Engine 264/Engine 328/Ladder 134 (continued)

Landmarks Preservation Commission:

DESIGNATION REPORT Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/ Ladder Company 134

Landmarks Preservation Commission

Designation Report Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/ Ladder Company 134

May 29, 2018

Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134

Built: 1910-12 Architect: Hoppin & Koen

Landmark Site: Borough of Queens, Tax Map Block 15559, Lot 25 in part, consisting of the portion of the lot east of the western facade of the building, as illustrated in the attached map.

On April 24, 2018, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/ Ladder Company 134, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 1). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were two speakers in favor of designation including representatives of Councilmember Donovan Richards, Jr. and the Historic Districts Council. There were no speakers in opposition. The Fire Department sent correspondence indicating their support for designation.

The Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134 firehouse at 16-15 Central Avenue was built in 1910-12 to serve the growing population of Far Rockaway, Queens. Designed by the architecture firm of Hoppin & Koen, the building is an excellent example of early-20th- century Renaissance Revival style civic architecture. The firehouse was built during a period of intense municipal building construction in the decades following the consolidation of the five boroughs in 1898. This particular firehouse was built to respond to increased development on the Rockaway Peninsula thanks to improvements in transportation that provided greater access to the area from the mainland.

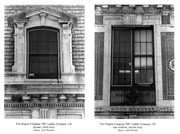

This three-story, Renaissance-inspired structure was a standardized design used at 18 different locations, ?simple and dignified and without any unnecessary elaboration,? and designed in versions with one, two, or three bays to adapt to varied urban sites. The prototype was designed by prominent architects Frances L.V. Hoppin & Terence A. Koen, partners who had earlier worked in the preeminent New York City firm of McKim, Mead & White. Originally, these firehouses were to be of fireproof concrete construction with a stucco finish. After bids for their construction overran the appropriated funds, cost savings were achieved by substituting red brick, limestone, and cast-stone cladding. The Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134 firehouse was one of three that were carried out with the larger, 3-bay facades. It features rusticated limestone at the ground floor, three segmental-arched vehicle bays, red brick cladding on the upper stories, and pairs of monumental brick pilasters supporting a cast stone entablature and brick parapet.

According to the Brooklyn Eagle, the greatest celebration in the history of the Rockaways was held in honor of the opening of this firehouse. Locally, it is affectionately called ?The Big House.? The Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134 firehouse serves as a reminder of the period of growth and promise in the years after the consolidation of New York City.

Description

Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134 at 16-15 Central Avenue, was erected in 1910-12 in the Renaissance Revival style. The building has a 70-foot-wide fa?ade on the south side of Central Avenue between Mott Avenue and Foam Place. The three-story building features a ground story clad in rusticated limestone with segmental arched vehicle bays, while the upper stories are clad in red brick laid in Flemish bond and flanked by pilasters supporting a cast-stone entablature and brick parapet. The FDNY seal occurs in the central spandrel panel above the second story.

Primary Central Avenue (North) Fa?ade

The three-bay-wide three-story Renaissance Revival style building features rusticated limestone at the first story above a granite water table. The segmental-arched vehicle bays have radiating voussoirs and scrolled keystones. There are metal bollards attached to each side of the vehicle entrances. The first story is topped by a wide limestone band (with attached bronze lettering), the upper part of which serves as a sill course for the second-story windows and the molded limestone bases of the double-height brick pilasters, which are topped by molded cast-stone capitals. Windows, grouped in sets of three, fill each of the three bays at the second and third stories. Within each bay, the windows are flanked by brick columns topped by molded cast-stone capitals. Metal flagpoles are attached to the two center pilasters at the second story. Soldier-coursed bricks top the windows and columns within each bay. Spandrel panels between the second and third stories are defined by soldier courses, stacked brick, and cast-stone corner blocks. The center spandrel has a cast-stone rondel with the seal of the Fire Department of New York, outlined with radiating brick. The building is topped by a cast-stone cornice, decorated with metopes, guttae, and dentils, below a brick parapet with a shallow center gable and stone coping blocks.

Alterations: Replacement doors with ?The Big House? painted on their non-historic wood lintels; replacement sash; non-historic lighting flanking the entryways and attached to the band above the first story; fall-out shelter sign; some dentils missing at the cornice; painted parapet

Secondary West Elevation The brick wall facing the parking lot to the west has stone coping blocks at the roofline and a first story entryway.

Alterations: brick covered with red paint; replacement door at first story entryway; security lamps; electrical conduits; louvered vent

Secondary East Elevation Partially visible brick wall facing adjacent building has stone coping blocks at the roofline.

Alterations: brick covered with red paint

Firefighting in New York City, Queens County and Far Rockaway

From the earliest colonial period, the government of New York took the possibility of fire very seriously. Under Dutch rule all men were expected to participate in firefighting activities. After the English took over, the Common Council organized a force of thirty volunteer firefighters in 1737. They operated two Newsham hand pumpers that had recently been imported from London. By 1798, when New York City consisted of all of Manhattan and part of the south Bronx, the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), under the supervision of a chief engineer and six subordinates was officially established by an act of the state legislature. Volunteer firefighting persisted in rural areas outside of the city proper, including all of Queens County, which consisted of Long Island City, Newtown, Flushing, Jamaica, and three towns in what is now Nassau County. The earliest documented company was the Wandownock Fire, Hook & Ladder 1, founded in Newtown (now Corona and Elmhurst) in 1843. Equipped with a single, hand-drawn firefighting apparatus, the company was housed in a modest frame building located on public land.

In May 1865, the New York State Legislature established the Metropolitan Fire District, comprising the cities of New York (south of 86th Street) and Brooklyn. The act abolished the volunteer system in these areas and created the Metropolitan Fire Department, a paid professional force under the jurisdiction of the state government. A military model was adopted for the firefighters, which involved the use of specialization, discipline, and merit. By 1870, regular service was extended to the ?suburban districts? north of 86th Street and expanded still farther north after the annexation of parts of the Bronx in 1874. New techniques and equipment, including taller ladders and stronger steam engines, increased the department?s efficiency, as did the establishment, in 1883, of a training academy for personnel. The growth of the city during this period placed severe demands on the fire department to provide services, and in response the department undertook an ambitious building campaign.

The area served by the FDNY nearly doubled after consolidation in 1898, when the departments in Brooklyn and numerous communities in Queens and Staten Island were incorporated into the city. After the turn of the century, the Fire Department acquired more modern apparatus and motorized vehicles, reflecting the need for faster response to fires in taller buildings.

By the time of the Consolidation of Greater New York of the City in 1898, more than two thousand volunteer firemen were active in Queens. Public officials vowed to expand professional fire service throughout the new borough. The Greater New York Charter proclaimed: ?The paid fire department shall, as soon as practical, be extended over the Boroughs of Queens and Richmond . . . there upon the present volunteer fire departments now maintained therein shall be disbanded.? Long Island City was the first community to benefit, where the architect Bradford Gilbert's Dutch Renaissance Revival-style firehouse for Engine Company 258, a New York City landmark located at 10-40 47th Avenue, was completed in 1903. While a total of fifty-nine firehouses were built city-wide over the subsequent decade, the majority of Queens? communities remained without municipal fire protection. In 1910, the City embarked on a program to construct new firehouses in underserved areas of the city, including Far Rockaway, a growing seaside community that was still being served by a fire house built for use by the volunteer department.

Firehouse Design in New York City and the Boroughs

Beginning in the 1850s, there was an increasing desire for symbolic architectural expression in municipal services buildings, such as police stations and firehouses. The 1854 Fireman?s Hall, 153 Mercer Street, with its highly symbolic ornamentation, reflected this new approach, using flambeaux, hooks, ladders, and trumpets for its ornament. In 1880, Napoleon LeBrun & Son was appointed to serve as the official architectural firm for New York?s Fire Department, remaining in that position until 1895. During that time, the firm designed 42 firehouses for the city in a massive effort to modernize its fire facilities and to accommodate the growing population of the city. Although the firm?s earliest designs were relatively simple, later buildings were more distinguished and more clearly identifiable as firehouses. While the basic function and requirements of the firehouse were established early in its history, LeBrun is credited with standardizing the program, and introducing some minor, but important, innovations in the plan. Placing the horse stalls in the main part of the ground floor to reduce the time needed for hitching horses to the apparatus was one such innovation.

Firehouses were usually located on midblock sites because these were less expensive than more prominent corner sites. Since the sites were narrow, firehouses tended to be three stories tall, with the apparatus on the ground story and rooms for the company, including dormitory, kitchen and captain?s office, above.

After 1895, the department commissioned a number of well-known architects to design firehouses. Influenced by the Classical Revival which was highly popular throughout the country, New York firms such as Hoppin & Koen, Flagg & Chambers, Horgan & Slattery, and Robert D. Kohn created facades with bold Classically-styled designs. Government buildings were placed in neighborhoods throughout the city, with the intention of inspiring civic pride in the work of the government and the country as a whole. Buildings such as these fire houses are easily recognizable and announce themselves as distinct from private structures, using quality materials, workmanship and details to create buildings of lasting beauty and significance to their localities.

Prior to becoming part of the City of New York in 1898, the area that now forms Queens County included one city, Long Island City, which was served by a paid fire department. The six, mostly-rural towns that joined Long Island City to create the modern borough were served by 15 volunteer fire departments. These departments usually occupied small wooden structures that were lacking in up-to-date facilities that were needed by their communities as they grew and were absorbed by the new metropolis.

In 1910, the Fire Department, under the leadership of Commissioner Rhinelander Waldo, unveiled a new uniform type ?Model Fire House,? plans and specifications for which were prepared by architects Hoppin & Koen. Intended for construction in 1911 in 20 locations ? 11 for new companies and nine to replace dilapidated buildings, only 18 were ultimately built, including Engine Company 264 in Far Rockaway. These structures were to be absolutely fireproof. Budgeting some $500,000 for the whole group, the FDNY anticipated significant cost advantages through building materials purchased at wholesale and builders bidding on one entire contract, and expected savings on building maintenance. This uniform concept would also provide flexibility, allowing for firehouses ranging from one to three bays. According to Fire Department records, ?The new houses are to be of uniform type. They are to be built of reinforced concrete with metal doors and trimmings. All wood is to be eliminated. This will not only make them absolutely fireproof, but reduce materially the cost of maintenance through deterioration.? The Real Estate Record & Builders Guide called the neo-Classical style design ?simple and dignified and without any unnecessary elaboration.? However, construction of these firehouses was delayed by opposition from building interests that felt threatened by the new technology. Stone cutters, brick layers, and various manufacturers mounted a successful campaign to stop the plan, demonstrating that the final costs would be prohibitively higher than traditional methods. Red brick and limestone cladding was substituted, saving an estimated $168,000, and as a result, the Classical design of these firehouses was executed in traditional materials.

Far Rockaway

Far Rockaway is New York City?s easternmost community on the Rockaway Peninsula, a four-mile-long barrier beach sandwiched between Jamaica Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Bordered by the Edgemere neighborhood on its west, Far Rockaway adjoins the town of Lawrence in Nassau County on its east. Before Europeans made contact with Native Americans on Long Island, present-day Rockaway and its vicinity were occupied by bands of Eastern Algonquian people known as the Rockaway and the Canarsie. ?Rockaway? has been translated as ?sandy place? or ?place of our people,? and although Captain John Palmer ?purchased? the peninsula from Native chiefs in 1685, several large shell banks marking indigenous gathering places remained through the 19th century. In 1918, historian Alfred H. Bellot noted that one of these banks, at Bayswater, ?must have contained many thousand tons of clam shells,? which, by that time, had been ?carted away and used for filling in purposes and road making.?

The title to the entire Rockaway Peninsula derives from John Palmer?s patent. In 1687, Palmer and his wife Sarah sold the land to Richard Cornell, an ironmaster from Flushing. Cornell and his family are believed to have been the peninsula?s first white settlers, constructing a house in present-day Far Rockaway in 1690; their household included at least three enslaved African-Americans. In 1830, John Leake Norton purchased a portion of the Cornell Estate, and three years later, he organized the Rockaway Association, which counted dozens of prominent New Yorkers among its members. The Association soon demolished the old Cornell house and constructed, in its place, the Rockaways? first commercial hotel?the Marine Pavilion?as well as a new stagecoach route called the Jamaica and Rockaway Turnpike. Over its three decades in business, the Marine Pavilion ?attracted attention to the Rockaways throughout the Union,? establishing the peninsula?s reputation as a fashionable seaside resort and spurring the construction of several other hotels there.

Improved transportation fueled Far Rockaway?s subsequent development as both a summer resort and year-round community. In 1869, the South Side Railroad completed a line between Valley Stream and Far Rockaway, and by 1873, a competing line, operated by the Long Island Rail Road, linked it with Jamaica. In 1880, the New York Woodhaven, and Rockaway Railroad completed a trestle over Jamaica Bay, providing access from the mainland to the middle of the peninsula. Horsecar service was established between Far Rockaway?s train station and beach in 1886, and in 1888, the community was incorporated as a village within the town of Hempstead. Over the following decade, Far Rockaway acquired many of the trappings of a permanent community, including gas, water, and telephone service, sewers, curbed and paved streets, a permanent postmaster, and its own bank and newspaper.

Far Rockaway?s growth continued after 1898 when it joined the City of New York, forming, along with Rockaway Beach and Arverne-by-the-Sea, the Fifth Ward of the Borough of Queens. That year, Brooklyn Rapid Transit trains began providing summer service over the Rockaway trestle, and the subsequent electrification of this line and inauguration of direct service between the Rockaways and Manhattan in 1910 attracted many commuters. Its popularity as a seaside resort continued during this time with Far Rockaway?s largest resort, the Ostend Beach, opening in 1908. Summer steamships continued to serve the community from various points across New York City, including Manhattan, Sheepshead Bay, and Coney Island.

By 1918, the community numbered around 11,000, according to Bellot, and included ?four churches, two synagogues, a splendidly equipped ? hospital ? ; two banks; three newspapers; many spacious and elaborate hotels; a cable terminal where the Atlantic cables reach the shores of America,? as well as numerous golf, yacht, and tennis clubs, movie theaters, and ?splendid stores.? The post-World War I housing crisis, which led many bungalow owners to winterize their homes, increased the community?s year-round population, as did planned improvements including the construction of the Rockaway boardwalk and the Cross Bay Bridge for automobiles. These may have been initiated, at least in part, in response to a robust local secession movement, which was fueled by a perceived lack of city resources among Far Rockaway residents. By 1925, according to one contemporary account, the neighborhood was experiencing a ?real estate boom which ? outclasses Florida?s palmiest days.?

Far Rockaway remained a popular seaside destination until after World War II, when increasing prosperity, widespread automobile ownership, and the rise of air travel led to the decline of many of the region?s old resort areas. Although Far Rockaway became increasingly accessible with the extension of the IND Subway to the peninsula in 1956, urban renewal drastically changed the community, leading to large-scale clearance, the construction of high-rise apartment buildings along the beach, and the displacement of many families to other neighborhoods or into substandard housing in the Rockaways. Today, Far Rockaway is a diverse neighborhood with large white, African-American, and Latino populations and a substantial Orthodox Jewish community. Its growing population includes immigrants who have settled there since the 1980s from countries including Afghanistan, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, and Jamaica.

Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134

The Far Rockaway Volunteer Fire Department was organized on January 26, 1887 and was absorbed by the New York Fire Department and professionalized on September 1, 1905, becoming Engine Company 164. The new company continued occupying the old volunteer firehouse, but Far Rockaway residents were soon up in arms over the lack of adequate fire protection for the rapidly growing community. In 1910, the Fire Commissioner announced that $50,000 was appropriated for a new firehouse to be built at the same location as the old wood-frame building on Central Avenue. The site, a large rectangular lot with a wide frontage facing Central Avenue at Mott Avenue, also contained a court house, since demolished, and a library, which was replaced by a new library building in the 1960s. The intersection of Central and Mott Avenues and the surrounding streets was Far Rockaway?s civic center in the early-20th century, and included churches, schools, and a railroad station. It remains the community?s main commercial district. Hoppin & Koen filed plans for the Far Rockaway firehouse in 1911 at an estimated cost of $67,500, although the department had authorized only $50,000 for the building. The construction firm of Cockerill & Little won the contract at the lowest bid of $65,769. The final cost reported in 1913 was $67,514. This was one of three Hoppin & Koen modular firehouses that were carried out with the wider, three-bay fa?ade, and the least expensive of the three to build. Upon the building?s completion in 1912, the fire company?s name was changed to Engine Company 264. The firehouse, which then became the fire headquarters for all of the Rockaways, also included a telegraph bureau. According to the Brooklyn Eagle, the greatest celebration in the history of the Rockaways was held in honor of the opening of this firehouse. The following year, Hook & Ladder Company134 was organized in the same building, and in 1939, Engine Company 328 was established at the same location. The full name of the firehouse then became Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134, and remains so today. Over the years, the firefighters of Engine Companies 264 & 328/ Ladder Company 134. Known as ?The Big House,? have responded to fires and emergencies both big and small in Far Rockaway and throughout the Rockaways. Most notably, its members performed heroically during a series of large hotel fires in the mid-to-late 20th century, savings lives and minimizing damage to properties and the surrounding community.

Hoppin & Koen, Architects

Francis Laurens Vinton Hoppin (1866-1941) was born in Providence, Rhode Island the son of Washington Hoppin, a prominent physician and caricaturist, and Louise Claire (Vinton) Hoppin. He received his early education in the Providence public schools, later transferring to the Trinity Military Institute in upstate New York. He attended Brown University and studied architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1884-1886 before traveling to Paris to further his studies at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. He returned to the United States and worked in his brother?s Providence firm, Hoppin, Read & Hoppin in 1890-91 before moving to New York where he joined the firm of McKim, Mead & White as a draftsman. There he met Terence A. Koen (1858-1923), a fellow draftsman, who had joined the firm in 1880.

In 1894 Hoppin and Koen formed a partnership and went into practice for themselves. The firm was responsible for designing the Fire Company No. 65 at 33 West 43rd (1897-98) and former New York Police Headquarters at 240 Centre Street (1909), both designated New York City Landmarks, as well as numerous townhouses including the individually designated James F. D. and Harriet Lanier House at 123 East 35th Street (1901-03, a designated New York City Landmark), and several country estates on Long Island, New Jersey and Massachusetts including ?The Mount? for the author Edith Wharton in Lenox, Massachusetts. Shortly after Koen died in 1923, Hoppin retired and devoted himself to painting.

Conclusion

Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/ Ladder Company 134 firehouse, designed by the prominent architecture firm of Hoppin & Koen, is an outstanding example of early twentieth century, Renaissance Revival style civic architecture. The three-story, classically-inspired structure, one of 18 based on a standardized modular design, was one of only three carried out with a wider, three-bay facade. According to the Brooklyn Eagle, ?the greatest celebration in the history of the Rockaways? was held in honor of the opening of this firehouse. Locally, the firehouse is affectionately called ?The Big House.? Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134 serves as a reminder of the period of growth and promise in the years after the consolidation of New York City.

(Report researched and written by Donald Presa, Michael Caratzas, Research Department)

Findings and Designation Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134

On the basis of a careful consideration of the history, the architecture, and other features of this building, the Landmarks Preservation Commission finds Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134 has a special character and a special historical and aesthetic interest and value as part of the development, heritage, and cultural characteristics of New York City. The Commission further finds that Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134 firehouse was designed by the prominent architecture firm of Hoppin & Koen; that the building is an outstanding example of early twentieth century, Renaissance Revival style civic architecture; that it was built to respond to increased development on the Rockaway Peninsula thanks to improvements in transportation that provided greater access to the area from the mainland; that the threestory, Renaissance-inspired structure was a standardized design used at 18 different locations; that this was one of three that were carried out with the larger, 3-bay facades; that its architects, Frances L.V. Hoppin and Terence A. Koen, had earlier worked in the preeminent New York City firm of McKim, Mead & White; that according to the Brooklyn Eagle, ?the greatest celebration in the history of the Rockaways? was held in honor of the opening of this firehouse; that locally, the firehouse is affectionately called ?The Big House;? and that Firehouse, Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134 serves as a reminder of the period of growth and promise in the years after the consolidation of New York City. Accordingly, pursuant to the provisions of Chapter 74, Section 3020 of the Charter of the City of New York and Chapter 3 of Title 25 of the Administrative Code of the City of New York, the Landmarks Preservation Commission designates as a Landmark Firehouse Engine Companies 264 & 328/Ladder Company 134, 16-15 Central Avenue, Queens, and designates as its Landmark Site Borough of Queens Tax Map Block 15559, Lot 25 in part, consisting of the portion of the lot east of the western facade of the building, as illustrated in the attached map.

(Meenakshi Srinivasan, Chair)

http://www.neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb_files/2018-Firehouse--Engine-Companies-264-238.pdf

https://newyorkhistoryblog.org/2018/06/far-rockaway-fire-house-police-station-historic-buildings/