When a fire broke out, the men called "laddies" would scramble to the firehouse. Fire companies often vied with one another to arrive at the fire first, or to become more skilled at extinguishing blazes.

The end of the disorganized system came following the devastating fire that destroyed Barnum's Museum in 1865. The State Assembly passed the Act of 1865 that coupled Brooklyn and New York with a professional "Metropolitan District" fire department. Washington Hook and Ladder 9 was replaced on October 11, 1865 by Hook and Ladder Company No. 7.

Fighting fires in the crowded city was made more dangerous and difficult because of the highly flammable materials that were so often involved. Houses and apartment buildings were lit either by kerosene lamps or gas; carriage houses and stables were filled with hay and grain; and distilleries, pharmacies and printing houses stored explosive components.

An example was the devastating blaze that broke out in Walter Briggs's large livery and boarding stable on February 13, 1879. The New York Herald's headline read "Insatiate Flames" and the article noted "A large quantity of hay and straw was known to be stored near the very spot from which the flames were issuing."

The firefighters' valiant efforts were split between extinguishing the inferno and to saving the horses. There were, in addition, dozens of expensive carriages and sleighs stored on the various levels of the structure. Three firefighters were injured, one of them Washington Ryer who was briefly buried when the roof caved in.

Tragically, while the firefighters managed to save the building from complete destruction, 70 horses, some of them quite valuable, were lost.

The same year of the Brigg's stable fire Napoleon LeBrun was appointed official architect for the New York City Fire Department. A year later, after his son Pierre joined him, his firm became N. LeBrun & Son. By 1895 when he stepped down, he and his son would be responsible for designing 42 fire department structures.

Among their last jobs was the refurbishing of Hook and Ladder 7's firehouse in 1893. The remodeling was so extensive that the Fire Departments 1894 report called it a "new building, rebuilt for Hook and Ladder Company No. 7."

The result was signature LeBrun. The stone-clad base followed the expected firehouse arrangement--a centered truck bay flanked by a doorway and window. The sparse decoration at this level relied on two carved shields with flowing ribbons below the dentiled cornice.

The upper two stories were faced in variegated Roman brick trimmed in limestone. A common feature in LeBrun designs was the central plaque, inscribed with pertinent construction information (the mayor, commissioner, etc.), flanked by decorative rondels that announced the date. Splayed lintels above the second floor windows and voussoirs above the third were executed in brick and enhanced with scrolled keystones. The pressed metal cornice featured an intricate frieze and a double row of brackets, the topmost of which terminated in lions' heads.

The members of Hook and Ladder No. 7 had scarcely settled into the refurbished firehouse before a frightening blaze broke out in a tenement house at No. 74 Pearl Street on the night of January 2, 1894. Fireman John P. Howe jumped from the moving truck and ran ahead to rescue the tenants.

John P. Howe was one of many members of the Company who earned medals for bravery. The Evening World, May 24, 1895.

The Evening World reported "While carrying out Bridget Maloney an invalid, his hands and face were burned, but notwithstanding this Howe returned and saved Mrs. Eliza Keenan and her daughter Lillie."

Howe was involved in a nearly unbelievable act of heroism exactly two years later to the day. Fire erupted in the Geneva Club on Lexington Avenue, an organization of hotel employees. Several members lived in the upper floors of the three-story building.

John Howe was driving the truck and as he pulled up to the scene, according to the New-York Tribune, "There were faces at the windows of the upper floors where the occupants had been cut off from escape to the street. The lower rooms were all aflame."

The article noted "The spirited horses he was handling scarcely came to a halt before Howe had sprung from the truck." He banged on the door of the house next door and rushed upstairs to a window. He stretched his body across the gap between the buildings to reach Max Henshel, "who was at the window of the burning house begging for help."

Fireman Pearl held Howe's legs so he would not tumble down the gap between the buildings. Henshel was safely pulled through the window. Next came August Lang. And then Frederic Schmidt appeared. Behind him smoke and flames were enveloping the room and the Tribune said "he was desperate."

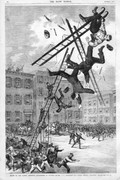

"Before Fireman Howe could get himself properly balanced to reach for the imperiled waiter, the latter sprang from the window ledge and threw his arms around the fireman's neck. The man's weight dragged Howe from the window-ledge, and it seemed certain that both men would be dashed to death on the pavement."

But Howe held on, and Pearl, still clutching his legs, "reached out and, by an almost superhuman effort, succeeded in drawing Schmidt through the window. He then helped Howe in."

In the meantime the other members of Hook and Ladder 7 were busy rescuing other residents. Steward Bergmann was stuck on the roof of the rear extension with his wife and child. They were carried down on a ladder by firemen. Two other occupants, a man and a woman, had jumped to the roof of the porch. Adelaide Junker suffered a sprained ankle; but both were carried down by fire fighters.

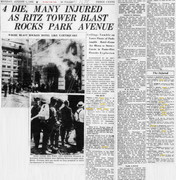

Hook and Ladder 7 responded to one of New York's greatest disasters in the early 20th century--the January 27, 1902 dynamite explosion being used in the construction of the subway on Park Avenue. Hundreds were injured, several killed and damage to buildings extended for blocks.

Fireman James Francis Kiernan found construction foreman Tubbs in the ruins. As he carried the man out, a second explosion occurred. The Evening World reported "The young fireman's arm was broken and he was blown four feet into the air, but he kept his head and got Tubbs safely out of danger."

Amazingly, according to the newspaper, this was just one of "a dozen escapes from death and [he] has saved a great number of lives." His cat-like defiance of death earned him the nickname "Lucky Jim."

The Evening World deemed Kiernan's luck complete in landing a pretty wife. September 29, 1902 (copyright expired)

Later that year the same newspaper reported on his upcoming wedding, saying his luck continued in managing to win the hand of Kathryn Rose Tynan. Kathryn, explained the newspaper, worked in a 23rd Street department store "and has such a reputation for beauty that she has attracted general attention among patrons of the store."

Press coverage routinely lauded Hook and Ladder 7 for its heroism and expertise. But that was not the case on February 22, 1903. A storm had covered the city streets in deep snow. Clearing the roads was, obviously, much more labor intensive than today. On the 21st when the firefighters were called to a blaze, only the avenues had been cleared.

The company's truck was pulled by three powerful horses, but they labored through the deep snow, becoming stuck several times on East 47th Street. The New-York Tribune reported that they "were badly used up" when they once again got stuck just before reaching Third Avenue.

The driver's solution was to whip them "furiously." When the horses still could not pull the truck from the snow, he climbed down "and lashed them from the front." The newspaper said "The lashing of the horses caused a crowd to gather, and several women and men expostulated with the firemen. They paid no attention, however, but continued to lash the rearing animals."

By coincidence, the Fire Department's chief veterinarian, Chief Shea, was heading downtown on the Second Avenue streetcar and saw what was going on. He ordered the men to stop, "and then patted and petted the animals until they recovered their good nature."

He then put the firemen to work. "They used their utmost strength to start the heavy truck, and succeed[ed] in doing so."

The company's truck was pulled by three powerful and handsome horses. The elevated train tracks in the background are, possibly, the Third Avenue el. photo via old-picture.com

It would not be many years, however before the horses were gone and Hook and Ladder 7 received its "Automobile Hook and Ladder Truck." Then in the spring of 1915 the fire department would have to replace it.

On February 17 that year Fireman Harry Flynn was driving the truck "at full speed" down Second Avenue to a fire on 19th Street. A streetcar driver, hearing the sirens, panicked and stopped short. To avoid a collision Flynn swerved and disaster followed.

The Evening World reported "The rear wheel of the big truck struck an elevate railroad pillar. The wheel was slewed around so that the axle was parallel with the body of the truck. Flynn was hurled to the ground, but was not hurt." It was the end of the shiny fire equipment. "The truck was put out of commission."

The year 1920 exemplified the heroics and the dangers of the job. On February 3 the men responded to a tenement fire on Fourth Avenue. Fireman Thomas Costigan found Agnes Butcher unconscious on the fourth floor and carried her to safety; and James Tubridy "forced his way" into the rear of the building to rescue "two hysterical girls," as described by The New York Herald.

A week later the company rushed to a fire in the Oliver Film Company on February 7. Motion picture film was made of celluloid, a highly flammable material that burned quickly and produced an extremely hot flame. When burned it produced poisonous gases and toxic smoke. Fireman James McMahon was overcome and was carried unconscious from the second floor.

And the following month, on March 8, the men faced an especially tricky blaze. Fire broke out in a middle car of a 10-car train on the Third Avenue Elevated. An aerial ladder was extended to the fire, but the men could not pour water on it until the electricity to the tracks was turned off. In the meantime residents, whose homes were mere feet from the tracks, worried that the delay would allow fire to spread.

Like most fire companies, Hook and Ladder 7 had a mascot. And theirs in 1937 was iconic--a black-spotted Dalmatian named Smoky. The New York Times noted on April 21 "Smoky, who is 3 years old, rides to fires on his company's truck and recognizes his company's alarm signal, jumping to his station like a veteran, according to his master, Fireman Robert Riley."

But on April 20 that year Smoky embarked on an adventure. He strolled out of the firehouse and headed east to Madison Avenue. Apparently the headquarters of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals looked inviting, so he dropped in.

The Times reported he "made himself at home in the lobby." He stayed there until officials tracked down his owners through his license tag. Society agent Tom McQuade then "escorted him home."

Members of the company would continue to receive commendation for their service throughout the decades. In 1951 Fireman Jacob H. Soffel, for instance, was awarded a medal for bravery.

Rather surprisingly, given the small scale and age of the building, Hook and Ladder Company 7 continued on in the 1893 firehouse until August 6, 1968, when it moved in with Engine Company 16 at No. 234 East 29th Street.

The firehouse was converted to photo studios and offices on the first and second floors, with a single-family duplex above. Then, in 1995, it was converted as the New York City Center of the Self Realization Fellowship, a religious movement founded by Paramahansa Yogananda, the author of Autobiography of a Yogi.

In renovating the structure, the group preserved LeBrun's stately exterior, so that it appears generally little changed from when Hook and Ladder Company 7 proudly moved back into its updated home in 1893.

- http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2017/08/napoleon-le-bruns-hook-ladder-no-7-217.html